Scientists at a Canadian university have found a link between Mars’ rocky surface and methane in the planet’s atmosphere, akin to the ground “breathing in and out.”

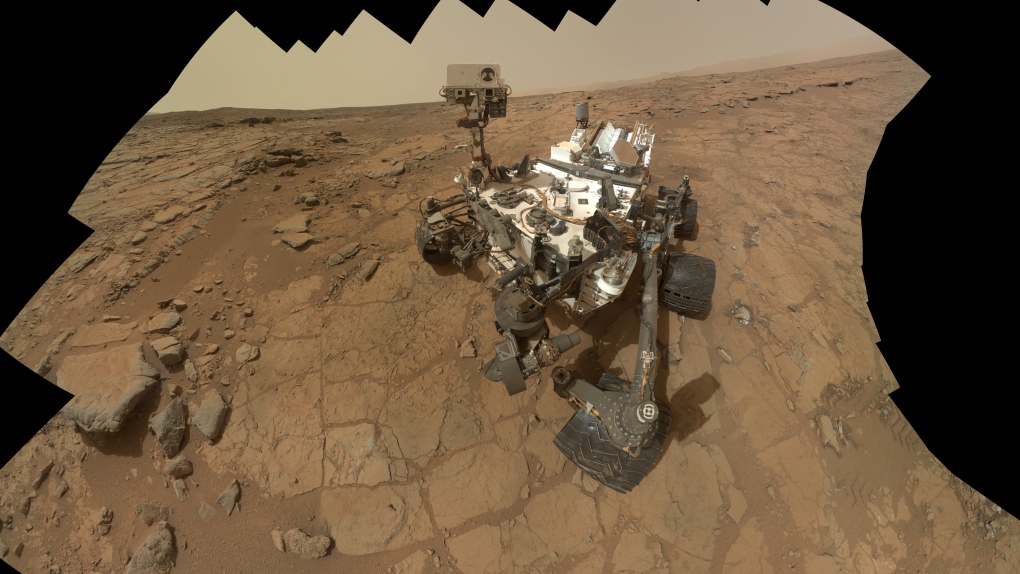

Researchers believe a process in the planet’s subsurface controls how much methane is released into the atmosphere above Gale Crater, the location where NASA’s Curiosity rover landed.

The new study, led by John Moores, an associate professor at York University’s department of earth and space science and engineering, claims to have found evidence of the connection.

“This study shows that the methane seen by the Curiosity rover likely originates in the subsurface of Mars,” Moores said in a statement.

“We are also able to explain a likely mechanism for producing the seasonal cycle in methane levels that the Curiosity rover has recorded.”

In the new study, researchers developed a computer model of the movement of methane through the subsurface and compared how much methane found its way into the atmosphere to the amount measured by Curiosity.

Previous research has shown that the amount of methane varies from season to season at Gale Crater. There is more methane in the atmosphere when it is warmer and less when it is cooler.

“We were a little stumped at first as to why you would have that variation,” Moores told CTV News Channel Sunday.

“But it turns out that it looks like it’s the ground breathing in and out, so it’s actually an interaction with the soil that’s going on there.”

Measurements from NASA’s Curiosity rover has hinted at reservoirs of the gas below the planet’s surface, a York University press release stated.

“When it’s cold the methane sticks to that soil so most of it gets exhaled from the subsurface, and when it’s warm more gets emitted, it’s able to move through and into the atmosphere,” Moores added.

“So it’s actually interaction between the ground and any reservoirs underneath the surface with the atmosphere itself.”

Moores says until now, there has been no convincing explanation for how the seasonal cycle in methane came about.

“We expect these processes to operate on Mars because they certainly happen on the Earth, so it’s not surprising,” Moores said.

“We were surprised however, by how well everything matched up once we started to change how the soil and the methane interacted with one another.”

This new research provides a plausible mechanism for producing this effect and calculates how much methane needs to be involved, the university said.

“On the Earth most of the methane we have in the atmosphere comes from life,” Moores told CTV News Channel.

“But on Mars it could be something else, we’ve geological processes and other things going on there as well.”

Moores said that with the work his team has done, he can’t exclude the possibility of life on Mars.

“We’re kind of agnostic in the work that we did as to whether or not that’s where the methane is coming from,” he said.