TORONTO -- Stargazers everywhere are concerned about the ongoing launch of tens of thousands of new satellites into low Earth orbit, warning that they threaten the view of the night sky.

Private companies including SpaceX, Amazon and others have been launching thousands of these new mini-satellites, mostly for wider broadband internet coverage on the ground.

The launch of these so-called satellite constellations have been increasing significantly in recent years, according to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which aims to promote and safeguard astronomy.

“Until this year (2019), the number of such satellites was below 200, but that number is now increasing rapidly, with plans to deploy potentially tens of thousands of them,” the union said in a statement last year.

“In that event, satellite constellations will soon outnumber all previously launched satellites.”

WHAT ARE THE CONCERNS?

The union’s concerns centre on two points. Firstly, the reflective surface of these satellites interferes with telescopes.

Last month, SpaceX launched 60 more mini internet satellites to join 120 launched last year, but this time testing a dark coating to appease stargazers.

“At the moment it is difficult to predict how many of the illuminated satellites will be visible to the naked eye, because of uncertainties in their actual reflectivity,” the IAU said in its February findings on satellite constellations.

“The appearance of the pristine night sky, particularly when observed from dark sites, will nevertheless be altered, because the new satellites could be significantly brighter than existing orbiting man-made objects.”

There are no internationally agreed rules on the brightness of satellites, the IAU said.

Its second concern is the radio signals that satellites emit, which they say interfere with radio astronomy.

“Recent advances in radio astronomy, such as producing the first image of a black hole or understanding more about the formation of planetary systems, were only possible through concerted efforts in safeguarding the radio sky from interference,” the IAU wrote.

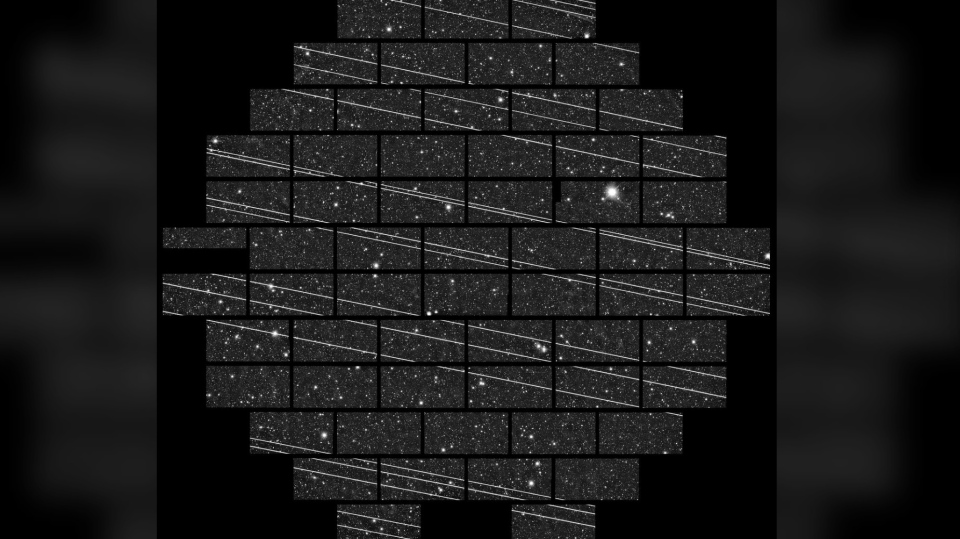

Light pollution has been an ongoing problem for stargazers and now moving satellites are creating long lines of light in pictures collected by astronomers.

“The prominent trains of satellites (strings of pearls)… are significant immediately after launch and during the orbit-raising phase when they are considerably brighter than they are at their operational altitude and orientation,” the IAU said in its findings.

“Apart from their naked-eye visibility, it is estimated that the trails of the constellation satellites will be bright enough to saturate modern detectors on large telescopes. Wide-field scientific astronomical observations will therefore be severely affected.”

‘A CURTAIN OF BRIGHT LIGHTS’

Noted Canadian astronomer Paul Delaney, a professor at York University in Toronto, agreed the IAU’s concerns were justified.

He said since the beginning of the space age in 1957, about 10,000 satellites have been launched and most of them remain in Earth’s orbit.

“From the professional astronomer’s perspective we’re looking to literally the edges of the universe, so we have big powerful instruments that are trying to eke-out the faint detail which is out there,” he told CTV’s Your Morning.

“When we put literally a curtain of bright lights in front of that very faint distant source, then you are compromising the type of observations we can make. They’re moving across our field of view very quickly and they are quite bright compared to the stars behind them.”

Delaney explained that private companies, like SpaceX and Amazon, are regulated for the launching of satellites.

“But to the best of my knowledge there is very little commentary about how many satellites they can put and where they can put them,” he said.

“That’s where human space tourism is going to be residing in the not very distant future.”

He explained that “relatively flimsy” satellites burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere within 10 to 15 years.

“Let’s sit down and before we put up tens of thousands, let’s make sure we know the characteristics of these satellites,” he said.

“Do we need 20,000, 30,000? Perhaps we can get away with 10,000,perhaps we can get away with 5,000. I don’t think there’s been a lot of thought put into mitigating the problem and therefore talking with all the stakeholders.”

The IAU and the American Astronomical Society (AAS) said it will continue to speak with space agencies and private companies in order to mitigate the impact constellations may have in interfering with astronomical observations.