The incident this week of a mother in Mississauga, Ont. demanding that her son be examined by a “white doctor” is not an isolated incident, say several physicians, who want to see the policies about how to treat such patients made clearer.

The incident on Sunday was caught on video, and showed an unidentified woman repeatedly asking clinic staff to see a “white doctor” who “doesn’t have brown teeth” and “speaks English” to treat her son, who she claimed had chest pains.

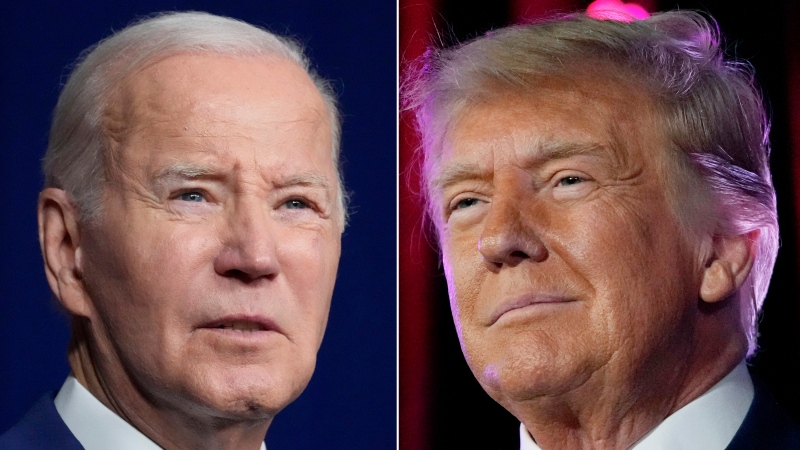

The video sparked international headlines and prompted condemnation from both the Ontario premier and the health minister.

Many doctors say such incidents of racism are not uncommon, but they say navigating the incidents is difficult because there aren’t clear policies on how to handle them.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, which regulates and disciplines doctors in the province, says it does not have a policy to address situations of racism but noted that “the Ontario Human Rights Code states all those who provide services in the province are entitled to do so free from discrimination.”

Ontario Health Minister Eric Hoskins denounced the woman’s words and said the province’s medical community won’t tolerate racism, adding “That kind of hateful and racist behaviour is unacceptable no matter where it happens.”

Premier Kathleen Wynne also stepped into the debate, saying “there is no place for that kind of behaviour, that kind of racism and hatred, quite frankly, in our society.”

But Ontario Medical Association president-elect Dr. Nadia Alam, who practises family medicine in Georgetown, Ont., told CTV’s Your Morning that she has heard a lot of discussion about the incident and thinks there does need to be a policy about how to handle such incidents.

“There is a big concern out there about how to create an environment of safety – not just for ourselves, but for the... medical residents, for our staff, for the other patients,” she said.

Then there is the question of the patient themselves, she said.

“How do you treat them when they no longer trust you and all they see is your skin colour?”

Alam says the CPSO is clear that physicians who feel physically unsafe with a difficult or abusive patient are allowed to remove themselves from the situation.

“However, what do you do when it’s something like this, when it’s someone hurling out vicious slurs? You feel unsafe but your life is not in danger. It’s a grey zone. That kind of grey zone has to be explored so that we can all navigate it more easily,” Alam said.

Alam said she herself has faced racism as a child, as a medical student, and as a practitioner and says it’s insulting to be devalued simply because of her race.

Dr. Kulvinder Gill, the president of Concerned Ontario Doctors, has also dealt with racism in her work and says this isn’t a new issue.

“This has been happening for decades, but never as overt as this,” she said.

Dr. Gill noted that it used to be that the system could turn a blind eye to the problem, but amateur videos and social media are changing that, forcing the issue into the open.

“I think there’s an opportunity to start having a dialogue in the medical community about this,” she said.

Alam said doctors worry not just about their personal safety in incidents like the one in Mississauga, they also worry about their professional safety.

If doctors refuse to treat a patient, for example, they may worry about a complaint being filed against them with the CPSO.

And even if they do treat them, medicine is never perfect, and not all patients get better after seeking care. So some physicians worry patients might also file a complaint if they believed their doctor was incompetent because of their race.

“If this person doesn’t already trust my knowledge and training, are they more likely to make a complaint?” she wondered.

“Those are questions that we need to explore and answer.”