WINNIPEG -- Manitoba's highest court has ruled that the family of a man who died during a 34-hour hospital emergency room wait can sue the health authority for a breach of charter and privacy rights.

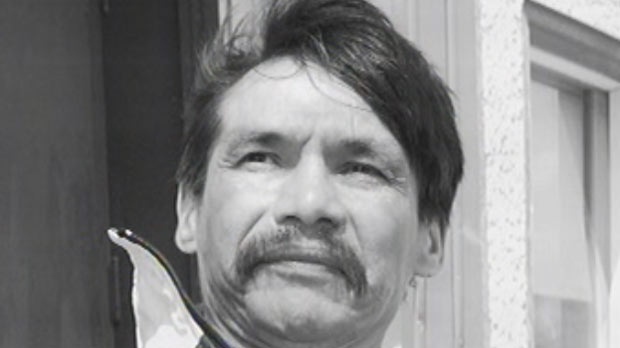

Lower courts struck out the heart of the lawsuit filed by the family of Brian Sinclair, ruling his loved ones couldn't sue because those rights died with him in 2008. Lawyers for Sinclair's family argued it was absurd that the family of a man who died because he didn't receive proper care couldn't sue because he was dead.

After eight months of deliberations, the Manitoba Court of Appeal said that the lawsuit should be allowed to proceed.

Vilko Zbogar, one of the family's lawyers, said the ruling has important implications for the evolution of charter law, as well as the family's pursuit of justice.

"This is absolutely a landmark ruling on charter interpretation and on privacy rights," he said.

"It's important to the family to have vindication for Brian Sinclair's death and it's very important to them to hold the institutions who were responsible accountable for their conduct. They made racist assumptions about why Brian Sinclair was there sitting in his wheelchair throwing up during a 34-hour period and that's what led to his death."

The appeal court also restored the family's right to sue the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority for disclosing private health information about Sinclair after his death.

Robert Sinclair, Brian Sinclair's cousin, said the family won't stop trying to hold health authorities to account "for their shameful conduct both before and after his death."

"We are grateful that the courts will now allow us to do that," he said in a statement.

The 45-year-old double amputee died of a treatable bladder infection caused by a blocked catheter while waiting for care at Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre.

Although Sinclair spoke to a triage aide when he first arrived at the emergency room, he was never formally entered into the hospital's system. He languished in the waiting room for hours, growing sicker and vomiting several times, but was never asked if he was waiting for care.

Rigor mortis had set in by the time Sinclair was discovered dead. An inquest into his death heard many employees assumed he was drunk or seeking shelter, or had been seen and was waiting for a ride.

Despite case law which argues charter rights do not survive death, the appeal court judges found the issue should be argued in court.

"I see no imaginable reason to borrow such a discredited and outdated principle of the common law to the modern age where key values underlying the charter include the affirmation of individual human dignity and respect for the value of human life," Justice Chris Mainella wrote.

Allowing the lawsuit to proceed will "clarify the serious issue of whether redress for a charter violation ends on death when the alleged breach contributed to the death."

Felicia Wiltshire, spokeswoman for the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, said the court decision is being reviewed and the authority is assessing options.

Kelly Dixon, lawyer for the health authority, told the appeal court in September that if the lawsuit had been allowed to proceed, it would have argued that Sinclair's charter rights were not violated. She told the judges the allegations were more a claim of medical negligence than a charter violation.

The health authority has publicly apologized and paid out $110,000 in damages to the Sinclair family.