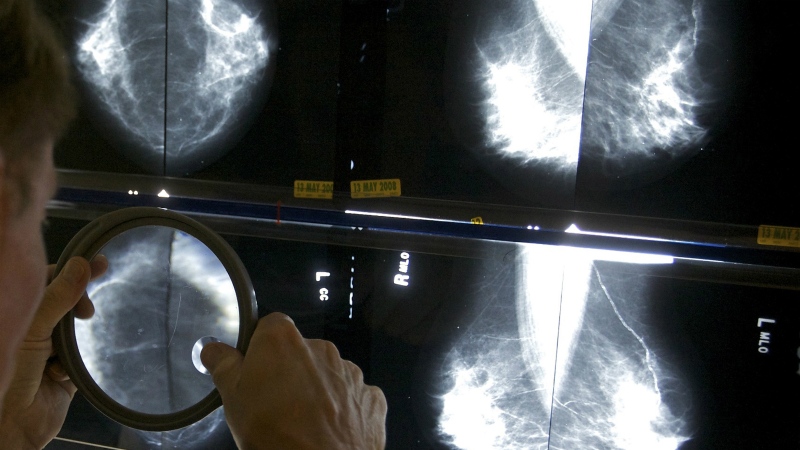

Another study is suggesting that low-sodium diets may not be of much help to people who don’t have high blood pressure, and might even be linked to an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes.

The study comes from researchers at McMaster University’s Population Health Research Institute. Members of the team have conducted similar studies in the past, including one in 2011 and one in 2014.

This time, the team pooled together even more data from four studies involving more than 130,000 people from 49 countries, in a study they say is the largest yet to look at the relationship between sodium intake and heart events.

The team looked at urine levels of sodium in the study participants, their blood pressure status, and whether they experienced a “cardiovascular event,” such as a heart attack or stroke over the next four years.

About half the group had high blood pressure, or hypertension, and the other half didn’t.

The mean age of those with hypertension was 58, while it was 50 in those without hypertension. Over the course of the study, more than 6,800 people with hypertension had a cardiovascular event, as did 3,000 in the normal blood pressure group.

The researchers found that those with hypertension who ate high sodium diets containing 6,000 mg of sodium or more indeed have an increased risk of heart events, such as heart attacks and strokes.

That finding was not surprising as plenty of research has drawn a link between high blood pressure, high sodium intake and higher risk of heart events.

But this study also found that in those with normal blood pressure, high sodium intake was not linked to heart events.

What’s more, researchers noticed a distinct link between heart events and a low sodium intake of 3,000 mg of sodium a day or less. The finding held in both those with high blood pressure and those without it.

In fact, the risk of a heart event for those with low sodium intake was almost as high for the entire group as a high sodium intake was on those with high blood pressure.

“These are extremely important findings for those who are suffering from high blood pressure,” Andrew Mente, lead author of the study, said in a press release.

Current Canadian guidelines recommend adults consume less than 2,300 mg of sodium per day—about the equivalent of one teaspoon or five millilitres of salt. Most Canadians consume much more than that, between 3,400 and 4,000 mg, on average.

The authors of the study suggest that drastic salt reduction should only be recommended to those with high blood pressure who also have a high daily sodium intake—not the general population.

“This argues against a population-wide approach to reduce sodium intake in most countries, except in those where the mean sodium intake is high (eg, some in central Asia or some parts of China),” they write.

The researchers say that for healthy people, lowering salt intake will only slightly improve blood pressure.

But more importantly, because very low sodium intake has unintended effects, such as adverse elevations of certain hormones and a significantly increased risk of heart disease and stroke, those risks outweigh any benefits of lowering sodium.

It’s important to note that the study was observational in nature, and thus was not designed to prove that low-sodium or high-sodium diets were the cause of the heart event.

“Despite careful design, follow-up, and analyses, observational analyses cannot definitively prove causality,” the authors write.

The researchers say the best way to test their findings about high and very-low-sodium diets would be to hold large and long-term randomized controlled trials. That would be the ideal way to guide public policy, they say.