Pre-historic humans were roaming North America and carving up mastodons for food more than a thousand years earlier than previously thought, according a new research paper.

Archaeologists say a stone knife and mastodon remains found at the bottom of a Florida river are "unequivocal evidence" that humans inhabited the Americas 1,500 years earlier than once believed. The discovery is expected to shake up the theoretical timeline around human migration to North America, as the first archaeological proof that humans were present in the southeastern U.S. some 14,550 years ago.

The discovery also shows humans and mastodons co-existed in the same geographical region over the last two millennia before the beast became extinct.

The artifacts were unearthed at an underwater dig site in Florida, and have been radiocarbon dated to 14,550 years ago. The tusk and other mammoth remains were found during a dig in 1993, and the knife was uncovered in a subsequent dig, which took place from 2012-2014. Multiple radiocarbon dating tests of the artifacts and the sediment layers surrounding them have confirmed their age, according to the study published in the journal Science Advances on Friday.

Study co-author Michael Waters of Texas A&M University called the discovery a "major leap forward in shaping a new view of the peopling of the Americas at the end of the last ice age," in a conference call with reporters. He said for years, the scientific community has resisted suggestions that there might have been humans in the Americas before the Clovis people, who were thought to have settled the region first, approximately 13,000 years ago. "Today, that viewpoint is changing," Waters said.

Genetic studies have hinted that humans were in the Americas before the Clovis people, but this new discovery is the first to meet the "gold standard" of proof on that issue, Waters said. "The site provides unequivocal evidence of human occupation that predates Clovis by over 1,500 years," he said.

A close-up photo of a biface as found in 14,550-year-old sediments at the Page-Ladson site in Florida. (Jessi Halligan / Florida State University)

Pre-Clovis evidence

Scientists believe the first humans crossed over to Alaska from Russia some 15,000 years ago, during an ice age when sea levels were lower and a land bridge existed across the Bering Strait. The exact timing of the migration is unclear, but it is thought to have occurred during a period of dramatic environmental changes on Earth. Those changes persisted for thousands of years, eventually triggering mass extinctions among North America's larger-than-human animals, like the camelops (giant camel), the Jefferson's ground sloth (giant sloth), the dire wolf (giant wolf) and the mastodon.

Humans were primarily nomadic hunter-gatherers in that era, and did not leave behind many artifacts, aside from a few stone tools.

Most archaeological evidence from early humans has been attributed to the Clovis people, an early, innovative culture that hunted mammoths using distinctly-shaped stone spears. However, a few archaeological sites have been radiocarbon dated to predate Clovis.

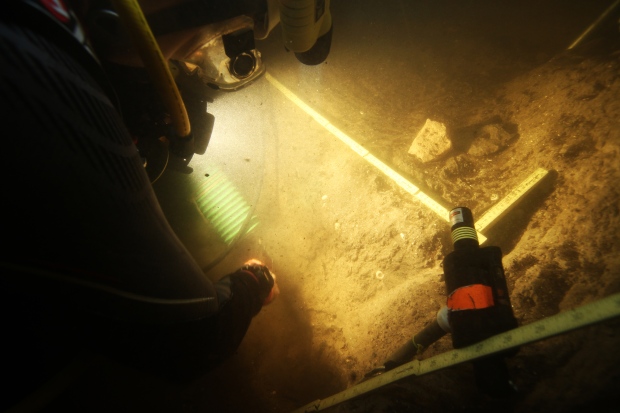

The tusk and stone tools, including stone flakes from the tools' manufacturing, were unearthed at what has been dubbed the Page-Ladson dig site, nine meters below the surface of the Aucilla River. Divers first excavated the site during a prolonged dig in the 1980s and 1990s, when the mammoth tusk was found, along with stone artifacts. However, scientists did not seriously entertain the possibility that humans might have made the cut marks on the tusk, because that would not fit with the Clovis theory, Halligan said.

"The radiocarbon dates they got from this layer showed it to be more than 14,400 years old, which was an impossible age for the scientific community to accept at the time," said study co-author Jessi Halligan, of Florida State University. "It was well accepted that the Americas were colonized by the Clovis people who arrived on the continent over the Bering land bridge no longer than 13,500 years ago at the oldest."

Co-principal investigator Michael R. Waters, right, and CSFA student Morgan Smith examining the biface in the field after its discovery. (A. Burke / CSFA)

Waters says the Page-Ladson discovery likely supports the theory that another archaeological dig site, in Monte Verde, Chile, may also have been left behind by a pre-Clovis culture. It could also open up a renewed search for other ancient sites, as archaeologists come to accept that there were cultures in the Americas before Clovis, he said.

"There is still a terrific amount of resistance to the idea that people were here before Clovis," Waters said. "And I think the beauty of the Page-Ladson site is that it provides everything that people would want to see (as evidence)."

So hungry they could eat a mastodon

The mastodon remains and stone tools were found at the edge of a bedrock sinkhole that was probably a pond at the time the animal died, the researchers said. It's unclear if the beast was killed by a human or if it died by natural causes, but its position near the sinkhole suggests the pre-historic humans knew how to track their prey to a water source, the study said.

A diver works underwater at the Page-Ladson site in Florida. (S. Joy / CSFA)

"We know that they were very smart about where water was found," Halligan said. She suggested the pre-Clovis humans were probably good hunters with intimate knowledge of the landscape and migration patterns of their prey, meaning they would have known the best spot for a mastodon to stop for a drink.

However the mastodon died, University of Michigan archaeologist Dan Fisher said scoring marks on the mastodon's tusk show the animal was butchered for its meat.

"The marks made by the tool can be as diagnostic about the humans who used it as the tools themselves," Fisher said. Mastodon had a great deal of "nutritious tissue" at the base of their tusks, so the early humans who butchered it were likely cutting their way in to access that fleshy part, he said.

A partially reassembled mastodon tusk is shown. (DC Fisher / University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology)

Archaeologists also found evidence at the site that the humans may have had dogs at their sides while pursuing the mastodon.

The Page-Ladson site is the oldest human archaeological site in the southeastern United States, and one of only a handful in all of the Americas that date back to more than 14,000 years ago. However, Halligan says she expects to find more pre-Clovis sites in the future, now that her team knows those people existed.

"I expect that our understanding will change dramatically," she said.