Officials in Hong Kong will soon be able to block people from entering or leaving the territory, raising concerns over the possibility of mainland Chinese-style "exit bans" being used to prevent activists and former lawmakers from leaving.

Authorities in mainland China routinely impose similar travel bans on dissidents and foreign citizens, including those facing civil cases, essentially trapping them in the country while a case winds its way through the Chinese court system.

The United States government has previously denounced such bans as "coercive," saying they are used "to compel U.S. citizens to participate in Chinese government investigations, to lure individuals back to China from abroad, and to aid Chinese authorities in resolving civil disputes in favor of Chinese parties."

In response to a CNN story earlier this year about potential risks for foreigners traveling to China, the country's foreign ministry said this was "completely inconsistent with the facts."

"China has always protected the safety and legitimate rights and interests of foreigners in China in accordance with the law," the ministry said.

Under the new Hong Kong regulations, which come into force on August 1, the city's immigration director will gain new powers to stop people entering or leaving the city, without a court order, including banning airlines from carrying certain passengers.

Despite widespread opposition to the law from legal and human rights groups, the bill passed easily due to the current makeup of the legislature. There are currently only two sitting opposition lawmakers, after the majority of pro-democracy members resigned in protest last year at the expulsion of several of their colleagues.

In a submission regarding the legislation, the Hong Kong Bar Association had criticized the "extraordinary" and "apparently unfettered power" given the immigration director -- an unelected official -- under the new regulations, warning that the changes could breach Hong Kong's de facto constitution, Basic Law, as well as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which the city is a signatory.

Speaking Wednesday, John Lee, Hong Kong's security secretary, dismissed such concerns, criticizing the "deliberate distortion" of the legislation and the "emotionally inflammatory language" around it. Lee denied that the new law could affect the freedom of movement of Hong Kong residents.

Lee said that the new powers introduced under the law would be applied only to inbound flights -- preventing people from entering rather than leaving the city -- and be used to target illegal immigrants.

However, activists and lawyers contest that the legislation does not adequately differentiate between inbound and outbound travelers, and argue that it could be used against people trying to leave Hong Kong.

Speaking to public broadcaster RTHK, barrister Chow Hang-tung said that irrespective of the law's intended use and target, its passage marked a worrying scaling back of residents' rights.

"If you can stop a Hong Kong citizen from boarding an inbound flight, meaning that anyone who's left Hong Kong cannot come back, that's also a very worrying situation, right?" said Chow. "So, just by limiting this to inbound flights doesn't really allay our concern," she added.

LOOKING FOR AN EXIT

Since the passage of a national security law last year which banned secession, subversion and collusion with foreign powers, there has been a concerted crackdown on the Hong Kong opposition, with almost every prominent activist and former lawmaker currently facing prosecution.

Multiple prominent figures have fled overseas in the past year rather than face prison time, including Ted Hui, who slipped out of the city in November while on bail, on the pretense of attending a climate change conference in Denmark. Hui has since gone into exile in Australia.

Prosecutors were already able to request that courts confiscate the travel documents of defendants believed to be a flight risk, but activists and lawyers argue the new law could potentially make it far easier to bar anyone from leaving Hong Kong, and could also enable the immigration director to issue exit bans against people not facing any charges.

While Hong Kong has additional constitutional protections not available in mainland China, the potential for such exit bans, particularly against foreign citizens, could raise alarm within the business community, which has so far weathered the decline in the city's freedoms without too much protest.

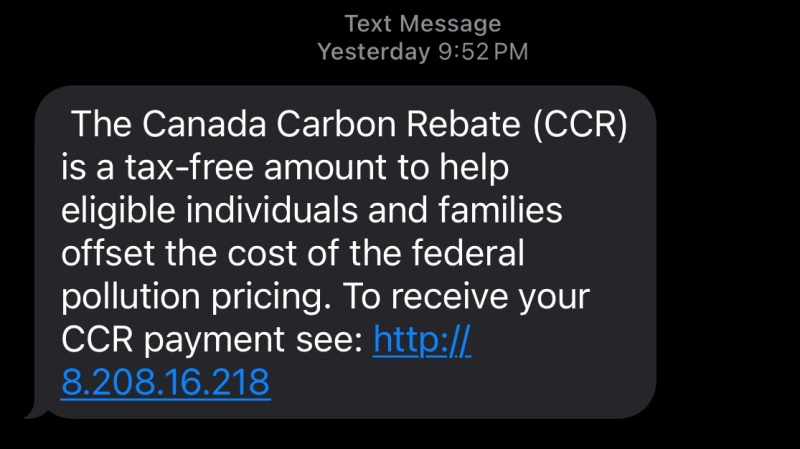

This month, U.S. lawmakers reintroduced a bill designed to counter Beijing's coercive use of exit bans, which would deny a visa to the U.S. to any Chinese official found to be involved in blocking Americans from leaving China. In a statement, the lawmakers said that at least two dozen U.S. citizens had been trapped in China in this fashion over the past three years.

"The Chinese government's use of 'exit bans' is a gross violation of international human rights norms," Senator Edward Markey said in a statement, highlighting the case of siblings Cynthia and Victor Liu, and their mother, Sandra Han, who have all been trapped in China since they traveled there in June 2018 to visit an ailing relative.

"Cynthia and Victor are two promising young people have had their lives put on hold while being forced to remain in a country where they face regular surveillance, harassment, and threats from Chinese authorities," Markey said. "This legislation will hold accountable those Chinese authorities who participate in this sinister practice."