A critical shortage in Canada of medications ranging from antibiotics to chemotherapy is now affecting some epilepsy patients, as drugs get pulled from the market often with little or no warning.

Responding to pressure from Ottawa, drug makers have just agreed to make information about impending national drug shortages available on two websites, the Saskatchewan Drug Information Services and Vendredi PM.

However, manufacturers have done little to address the actual shortages, which largely affect lower-cost generic drugs that have smaller profit margins.

According to a briefing note about anti-epileptic drug (AED) shortages by the Canadian Epilepsy Alliance, patients across the country are reporting that they can't access their medications.

Since 2009, there have been shortages of several anti-seizure drugs, including primidone, phenobarbital, ethosuximide, phenytoin and clobazam. All of the drugs except for phenytoin are generics.

"Sudden discontinuation of an AED is potentially life-threatening for someone with epilepsy," says the briefing note.

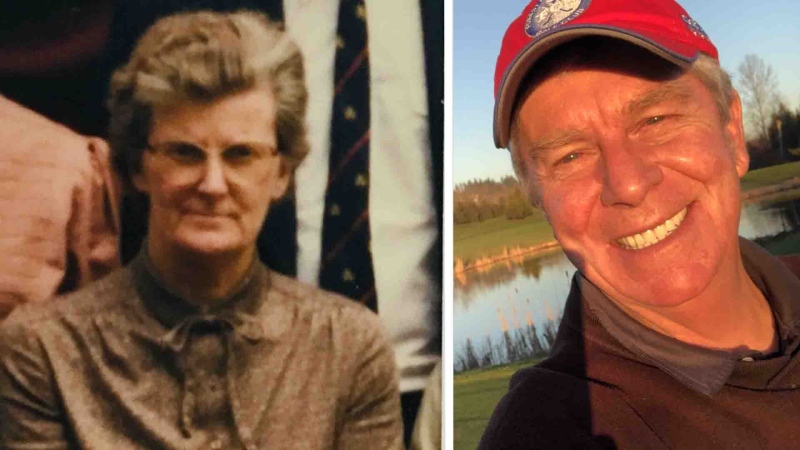

Robert Logan kept his epilepsy under control for 20 years with the help of medication, including primidone. When the drug maker stopped manufacturing primidone, his doctor switched him to another anti-seizure drug.

On the new medication, Logan, who also has cerebral palsy, suffered two grand mal seizures in quick succession and ended up in hospital, said his father, Dave.

"Whoever is responsible, they are paying with people's lives," Dave Logan told CTV News. "They are going to have cemeteries full, and the hospitals full."

Diane Sallows had a similar experience. Primidone kept her seizures under control for 60 years until July, when her nursing home ran out of the drug. She was forced to try phenobarbital, and within days she ended up in hospital with seizures.

"What is it going to take, someone to lose their life?" Dianne's sister Debbie Sallows told CTV. "So these drug companies have to supply patients' medications, or these patients have to be admitted to the hospital so they can receive their proper medications till these drug companies fill the right amount for long-term patients to stay alive."

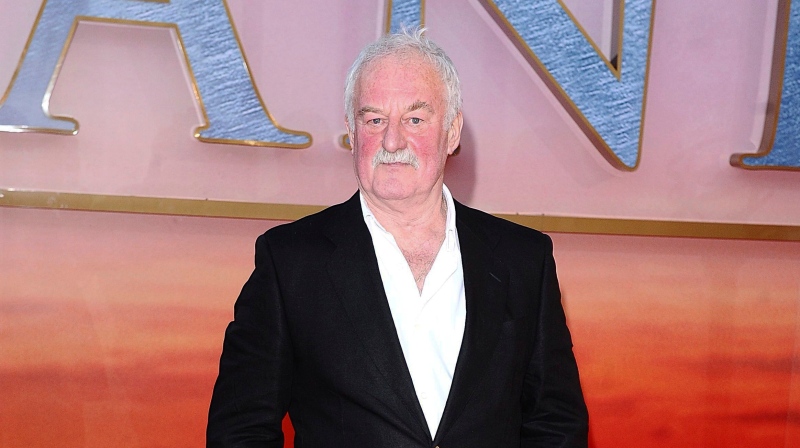

Doctors say the notifications don't address the actual problem: the drug shortages. Dr. Richard McLachlan of the London Health Sciences Centre in Ontario, says patients often have no warning, and are told by the pharmacist that the drug is no longer available when they try to fill a prescription.

"These are drugs that have been around for 50 years or more," McLachlan, who serves as an adviser to the Canadian Epilepsy Alliance, told CTV News. "Why all of a sudden they have these problems when they didn't before is a bit peculiar."

Until drug companies explain the shortages, doctors and patients are left looking for answers. The only clue is that a number of drugs that disappear from the shelves are generics, which cost less and have lower profit margins.

With a report from CTV's medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip