Phthalates -- chemical compounds frequently used in plastic packaging materials, personal care products, detergents and other household items -- could considerably increase the risk of allergies, including asthma, in children exposed during pregnancy and breastfeeding, new research shows.

Phthalates, which are identified as endocrine disruptors for their disruptive effect on hormones, may also affect the immune system by increasing allergy risk in children exposed to the substances via their mother during pregnancy or breastfeeding, according to research from Germany's Helmholtz Centre For Environmental Research (UFZ) in conjunction with scientists from the University of Leipzig and the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ).

The study, based on a cohort of 629 mother-child pairs, established a significant link between higher concentrations of the metabolite of benzylbutylphthalate (BBP) in the mother's urine and the presence of allergic asthma in their children.

The scientists then confirmed the results in mice, by exposing them to a phthalate concentration during pregnancy and lactation, which led to comparable concentrations of the BBP metabolite in urine to those observed in heavily exposed mothers from the human cohort.

The mice's offspring displayed a clear tendency to develop allergic asthma, and the effects were even passed on to the third generation, the study reports.

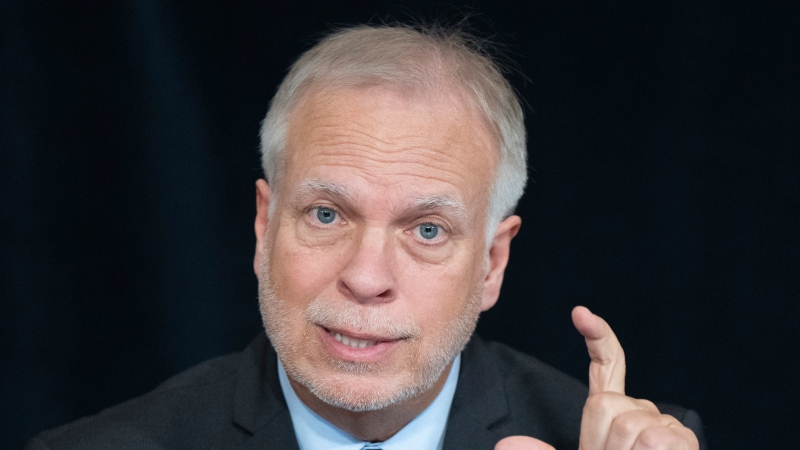

However, there was no increase in allergic symptoms in adult mice, which suggests that time is a decisive factor in their development. "If the organism is exposed to phthalates during the early stages of development, this may have effects on the risk of illness for the two subsequent generations," explains Dr. Tobias Polte from UFZ.

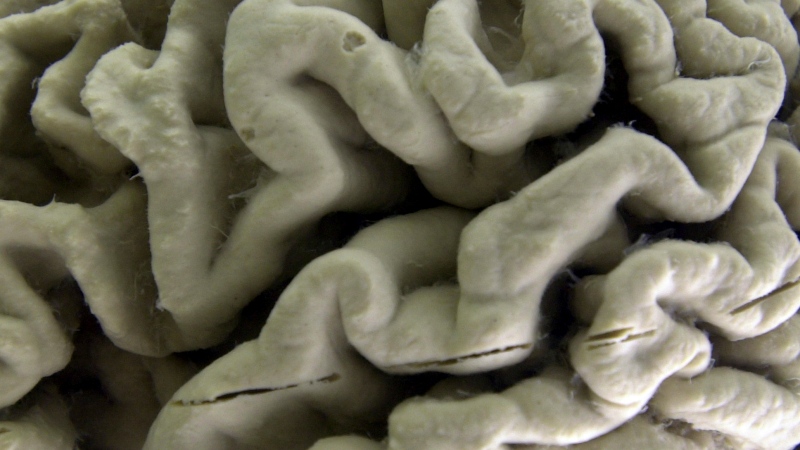

According to the study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, phthalates cause epigenetic modification of the DNA via DNA methylation, by which methyl groups attach themselves to genes, effectively "switching off" decisive genes that contribute to inhibiting the development of allergies.

In mice, the researchers were able to establish that a repressor gene switched off due to DNA methylation was responsible for the development of allergic asthma. When looking at asthmatic children in the cohort, they again found that the gene was blocked by methyl groups and thus could not be read.

Despite a wealth of research in the field, one of the major challenges researchers now face is to determine the exact action of these chemical substances, which have also been linked to infertility and the early onset of puberty.