Vancouver is the home to Canada's first-ever crackpipe vending machines, which were installed in the city’s troubled Downtown Eastside in a bid to curb the spread of disease among drug users.

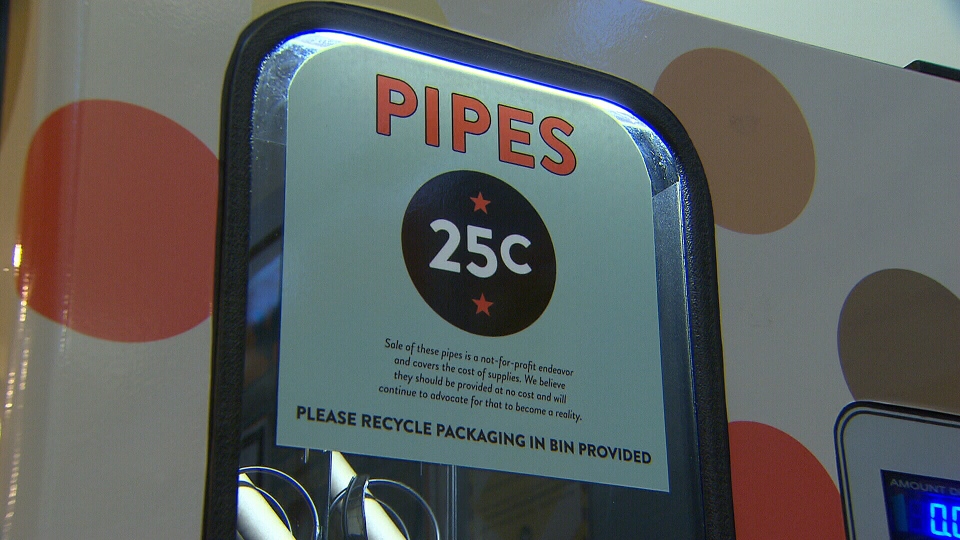

Portland Hotel Society's Drug Users Resource Centre operates two of the machines. They dispense Pyrex crackpipes for just 25 cents.

"For us, this was about increasing access to safer inhalation supplies in the Downtown Eastside,” Kailin See, director of the DURC, told CTV Vancouver.

She said the pipes are very durable and less likely to chip and cut drug users' mouths, which helps stop the spread communicable diseases including HIV and hepatitis C.

The vending machines are part of a harm-reduction strategy introduced by InSite, North America's only medically supervised safe injection site. InSite is located in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside which is considered Canada’s “poorest postal code.”

Like the vending machines, InSite has ignited a firestorm of controversy since first opening 10 years ago. As many as 800 people use the site each day.

The federal government tried to shut down InSite in 2008, but it survived thanks to a Supreme Court of Canada ruling that upheld the facility’s exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

In a statement sent to CTV News Saturday, Minister of Public Safety Steven Blaney said he disagrees with the initiative. The minister said he supports treatment that ends drug use, including “limiting access to drug paraphernalia” by youth.

“Drug use damages the health of individuals and the safety of our communities,” Blaney said. “We believe law enforcement should enforce the law.”

Health-care professionals say facilities like InSite save lives and reduce overdose deaths. Studies have shown that harm reduction strategies lead to a decrease in infectious disease rates, and addicts are more likely to get treatment since they're in regular contact with health professionals.

"This is one piece of the larger puzzle," See said. "You have to have treatment, you have to have detox, you have to have safe spaces to use your drug of choice, and you have to have safe and clean supplies."

She pointed out while the pipes cost $0.25, every new case of HIV or hepatitis could cost taxpayers up to $250,000 in medical treatment.

With files from CTV Vancouver