The Polar Vortex may make simple tasks like getting to work a lot more difficult, but new research suggests that exposure to cold weather might in fact make it easier to lose weight.

In a paper published Wednesday in the journal Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, Dutch researchers posit that regular exposure to mild cold may spur weight loss by triggering one of the body’s heat-generating methods.

As humans shiver in response to cold, the researchers explain, the body ramps up heat production, which in turn increases the amount of energy it uses. However, exposure to mild cold, it appears, can trigger “nonshivering thermogenesis,” or heat production that is stimulated not by shivering, but by brown fat cells.

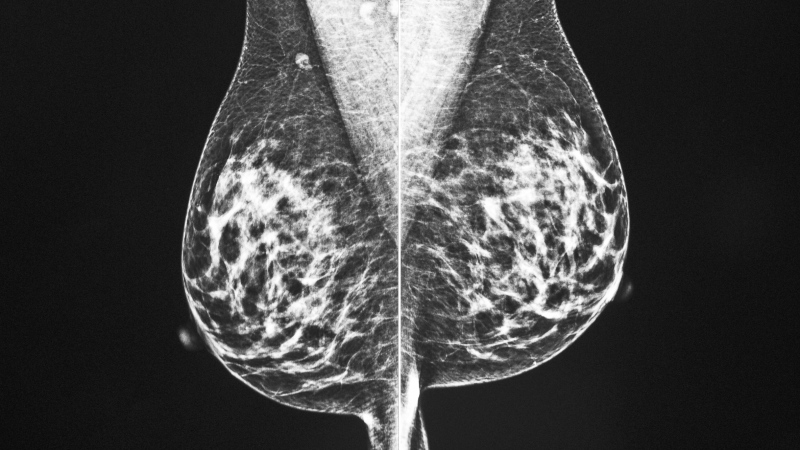

The primary function of brown fat cells is to generate body heat in mammals that do not shiver, particularly newborn babies and hibernating animals. Unlike white fat cells, brown cells do not store energy, using it instead to heat the body. They are called brown cells because of the darker colour of their mitochondria, the source of their heat-generating energy.

Other research suggests that in addition to using their own energy, brown fat cells recruit energy from white fat cells, which further aids weight loss.

While young adults and the elderly show a drop in nonshivering thermogenesis (NST) in response to mild cold, most young people and middle-aged adults experience as much as a 30 per cent spike in NST when exposed to mild cold.

“Thus, NST can have a physiologically significant effect upon energy expenditure and can potentially affect our energy balance,” the researchers write.

Indeed, the researchers cite a study conducted in Japan that found a “significant decrease” in body fat after study subjects were exposed to temperatures of 17 C for two hours a day over six weeks. The weight loss appeared linked to how much brown fat the subjects had.

The Dutch researchers added that in a separate study, they observed that shivering and overall discomfort decreased in subjects they exposed to temperatures of 15 C for six hours per day over ten days.

The researchers note that over time, changes in living conditions, particularly in Western countries, have had considerable impacts on human health.

“For example, we are much better able to control our ambient temperature. Consequently, we cool and heat our dwellings for maximal comfort while minimizing our body energy expenditure necessary to control body temperature.”

The researchers say that because we now spend about 90 per cent of our time indoors, some research should be focused on the health effects of regulated ambient temperatures.

The researchers note that while weight loss can often be achieved by simply eating less and exercising more, maintaining weight loss can be difficult. And with more than 500 million people worldwide now either overweight or obese, which increases the risk of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some forms of cancer, it is imperative that researchers find new ways to stimulate weight loss.

So, they write, “similarly to exercise training, we advocate temperature training.” They note that as people exercise to boost their physical fitness and lower their risk of developing disease, so too should they expose themselves to more varying temperatures in order to stimulate the body’s ability to generate heat and expend energy.

Buildings are climate-controlled to “minimize the percentage of people who are dissatisfied,” which results in relatively high indoor temperatures during the winter, they write.

That lack of exposure to varied temperatures, they say, leaves people at risk of developing obesity.

They also note that a lack of exposure to varied temperatures makes people, particularly the elderly, less able to adapt to cold snaps, which can increase the risk of death from ailments such as cardiovascular disease or pulmonary disease.

“Therefore, in parallel to physical exercise, one should promote temperature training as part of a healthy lifestyle,” the researchers conclude.