The federal government has pledged up to $750 million in compensation to Indigenous children who were taken from their families starting in the 1960s and placed into foster care or adopted into non-Indigenous families.

The ‘60s Scoop swept up tens of thousands of Indigenous babies and children across Canada and lasted up until 1985. The policy prompted lawsuits across the country, and in February, the Ontario Superior Court found that the government was liable for harm to the survivors.

On top of the $750 million in compensation, Ottawa has pledged $50 million for a healing foundation aimed at helping Indigenous families heal and $75 million for legal fees.

But some ‘60s Scoop survivors aren’t convinced that the federal government’s settlement goes far enough.

An isolated childhood

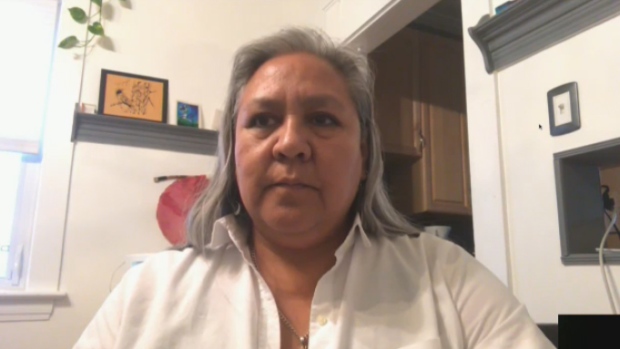

Raven Sinclair was four years old when she and her eight siblings were taken from their mother. It’s a day she remembers “like it was yesterday.”

They were all put into foster care, and some -- including Sinclair -- were adopted by non-Indigenous families. She spent her youth between Ontario, Saskatchewan and Germany. All the while, she knew nothing about her ancestry.

“I was raised to believe that I was Metis and French Metis. That’s the only information that my adoptive parents had. I have since found out that I am status Cree and Scottish,” she told CTV’s News Channel.

Sinclair recognizes that her adoptive home brought certain “material advantages,” but it came at a price.

“There wasn’t a day that went by that I didn’t experience racism, discrimination, bullying, ostracism,” she said. “I didn’t see another Indigenous person until I was about 15.”

Two of her brothers were paired in a home together, but Sinclair was placed alone. She said the lack of understanding of her past led to years feeling isolated.

Sinclair grew up to become a social work professor at the University of Regina, and her research involves exploring the stories of others swept up in the ’60s Scoop.

Sinclair spotted a common thread in those stories: many survivors grew up thinking they were alone in their experience.

“That’s so isolated we were. There’s 20,000, 30,000 of us who thought we were the only ones who this happened to. And the loss of family, community, culture, language -- there is no measure for it. It has altered our lives permanently and so many of us are struggling still.”

Researching those stories has convinced Sinclair that the federal government’s $750 million deal is “very low.”

“That settlement is based on an estimate of 20,000 survivors. So if that were divided up, it would amount to about $37,000 per survivor,” she said. “When I look at some of the stories that I’ve had the chance to witness, I’m not convinced that is an adequate compensation for those people.”

However, Sinclair says she is happy about the government’s $50 million commitment for a healing foundation.

“I think that programs and services and interventions to help people to deal with the psychological and emotional trauma of what happened to them and maybe to recover language and culture, those are really good things, and I think those will have a beneficial impact in the future.”

Living with a ‘crisis of identity’

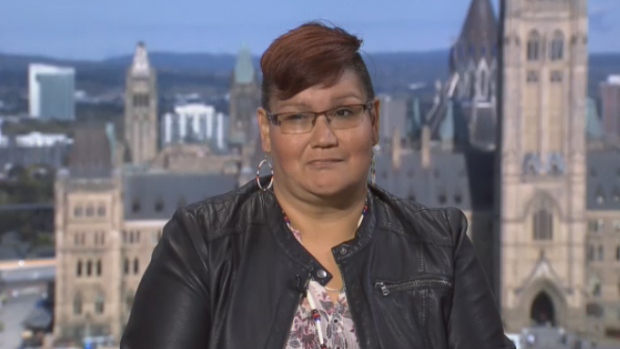

Colleen Cardinal was a baby when she and two older sisters were taken from her family in 1972, and placed in a non-Indigenous home in Ontario. Cardinal says that, after years of physical and sexual abuse, she ran away as a teenager.

“We were brought into a middle-class, upper-middle-class white home. We had lots of opportunities, but behind closed doors it was very traumatic for my sisters and I,” she said.

After she left, Cardinal was reunited with her parents. But she still lived with a “crisis of identity.”

“I spent probably most of my life trying to be white so I could fit in,” she said.

It wasn’t until she attended college, in 2002, that Cardinal first learned about the ‘60s Scoop and how many other Indigenous children were taken from their homes.

“When I found out there were over 20,000 other people out there like me, I wanted to find them,” she said.

She has since co-founded the National Indigenous Survivors of Child Welfare Network. Cardinal said she’s “a little bit disappointed” by the government’s $750 million announcement.

“I don’t know what amount of number would be adequate. You can’t buy back culture and wellness. But I would like to that think the crimes that have been committed against Indigenous children are worth a little bit more,” she said.

‘How do you measure the trauma?’

Margaret Murray, who goes by her spirit name Nakuset, was taken from her family in Saskatchewan as a child. She has since reunited with her mother – a survivor of the residential school system – but says that being with her biological family can be “stressful.”

“When I go to my community, everybody speaks Cree. So right away, there’s a language barrier,” she told CTV News Channel. “I don’t know really know how to live off the land. There are years and years and years of lost family moments.”

Now the executive director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal, Murray described Bennett’s announcement as “overwhelming” and said the federal government is now in the difficult position of deciding how much money survivors are entitled to.

“How do you measure the trauma? How do you measure how much people are going to be receiving for the abuse that they may or may not have endured … and also for losing your culture and your family and your language,” she said.

The most important step for moving forward, Murray said, is educating Canadians on what happened to those children.

“People need to know about how the history of government policies have impacted us and how we are trying to survive society today,” she said.

“People really don’t have a true understanding as to why some of us struggle.”

With files from The Canadian Press