TORONTO -- Archeologists in the U.K. may have unearthed new evidence on where the iconic stone circle of Stonehenge originated from.

Working in the Preseli Hills of western Wales, archeologists found the remains of what is now considered Britain’s third-largest stone circle that they believe was dismantled and moved 280 kilometres to Salisbury Plain and rebuilt as Stonehenge.

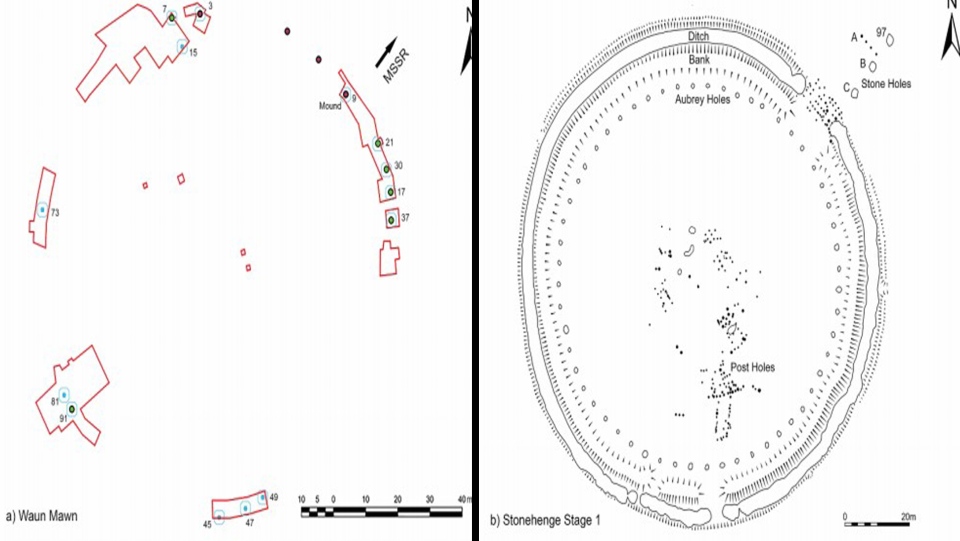

The study, published in the February edition of the Antiquity Journal, names the uncovered stone circle as “Waun Mawn,” and found that it has an identical diameter to the ditch surrounding Stonehenge, and a structure aligned on the midsummer solstice sunrise, also like Stonehenge.

A plan of the currently excavated sections of Waun Mawn and Stonehenge 1, showing the similarities in both structures (Antiquity Journal/credit: K. Welham & I. de Luis)

The stone quarries that supplied Stonehenge with its “bluestones,” which is the name of the smaller stones at the site, is located close by the Waun Mawn – pointing to a shared source of stone for both sites.

Stonehedges’ bluestones are thought to have been erected 5,000 years ago, centuries before the larger stones known as “sarsen stones” were brought to the site.

The research project, led by British later prehistory professor Parker Pearson of University College London, had previously excavated two bluestone quarries – and it was through this work that the Waun Mawn - Stonehenge connection was hypothesized.

“In 2008 our excavation of an Aubrey Hole (one of 56 pits in a circle at Stonehenge, dating to the beginning of the monument) confirmed my hunch that these Aubrey Holes had held bluestones right at the start in 3000-2900 BC,” Pearson said in an email to CTVNews.ca.

“I realized that to discover the origins of Stonehenge we had to shift our project from Stonehenge to where the bluestones came from.”

When digging at the new Waun Mawn site, scientific dating of charcoal and sediments in the stone holes confirmed that the Waun Mawn stone circle was erected around 3400 BC, years prior to the first stage of Stonehenge built in 3000 BC.

“It looked as if for many of the stones [excavated around Waun Mawn] there was a big gap in time between quarrying and erection at Stonehenge,” Pearson explained. “One of the stone holes at Waun Mawn had stone chippings and a cross section that can be matched with one of the bluestones standing at Stonehenge.”

As to how the archeologists found Waun Mawn in the first place, Parker claimed the location was “in a 100-year-old book.”

Archeologists had surveyed the site during the First World War and “catalogued it as a stone circle based on the arc of four surviving stones,” Parker explained, but said that later generations of archeologists had either ignored Waun Mawn or “doubted it had ever been a circle.”

“In 2011 we did geophysical surveys [at Waun Mawn’s location] but these turned up nothing. Not realizing that this was due to the unresponsive soil conditions, we figured it was just an arc of stones and not a former circle,” Parker said.

After six years of “fruitless searching,” a colleague suggested they try the location again. “It turned out he was right,” Parker said, and the team unearthed the stone circle.

The Waun Mawn discovery is a new chapter in the lore and history surrounding Stonehenge, which has gone through many iterations over the centuries.

Wiliam Stukeley, the English antiquary and a forefather of archeology who pioneered the investigation of Stonehenge, “thought Stonehenge was a druid's temple because it reminded him of the facades of Greco-Roman temples… he realised it was prehistoric but only had Julius Caesar's book about ancient Britain as a guide, and he mistakenly attributed it to Iron Age druids,” Parker explained.

Stonehenge has frequently featured in myths surrounding Merlin and other druidic characters.

Parker said subsequent study of the rubble left inside Stonehenge “shows it was never a temple,” but best understood as a type of “memorial-style monument.”

And it was a chance comment that gave Parker his research initiative as to why Stonehenge was built.

In 1998 the renowned archeologist Ramilisonina, who hails from Madagascar and was a colleague of Parker’s, came to see Stonehenge and was “amazed that no one had figured out the obvious,” he said.

“In Madagascar people build in stone for their ancestors (tombs and standing stones) but build in wood for the living,” Parker explained in his email.

Ramilisonina’s “simple observation” ended up being the “driving hypothesis” in Parker’s research at Stonehenge.

“I had to find out if he was right – and 17 years later it seems he was,” Parker said, “We found lots of burials inside Stonehenge and found lots of formerly wooden houses…just three kilometres from Stonehenge.”

Parker said most of the people buried at Stonehenge were women, a discovery that seems to be “the case for most of the many other circular burial enclosures across Britain.”

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Parker hopes to return to the dig at Waun Mawn later on this year.