OTTAWA - A quarter-century after the worst terrorist attack in Canadian history, a federal inquiry is set to deliver a belated verdict on what went wrong -- and what can be done to ensure that another such tragedy never takes place.

The report on the 1985 Air India bombing, expected to be presented to Prime Minister Stephen Harper and made public Thursday, is the product of nearly four years of work by former Supreme Court justice John Major and a staff of lawyers and researchers.

The team sifted through tens of thousands of pages of classified documents and took testimony from more than 200 witnesses during the painstaking investigation.

The five volumes will total nearly 4,000 pages of historical narrative, factual findings by Major on long-disputed points and recommendations for policy reforms to improve police work, intelligence operations, airline security and the conduct of anti-terrorist trials by prosecutors and judges.

And still it may not be the final word.

"This event is so perplexing, so multi-faceted, there are so many layers, it has been so long," says a source familiar with the report.

"I don't think, with this kind of event, the door ever really closes -- it's just like 9-11. But at least the historical record of the involvement by government agencies has been thoroughly canvassed, and for the first time (they are) being brought to account."

Air India Flight 182, bound from Toronto and Montreal to New Delhi, was brought down over the Irish Sea on June 23, 1985, by a terrorist bomb stowed in the luggage compartment. There were no survivors among the 329 people on board, most of them Canadian citizens of Indian origin.

Another two people perished the same day when a second bomb went off in baggage being transferred to another Air India flight in Narita, Japan.

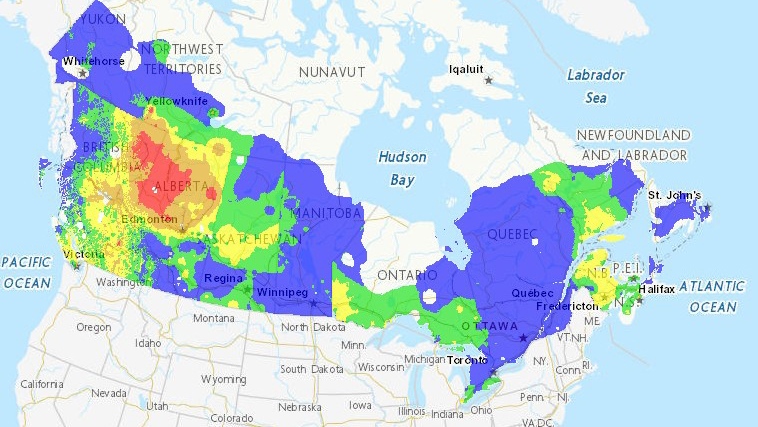

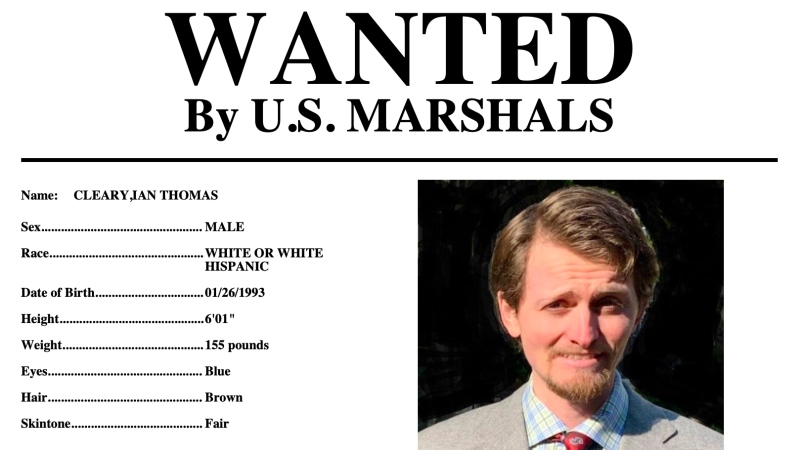

Both attacks were blamed on Sikh militants based in British Columbia, but only one man has ever been convicted on a reduced charge of manslaughter. The suspected ringleader of the plot, Talwinder Singh Parmar, was arrested but freed for lack of evidence and left Canada for India, where he was shot dead by police in the Punjab in 1992.

Two other men were acquitted at trial in Vancouver in 2005, in a judgment that outraged the families of the bombing victims and helped lead to the Major inquiry.

The tortuous course of events has understandably frustrated the victims' families, most of whom hope that Major's report will serve as at least one step toward emotional closure. For others, however, the wait has already been too long.

"Sadly, for some, it's been an eternity," says Jacques Shore, a lawyer representing the families.

"It is tragic to recognize that some of these family members did not live to see the day the report will come out. They, too, must be remembered, because they as well were victims of this terrorist act."

In their testimony before Major, a succession of family members relived their harrowing experiences -- some recalling how they couldn't stop crying, others how they could no longer cry at all, still others explaining how they had changed jobs, sold houses, even moved to new countries in a vain effort to extinguish their grief.

Few received psychological counselling, and when they did it was usually at their own expense. Compensation paid by the Canadian government varied widely and often didn't come at all without prolonged haggling.

Other testimony by current and former members of the RCMP and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service painted a picture of strained relations between the two agencies, with key wiretap tapes erased, important leads left to grow cold, investigators quitting in frustration and crucial witnesses reluctant to co-operate because they feared for their lives.

Air transport experts recounted security shortcomings by Air India, as well as by Canadian airport authorities and regulators, while financial analysts deplored a lack of co-ordination that still hasn't been fully remedied in the tracking of money raised by terrorist front groups.

Shore and co-counsel Norm Boxall, in their closing submissions, called on Major to deliver a finding of "intelligence failure" by CSIS for not heading off the bombing, as well as "institutional failure" by the RCMP and Transport Canada and "corporate failure" by Air India in its security arrangements.

The lawyers maintained the victims' families are owed a formal apology and a fresh look at potential monetary compensation -- even though Major's mandate technically precludes him from assessing criminal or civil liability.

Government counsel, for their part, insisted there was no point in laying blame for past mistakes and urged the judge to concentrate on recommendations that would improve things in future. They made no effort to offer their own guidelines for reform, saying the government preferred to wait and see what Major concludes.

The judge started taking public testimony in the fall of 2006 and wrapped up hearings in February 2008. But federal officials later handed over thousands of pages of additional documents, complicating the drafting of a final report.

Major signed off on the finished product in mid-2009, but it took until the end of the year for the government to vet the report to ensure no information deemed injurious to national security would be publicly disclosed.

It took another six months after that to translate the full report into French and arrange for layout, printing and other production work.

Federal spending estimates show $22.6 million was earmarked for the inquiry budget during its first three years of operation, plus another $6.1 million for various government departments involved in the probe. That brought the total bill to taxpayers to $28.7 million as of March 2009; a final tally has yet to be released.