VANCOUVER – It’s 8:30 p.m. on a chilly, West Coast evening and Jessica is dancing in an alley.

In a squeaky, childish voice she twirls and twirls. Nonsense pours from her mouth. Her thin jacket is a blur of red against a grey concrete wall covered by graffiti.

She’s on cloud nine – far away from this place – 20 minutes after she and her friend Patricia took a hit of what they think is heroin. But there’s no way to be sure.

“Everything except heroin,” says Jessica in a relaxed, sing-song voice. “I honestly can not tell you the last date since I’ve done real heroin.”

With stronger, cheaper synthetic opioids such as fentanyl being cut into street drugs, there’s no way to know how much is too much, that could lead to an overdose that could stop her breathing.

And suddenly, Jessica drops, motionless, to the pavement.

“Jess? Jessica! Jess,” shouts Patricia, who runs down the alley to where she’s lying. “Are you all right?”

There is a moment when it seems like she won’t wake up. But then Jessica’s legs curl up, crab like, contorted over her head.

She begins to growl and purr, rocking from side to side, oblivious to the cantaloupe-sized rat that’s just run by her.

It could have been a lot worse. Jessica is one of at least 6,000 drug users who call Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside home. And she lives in a province where in December five people a day died of drug overdoses.

Here, in the alleys, among the overflowing dumpsters, the smells of decay and dark figures slumped in piles of rags, is Canada’s ground zero in addiction. In B.C., 922 people died of an overdose in 2016.

But it’s an epidemic that has already spread across Canada with upwards of 1400 deaths last year. That includes addicts, but also teenagers looking to have a good time.

They die because they think they have taken cocaine, or the party drug ecstasy, or a prescription painkiller, but it turns out to be something else. Usually the synthetic opioid fentanyl, a synthetic pain killer whose name has become synonymous with death.

As of this year, fentanyl has been joined in the streets by it’s even more potent cousins: carfentanil and W-18.

Together they form a lethal trifecta that’s ravaged emergency care resources and is forcing policy makers to rethink what addiction is.

“I talked to one user, about a month ago, who came in on an overdose and I started to tell him about the risks,” recalls Dr. Dan Kalla, the head of the emergency room at St. Paul’s Hospital, which handles most of the overdose cases in the region.

“He said, ‘you don’t need to tell me, I woke up beside my girlfriend who was dead’ the week before. He’s aware that this drug killed her; he’s still using that drug and almost dies of it himself. To me that speaks of the incredible hold this thing has and the senselessness of it.”

Kalla compared the opioid crisis to AIDS. At its peak in 1994 in B.C., AIDS killed 267 people – while more than three times as many people died from overdoses last year in BC.

Kalla, like many others on the frontlines of addiction, says it’s time for Canada to advance past the 1971 “war on drugs” mentality, that addiction is more complex than being reckless or a degenerate and requires a new and radical approach.

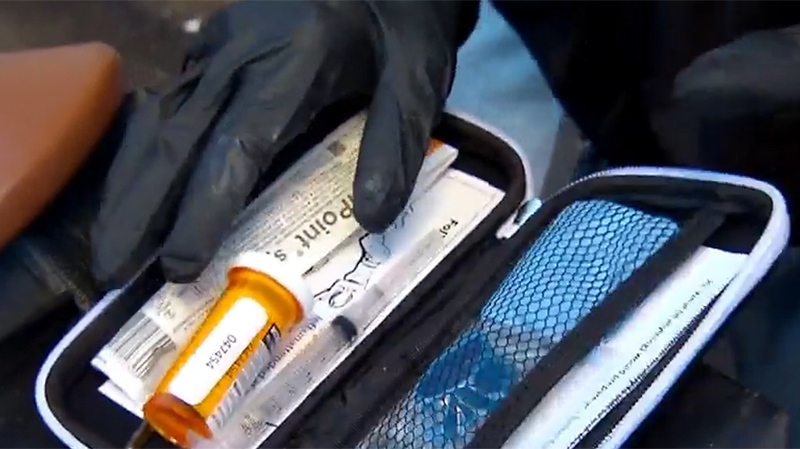

A W5 investigation of those new approaches shows health care workers scrambling to catch up to the astonishing death toll. There are new, specialized paramedics that just handle overdoses. Officials have deployed an army-style mobile medical hospital. And another clinic has opened that offers prescription heroin, paid for by the government.

Vancouver’s main supervised injection site, Insite, has been operating since 2003. It’s now been joined with unofficial volunteers looking to watch users inject and save their lives if something goes wrong.

It all may be making a difference: the number of deaths has dropped to three a day in February. It’s still a lot. But the turnaround could point the way for the rest of the country, which don’t yet have these supports.

Health Canada has approved three supervised injection sites in Montreal, but they have yet to open yet. And Toronto’s three sites are expected to open this summer.

Those on the ground who have to see these deaths up close have a message for the rest of the country.

“Prepare for it, it’s coming,” says Dr. Kalla. “This toxic, lethal drug is out there and it will take hold in other communities, I guarantee it. Be prepared.”