TORONTO -- We’ve all seen an action movie sequence involving the hero peeling off a hyper-realistic mask in a dramatic moment of revelation, but could a real-life mask fool people as well as the cinematic ones do?

A new study presented participants with images comparing a real human face and a person wearing a silicone mask, asking them to identify the fake -- and found that one fifth of the time, participants got it wrong.

Researchers call it a ‘Turing Test’ for hyper-realistic masks, referring to Alan Turing’s test for the success of artificial intelligence, based on a human being able to judge whether they’re speaking to a robot or another human.

And, while AI might not quite be there yet, when it comes to hyper-realistic masks the technology is apparently getting good enough to cause real confusion, presenting uneasy ethical questions as well as potential issues for law enforcement.

Rob Jenkins, one of the co-authors of the study published earlier this month in Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, told CTV’s Your Morning that the experiment is “very simple.

“We just show people pairs of photographs -- one is always a real face, the other is always a mask, and the task is simply to indicate which one is the mask,” Jenkins said. “Now, if people can tell the difference, they should pick the mask every time. But that’s not what we found. In fact, people picked the real face instead of the mask on at least 20 per cent of occasions, so this tells us that people are having a really tough time telling the best of these masks from real faces.”

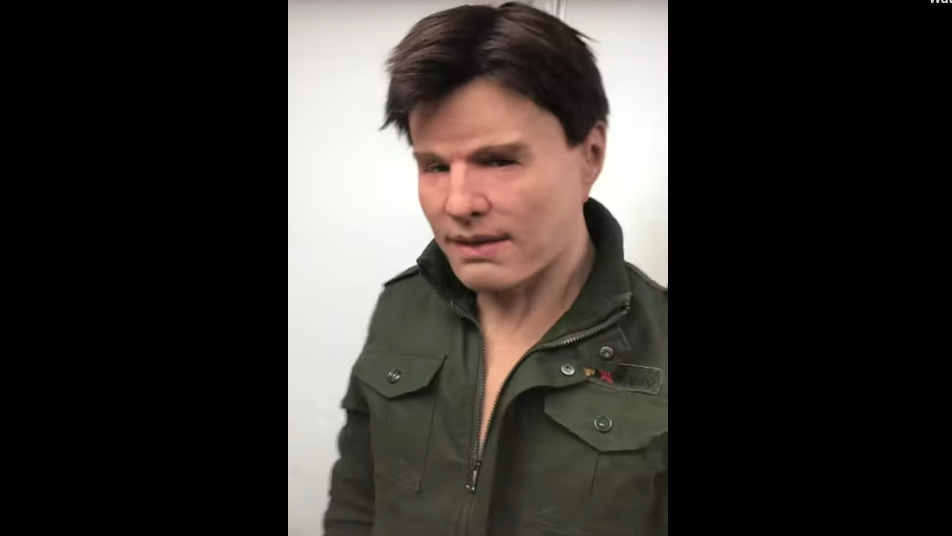

Masks have come a long way from just papier mache and paint. The hyper-realistic masks featured in the study are made out of silicone and are meant to depict a realistic human head, including every freckle and wrinkle. They can even somewhat adhere to the wearer’s movements, so that the mask moves as the person opens and closes their mouth.

The effect can be disorienting.

And in real life, it’s unlikely to be called out.

Earlier research that Jenkins was part of in 2017 tested whether passers-by noticed whether a person was wearing a mask in a live situation. Out of 160 participants, only two people spontaneously reported having noticed a mask. In the 2019 study, it is noted that, in a real-life social situation, people might be “reluctant to inspect or to discuss the appearance of a person who was physically present.”

The idea behind the new study was to remove that social context by just using images.

Participants were shown low-realism masks -- such as colourful masquerade masks -- in some of the images to control for their base level of identification.

In one round of the experiment, participants had only 500 milliseconds to choose which of the images was not a mask, and in a second round, there was no time limit imposed.

Participants got an almost perfect score when it came to identifying the low-realism masks (98-99 per cent) regardless of time limits. But that changed with hyper-realistic masks.

When participants had to think fast, they only found the human face 66 per cent of the time. When given unlimited time to view the images and make a decision, they improved, but only marginally. They still chose the mask over the human face around a fifth of the time.

“The implication is not merely that the hyper-realistic masks looked human,” the study reads. “In some cases, they appeared more human than human.”

Hyper-realistic silicone masks -- such as those made by Realflesh Masks, a Quebec company -- are used frequently in film and television. But a growing concern is that these masks, which can retail for anywhere from $550 to $2,000, are showing up as a means for would-be criminals to disguise themselves.

“If someone robs a bank, say, wearing a balaclava, then police will be fully aware that they don’t know what the robber looks like,” Jenkins pointed out. “But if someone robs a bank wearing a mask that passes for human, then they might think they know what the robber looks like, but be very much mistaken. And that can lead the investigation down the wrong path if they’re looking for someone of the wrong age or the wrong race or the wrong gender.”

In 2014, Ian Marier from Realflesh Masks was able to help capture a serial bank robber after viewing an FBI appeal for information and recognizing a mask he had made himself.

Before Marier got in contact with the FBI, they believed they were looking for a white man in his 50s or 60s. The suspect they arrested with Marier’s information was a 35-year-old Black man.

Jenkins said that he was aware of around 40 cases worldwide where similar situations occurred with the masks.

The study also revealed that racial bias played a part: the likelihood of a participant correctly distinguishing human faces from masks was lower when they were looking at images involving people of a different race than their own.

The data was collected in the U.K. and Japan “to test for other-race effects,” according to the paper, and included an equal number of images of Caucasian and Asian people (or masks) in different sets for participants to scrutinize. Participants took longer to react to images of “other-race comparisons,” as opposed to “own-race comparisons,” and their ability to identify a mask went down by 5 per cent in those cases.

The study theorized that “out-group dehumanisation blunts the distinction between real faces and hyper-realistic face masks,” but added that broader research would need to be done to look into the real implications.

Jenkins said they were “surprised,” by the results.

“Because some people are skeptical, and tend to be overconfident, say, ‘Oh well, I would be able to tell the difference,’” he said.

So could we be only a few years away from that ‘Mission Impossible’ style of disguise? Maybe. The study pointed out that this technology is likely to just keep getting better.

“People are rightly wary of photorealistic images because they know that images can be manipulated,” the study concluded. “We may be entering a time where the same concerns apply to facial appearance in the real world.”