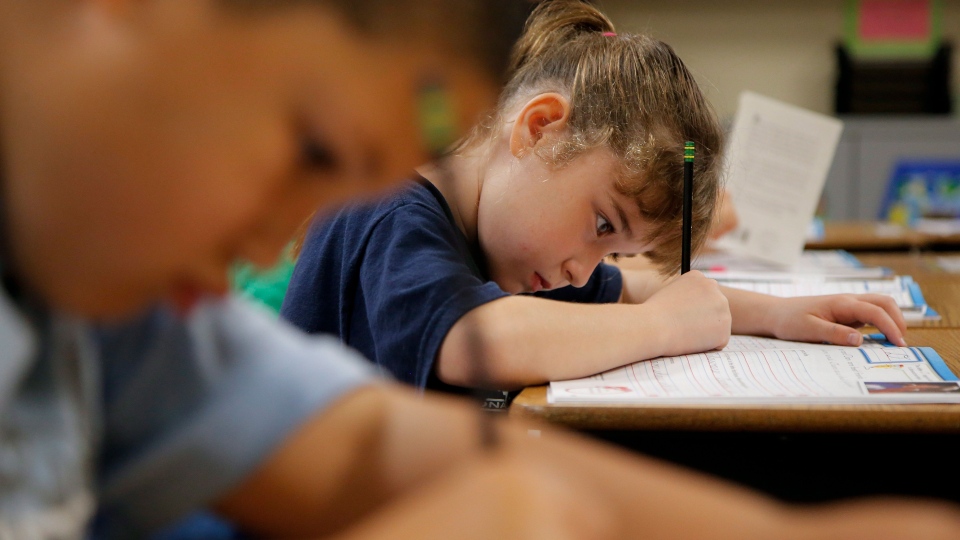

Most parents can remember spending hours practising their handwriting, looping their ‘l’s and ‘g’s and distinguishing their ‘n’s from their ‘r’s. But it seems that learning handwriting in school is going the way of the overhead projector.

More and more teachers are choosing not to teach cursive handwriting, focusing instead on keyboarding and other computer-based communication

In today’s Internet-driven world, do kids still need to be taught cursive in school? Is there any point in learning a skill that fewer and fewer of us are using? Or is it still important for kids to learn to write?

George Couros, the principal of innovative teaching for Parkland School Division in Edmonton, thinks the days of formally teaching handwriting are coming to an end.

He says if video and computer skills are what children now engage in, then that’s what educators need to focus on.

“Technology and literacy are continuously developing … and I think we need to really focus on what we do in school to help kids connect with the world,” he told CTV’s Canada AM this week.

Many parents might lament their children’s lack of ability to craft a handwritten thank-you card, or to make out the handwriting on an old family recipe, but Couros says communication is simply evolving, not disappearing.

“Sending a handwritten note is a nice thing and a nice element to have in our world. But kids are communicating in other ways: using email and texts, and there are other ways of people being nice to each other,” he says.

What schools need to do it to teach children how to communicate in ways that are engaging to them, he suggests.

And like it or not, for most kids, that doesn’t mean the handwritten word. “I’m not saying cursive is totally outdated, but I’m saying that literacy really needs to expand.”

The problem, Couros explains, is that there are only so many hours in a school day, which is why teaching cursive handwriting is not a compulsory topic in most schools -- though it hasn’t been struck off teaching plans either.

“In Alberta education, there is a component of it … But we’re really not spending as much time on it as perhaps we did when we were kids,” he says.

But Jim Brand, principal of Toronto’s Maria Montessori school, says it would be a shame to do away with teaching cursive altogether.

He says in the Montessori program, writing is taught very early, even before reading, because it’s thought that it’s a skill that kids can pick up earlier and that helps to speed up the reading process.

“We believe there is a sensitive period for the acquisition of language, including the process of writing, which is between the ages of zero and six,” Brand said. “So if we address it at that stage, it’s just a natural part of what’s relevant to the child and interesting to the child and what’s natural for them to learn.”

Brand says while he has no problem with teaching kids about current technology, cursive should still be taught as well. He says it’s a skill that helps develop hand-eye coordination, fine motor skills and even creativity.

And, he says, there is something about the typed word that doesn’t inspire creativity the way handwritten work does; he’s even noticed that the quality of work on paper seems better than typed work.

What’s more, the mere act of learning to repeat the letters of cursive aids a child’s development, Brand insists.

“The point is not whether the child learns to write neatly in a cursive hand that’s impressive in a job application. The real interest for Montessori educators is the actual process of learning the cursive,” he says.