OTTAWA -- The RCMP has rolled out mandatory conflict de-escalation training to respond to concerns about their officers' use of force.

The force says crisis intervention and de-escalation has always been part of its training, but they've now carved it out as a specific three-hour online course delivered to all new recruits at Depot, the RCMP training academy. The online training is based on a de-escalation course used by police forces in British Columbia, which the RCMP adapted to be used across the country. It's been in place since September, and all officers have to take it by next fall.

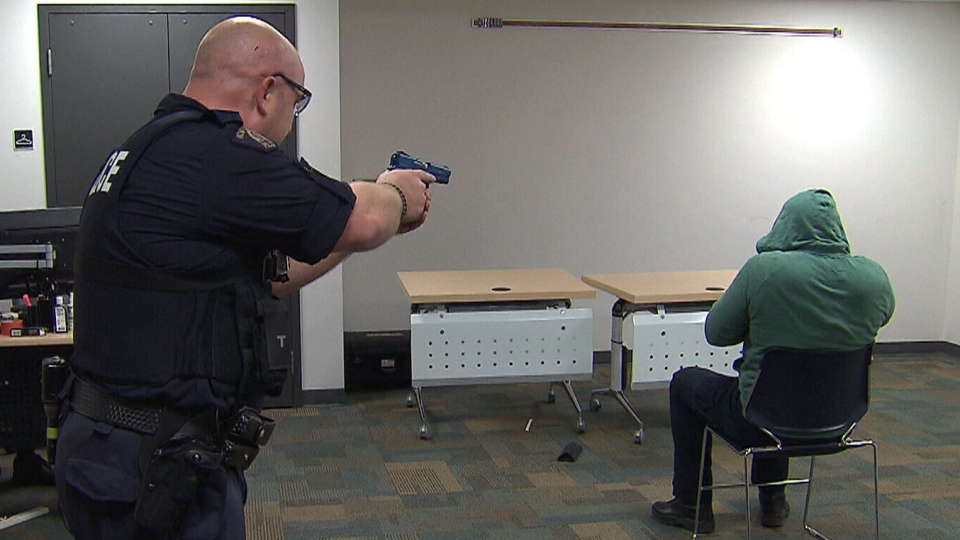

The RCMP invited CTV News to preview a summary of its de-escalation training, as well as an abbreviated form of its existing incident management intervention model, or IMIM.

The training comes amid controversy in the U.S. over use of force against unarmed African Americans, and lingering concerns in Canada following a 2007 incident at the Vancouver airport in which the RCMP used a Taser on Robert Dziekanski, who died.

"The accountability of what a police officer might do or not do - that scrutiny is very high now," said Chief Supt. Eric Stubbs, who heads up the national criminal operations division, in an interview with CTV News.

"We have to give them as many tools as we can and [as] many techniques as we can to try to resolve that situation without them getting hurt, without the public getting hurt and of course the person, the client that we're dealing with."

The training teaches officers to communicate with emotionally distressed people, and focuses on subduing the crisis without violence.

'They need a lot more'

Françoise Drouin-Soucy, a training program manager with the Canadian Mental Health Association, reviewed the new online course before the RCMP introduced it.

She says it's thorough and a good step for the national police force, but added that she and the colleague who looked at it made it clear that the course can't be a standalone product.

"If that's all they get, then for sure that's a little bit limited and I think we were pretty honest about that with them," Drouin-Soucy told CTVNews.ca.

She says it's encouraging that the RCMP say they emphasize de-escalation throughout their training -- not just in this course -- and noted their role is challenging.

"The police force gets called in because it's beyond what most other people can handle," Drouin-Soucy said. So the training has to balance that reality with the need to distinguish between someone in acute distress and someone who poses a threat.

Drouin-Soucy isn't the only one with concerns about the course's brevity. Marney Mutch, whose son was killed in 2014 by police in Victoria, says an online course is too little and too ineffective. Officers said Mutch's son Rhett had a knife and rushed them. An inquiry into the shooting said their use of force was justified.

The Victoria officers received the same training the RCMP is introducing prior to the incident.

"They need a lot more involved training," Mutch said.

"It's a start, but I think to move in the right direction, I think absolutely more time needs to be devoted [to] more practical exercises."

Stubbs said one issue the force is dealing with is an increase in mental health calls. The training, he hopes, will help RCMP officers "better handle that type of call" when it comes in.

"You have to be able to talk to people, you have to be able to bond with them in a moment of crisis," Stubbs said.

The question is whether trainees can learn that skill in three hours.

Rob Gordon, a criminology professor at Simon Fraser University, says he has grave concerns about using online training for almost anything. Gordon says while it's difficult and costly for the RCMP to retrain members based across Canada, the Mounties need ongoing training to refresh the conflict intervention and de-escalation lessons.

"It's not one-shot training and education. It has to be reasonably continuous. Otherwise it's quickly forgotten - and especially if it's not put into practice in any way," Gordon said.

De-escalation training is extremely valuable, he said - if it's done properly.

"If it's not, then obviously it's not going to have the desired effect."

The role-playing scenarios done as part of every officer's regular retraining is a more effective way of teaching, Gordon added.

Mutch says she's concerned that people the RCMP are dealing with aren't the only ones dealing with mental health issues.

"We have officers that have [post-traumatic stress disorder] that is undiagnosed, and justifiably so because of the type of work and what they're seeing.... So it's time that we turn the mental health lens to also focus on them, because it's not just the citizens that have the problem there."

'No force looks good'

Stubbs said there are no numbers on how often de-escalation techniques are used simply because officers employ them multiple times a day.

The officers who lead the training are clear: 99.9 per cent of the Mounties' two million calls every year are resolved without force. Their ability to communicate is their most important skill.

"In everyday life, we always de-escalate. We always use communication as a first option," said Steve Oster, who is one of the RCMP's use of force instructors.

"But you're not going to be able to de-escalate every single time. And that's when we decide what force we're going to use to resolve the situation."

Ensuring officers listen to subjects isn't the only communication the trainers are worried about. Being able to explain themselves to the media and investigators probing use of force is another concern for officers, whose primary concern is keeping themselves safe so they're in a position to protect others.

"No force looks good. You'll never watch a video and say that's great use of force. It never looks good and it's not supposed to look good," Oster said.

"You have to hear [the officer's] side of the story," he added.

"That's part of the training that we've gone through...so they can properly articulate and transfer to somebody why they did what they did, to help you understand."

Deadly shootings rare

A spokesman for the RCMP says there are an average 2,800 uses of force out of 2.7 million calls every year, according to the Mounties' records. That's 0.1 per cent, or one in 965. Deadly RCMP shootings are incredibly rare, with officers shooting to death a subject once in every 407,830 calls, or 0.0002 per cent of calls.

Asked for more details about use of force, the RCMP didn't provide specifics to CTV News. CBC News reported last month that RCMP use-of-force complaints have dropped significantly since 2010, from 22 that year to 8 in 2015. The numbers came out of an access to information request.

There are also no official national statistics on fatal police shootings in Canada. A group of researchers maintains a list on a website called The Reported, counting them based on media reports and information released by law enforcement agencies.

The Reported says 36 people were killed by police - whether local, provincial or national - this year. That's one more than in 2015 (in a 37th case, it's not clear whether the deadly gunshot was self-inflicted or delivered by police, according to the website).

Insp. Adam MacNeill, who works with the Mounties' National Emergency Response Program, says officers who shoot somebody carry it with them for the rest of their lives.

If officers can talk a person down, MacNeill says, "then that's a win for the police."

The RCMP is researching how officers' body chemistry affects their responses in crisis situations. They know that running simulations helps trainees understand, and possibly adapt, to how their bodies react when faced with a real-life scenario.

"Obviously these decisions are split-second decisions," MacNeill said.

"There are certain physiological and psychological responses that members have when they're involved in a use-of-force incident that affect their performance... we're trying to teach them to manage things like the hormonal dump from their brain, adrenaline, other hormones that are released during these types of confrontations."

"Even when you do everything right, you're not necessarily going to be able to avoid a use of force outcome," MacNeill said.

"But of course that's our goal. The police don't relish using force on anyone."

With files from CTV National News' Parliamentary Correspondent Kevin Gallagher