Historians in the U.K. perusing eBay stumbled upon a rare machine believed to have been used by Adolf Hitler to exchange top secret messages during the Second World War.

A Lorenz teleprinter, which resembles a typewriter, was recently advertised on eBay for the equivalent of $18.

National Museum of Computing volunteer John Whetter said his colleague was searching for spare parts for British teleprinters when he came across an item described as a German telegram machine.

"We could see it was Lorenz teleprinter, so we jumped in the car and went down to Essex," Whetter told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview from Milton Keynes, U.K.

Whetter said the teleprinter was being stored in a garden shed, and its previous owner said it once belonged to a neighbour who had passed away.

"We started to clean it up, and as we did so we noticed a special plate which was engraved with a German swastika and an eagle, and also a code number which meant it was a German military machine," Whetter said.

He said the printer is part of the highly sophisticated Lorenz system that Hitler had used to communicate with his top commanders during the Second World War.

The museum was then tasked with locating a Lorenz SZ42 encryption machine that works in conjunction with the teleprinter, which it was able to track down at the Norwegian Armed Forces Museum in Oslo.

Only four such devices are known to exist today.

The Lorenz SZ42 wheels. (Photo courtesy Charles Coultas / The National Computing Museum)

Whetter said, after about 15 months of negations, the Norwegian government agreed to loan the encryption machine to the National Museum of Computing.

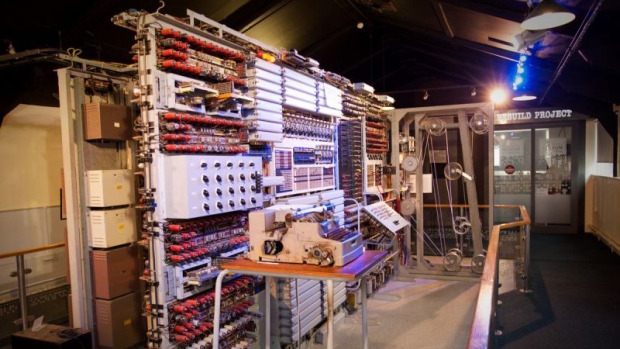

The museum at Bletchley Park, the now-famous home of British codebreaking during the Second World War, had spent the better part of the last 20 years rebuilding the British equipment used to crack the Lorenz code.

"Once we'd done all that, we had no German equipment," Whetter said. "We wanted to pursue the other side of the equation. How did the German transmit and receive these highly secret messages, which the brilliant people at Bletchley Park managed to crack during wartime."

Coding equipment on display at Bletchley Park. (The National Computing Museum)

The museum now has all the coding equipment used by both British and German forces during the Second World War under one roof.

But one piece of the puzzle needed to restore the Lorenz machine to working order remains missing – the machine's motor.

While many of the machine's missing electrical components can be sourced relatively easily, the museum says the missing motor is proving much more difficult.

An estimated 200 Lorenz coding machines were manufactured, and most were destroyed by German forces after the war.

The museum is appealing to the public to help find a replacement, or manufacture a new one.

When asked about the chances of finding an original motor, Whetter teased: "You have a better chance of being struck by lightning…but it may in another garden shed somewhere."

But he noted that the museum has already heard from companies in the U.K. that have expressed an interest in manufacturing a replacement motor.

The National Museum of Computing said it does not know what the present-day value of the Lorenz system is pegged at, and it’s not very interested in its monetary value.

"The museum would never sell it," communications official Stephen Fleming said. "Its value is historic, and it's an inspiration to youngsters.”

Ontario prof credited with cracking code

Historians credit the Allies’ ability to break the top-secret message of German High Command to shortening the war and saving countless lives.

Bill Tutte worked as a mathematician at Bletchley Park and he is credited with deciphering the German military encryption codes.

Sue and Ken Flowers with Bill Tutte (nephew of Bill Tutte) and Patricia Tutte. (Photo courtesy Charles Coultas / The National Computing Museum)

"Tutte was able to work out the logical structure of the (Lorenz) machine without ever having seen it," Fleming said, noting that his work was only recognized years after the war ended.

"To be able to decrypt the German messages from the absolute highest intelligence level shortened the war by considerable time and saved hundreds of thousands of lives," Fleming said.

Tutte joined the faculty at the University of Toronto in 1948 and accepted a position at the University of Waterloo in 1962 later joined the University of Waterloo.

In 2001 he was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada.

He died in 2002 in Kitchener, Ont.

Whette said the code-breaking work that had taken place at Bletchley Park was kept secret for several years after the Second World War had ended.

"Quite a few people involved never, ever got the recognition they deserved for this because it was kept secret," he noted.