TORONTO -- Archeologists in Norway have discovered an Iron Age cemetery deep in the earth, complete with what may be a feast hall, a cult house and a Viking ship burial -- all found without lifting a shovel.

Gjellestad in Norway is no stranger to history -- one of the largest Iron Age funerary mounds in Scandinavia, the Jell Mound, is found there. But according to new research using ground-penetrating radar (GPR), this is just the beginning.

“The site seems to have belonged to the very top echelon of the Iron Age elite of the area, and would have been a focal point for the exertion of political and social control of the region,” Lars Gustavsen, lead author of the research from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research, said in a press release.

Researchers used GPR to peer below the surface at Gjellestad in search of new archeological sites between 2016 and 2019. They were aiming initially to see if planned construction projects would disrupt any undiscovered archeological sites, since historical records suggested there could be three other funeral sites that had been demolished in the 19th century.

But the results of their GPR search, published this week in the journal Antiquity, revealed that there was even more beneath the ground than historical records showed -- enough evidence for researchers to believe this area used to be one of high political and cultural significance.

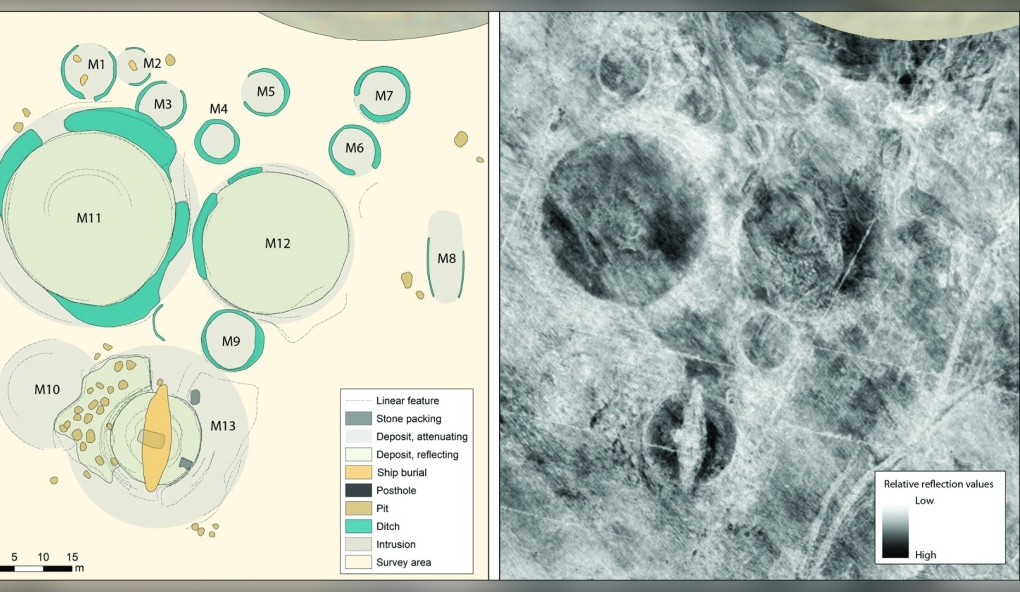

By carefully examining the GPR scans, which show numerous circular and strangely-shaped anomalies in the ground, researchers were able to hypothesize what was likely there, such as identifying the characteristic shapes of Iron Age burial mounds.

Three of the burial mounds identified in the scans were significantly larger than the others, and contained “material with highly reflective properties.” The largest of the three was approximately 30 metres in diameter, but had a maximum diameter of 39 metres due to its uneven shape.

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact dates of the burial mounds and structures discovered at Gjellestad, but researchers believe the burial mounds could have been created anywhere from the 5th to the 10th centuries CE. While the Jell Mound dates to the 5th century CE, these types of mounds were known to extend even into the Viking period.

One detail that pushes the timeline into the 10th century is something observed at one of the three large burial mounds.

This mound was bisected by a bizarre shape, which showed up on the scans as a long, diamond-shaped structure. Researchers realized it was likely a ship, approximately 19 metres in length and five metres wide. Another shape near its base could be the remains of the ship’s keel, the paper suggests.

“Such ship burials were likely reserved for powerful Viking individuals,” a press release states.

The size of the ship indicates that it would’ve been capable of travelling in the ocean, making it a rarer type of ship burial. This ship helps to show how long this region was in use and still significant, since the ship can be dated to between the 9th and 10th centuries CE.

Burial mounds were far from the only thing they found.

Researchers identified where structures such as houses could have been by finding dark pinpricks on the scans — these showed where holes dug for roof-supporting poles were.

Four houses were identifiable based on these postholes. One had two entrances to an open room approximately 50 square metres in size, with “a possible hearth.” Another house of similar size, which researchers believe is a common farmhouse, was likely an early structure at the site.

One of the buildings had an asymmetrical layout, with two rooms around 60 square metres near the centre of the structure, and a fence radiating out from the south-eastern corner. This structure, researchers say, was a “substantial building” compared to the sizes of other structures during this period.

“This, and its location overlooking the slopes of the Viksletta Plain, would have resulted in an easily recognisable marker in the landscape, one clearly visible from the seaward approach, if not from the outer sea lanes,” the paper states.

It was likely a hall of some importance, and the presence of convex walls helped to date it to the Late Nordic Iron Age, researchers said.

A final structure, shaped unusually enough that researchers did not believe it was meant for habitation, might have been a “cult house,” which had religious significance, and would help to mark this region as one that had cultural significance at the time as a “central place.”

“The cemetery at Gjellestad appears to have been long-lived, and the size of its mounds, their juxtaposition with potentially high-status buildings and the presence of grandiose burial rites all point to Gjellestad being a site of some importance in the Late Iron Age,” the paper states.

Its long history of use, ranging from more ordinary burial mounds to extravagant ship burials, indicates it could span a wide swath of Scandinavian history, the press release claimed, going from the “political turmoil following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire to the rise of the Vikings.”

“It forms a stepping stone for further research into the development and character of social, political, religious, and economic structures in this tumultuous period,” Gustavsen said.

That research is already underway; an excavation of the ship burial is currently being held. It is the first time in almost 100 years that a Viking ship burial has been excavated, meaning modern technology will be able to shine new light on the past.