QUEBEC -- The mandate of the commission looking into corruption in Quebec's construction industry is being extended by 18 months, with untold political consequences.

The unpredictable consequences of dragging out the deadline for the final report to April 2015 are illustrated by a trickle of new revelations this week that have dented reputations at different levels of government, and in the private sector.

The original deadline for commission president France Charbonneau to table her report was October 2013. Charbonneau asked for the extension two weeks ago, partly because the commission has been beset by staffing issues and is running way behind schedule in hearing witnesses.

The provincial government now wants to see an interim report by the end of January 2014. If the final report is tabled in April 2015, the commission's work will have lasted 42 months -- which could keep corruption scandals alive beyond the current minority government.

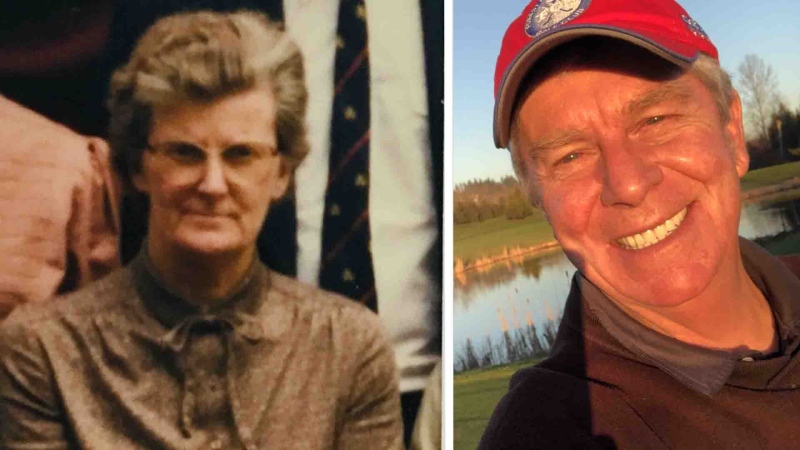

Justice Minister Bertrand St-Arnaud announced the new deadline at a news conference Tuesday in Quebec City.

"It always struck us as essential that the Charbonneau Commission....be able to get to the bottom of things," St-Arnaud said.

"Eighteen months is very long, but the commission says it is necessary to shed (the appropriate) light."

The probe is examining illegal political contributions, corruption in public contracts, and ties that link the construction industry to political parties and the Mafia.

The consequences of the extension are difficult to predict -- on all levels of government. In the last couple of days alone, reports related to the probe have touched on various spheres.

According to one, Montreal might soon be running low on asphalt to fix potholes because its main supplier is now banned from doing business with the city.

Witnesses have described illicit large-scale donations to provincial political parties -- including not just the scandal-tainted Liberals, but also the Parti Quebecois.

At the federal level, the name of a Conservative senator, Leo Housakos, was suddenly raised during questioning Tuesday by inquiry lawyers asking an engineering company boss about the circumstances under which Housakos left the company.

It's unclear why Housakos' name has been raised at the probe, twice now since last December. No allegations of wrongdoing have been made against him. Also, the inquiry is not examining federal politics. But Housakos did once raise money for the now-defunct provincial ADQ.

Later in the day Tuesday, one more engineering firm confessed to taking part in shady political financing schemes.

Dessau Inc. admitted to using a system of false invoices to secure $2 million in cash for difficult-to-trace political contributions.

Corporate donations are illegal in Quebec, as are donations beyond a certain amount.

Dessau, the third-biggest engineering firm in Quebec, said it used contacts at a pair of companies to pass along cash in exchange for a cheque and a 10-per-cent commission.

Vice-president Rosaire Sauriol made the admission while testifying at the inquiry.

The probe has already heard that the country's biggest engineering company, SNC-Lavalin, reimbursed employees who donated to political parties.

Sauriol said his own company president, his brother Jean-Pierre Sauriol, was aware of the scheme. However, he said Dessau stopped the practice in 2009 and, after revealing the details to authorities, paid a fine to cover back taxes and interest.

Sauriol described the political donations as a "cancer," with companies under intense pressure to finance political parties.

The inquiry has heard that representatives from various provincial parties exerted such pressure. That includes the Parti Quebecois, which so far has been less damaged by the inquiry.

Premier Pauline Marois was asked Tuesday about testimony that her party also received hundreds of thousands from engineering firms, and also exerted pressure on companies to donate.

"Our party was not aware," Marois said of such practices.

"Our party did not want that. Our party asked those contributing to the Parti Quebecois to sign personal cheques, for their personal contributions."