TORONTO -- As Americans choose their next president, questions have swirled around the voting itself, with long lines for in-person ballots and confusion over how long after Election Day different regions will accept mail-in ballots.

Election fraud -- or unfounded claims of fraud -- can cause huge damage to whomever takes office after an election. U.S. President Donald Trump hasn’t given a clear answer as to whether he’ll accept the results of the election if he loses, instead seeding doubt about the legitimacy of the election whenever asked the question.

In a country defined by its democracy, the legitimacy of the government depends on the legitimacy of the election, and history has shown that a contested election can lead to dire consequences for the most disenfranchised within the country.

And it's happened before in the U.S.

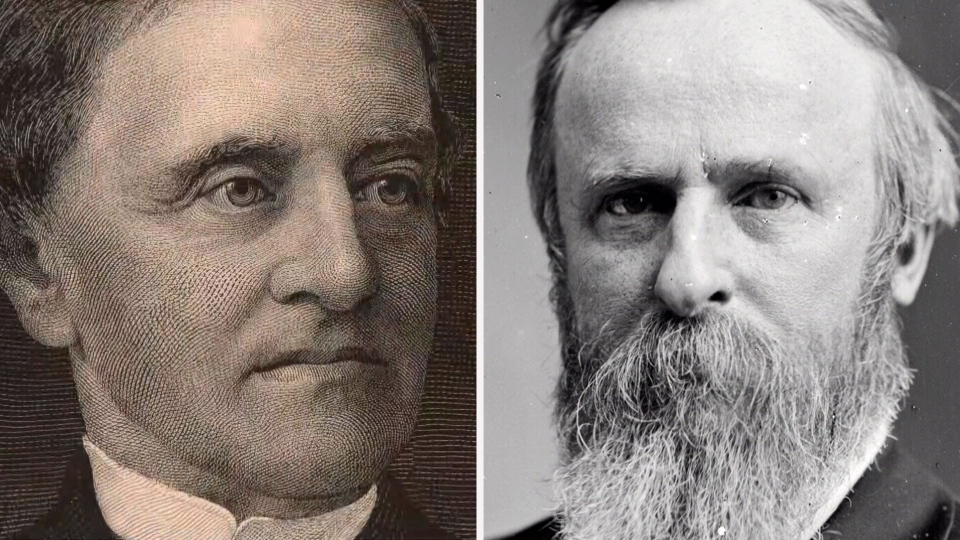

More than a decade after the Civil War ended, Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes and running mate William Wheeler were still campaigning to preserve the victory.

This was the election of 1876, when those who could cast votes included newly freed Black men.

The Emancipation Proclamation, brought in by Republican President Abraham Lincoln, had officially freed Black men and women from the bonds of slavery in 1863, although many former slaves did not know they were free until more than two years later, as enforcement of the proclamation relied on Union troops advancing into the south.

During the 1876 election, in at least three Southern states, white racist mobs still forced Black men to vote Democrat, or not at all.

The Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden won the popular vote, but finished just one electoral vote short of victory, with 20 electoral votes in dispute due to allegations of cheating.

A special 15-member commission with a Republican majority tried to make Hayes president, but House Democrats objected.

Then, in a secret meeting at a hotel, an already chaotic election was decided in a backroom deal.

Democrats agreed to let the Republicans have the presidency, on one condition.

In the post-war era of Reconstruction, federal forces had remained in the former Confederate states to make sure they were giving the rights of citizenship to freed slaves, which Southern whites detested.

Not long after Hayes was inaugurated, he paid the price Democrats had demanded, and pulled the remaining federal forces out of the South.

Reconstruction was over. The party that had freed Black Americans from slavery had betrayed them.

Unsupervised and back in control of Southern states, the former slave masters brought in unconstitutional Jim Crow laws, disenfranchising Black Americans and subjecting them to generations of brutally enforced segregation.

Among the injustices visited upon Black Americans during this time included attempts to block them from voting, whether by intimidation or by instituting voter restrictions aimed at singling out Black Americans, such as an annual poll tax and a literacy test that allowed a county clerk -- always white, according to the Constitutional Rights Foundation -- to decide who fit their definition of literate.

It was not until the Civil Rights movement of the following century that the work of reconstruction resumed.

William E. Chandler, later a U.S. senator, summed up the sell-out by Hayes in a letter to the Republicans of New Hampshire in 1877, saying that “to abandon the principles of his own party would […] proclaim his doubts as to the rightfulness of his own election.”

The lesson of history: if an election loses its legitimacy, then so does the presidency, and the ones whose lives are affected the most are rarely the people sitting in the White House.