EDMONTON -- Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole reopened the debate surrounding the Safe Third Country Agreement this week, promising voters in Quebec that he would close the border at Roxham Road, a popular entry point for asylum-seekers.

The issue is one that former Conservative leader Andrew Scheer campaigned on in 2019, when he too pledged to shut down what he described as a legal “loophole” enabling tens of thousands of asylum-seekers to cross the U.S. border into Canada and claim refugee status.

But experts say O’Toole’s pledge is complicated and misleading.

THE CLAIM

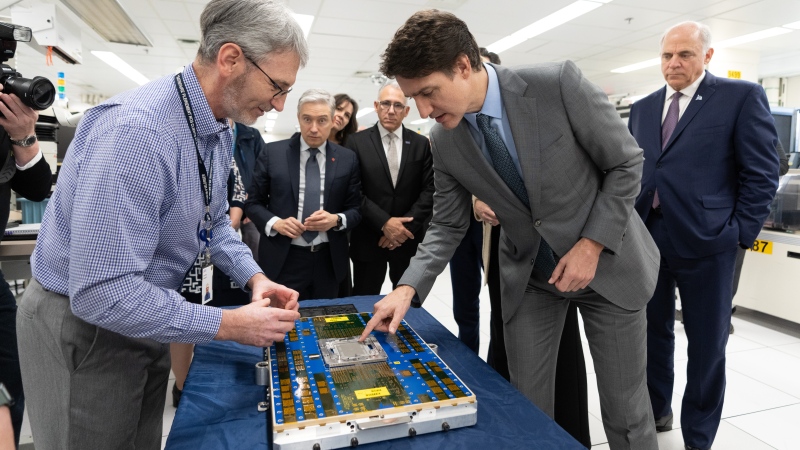

In a video posted to his Twitter account Monday, O’Toole said in French, “With Justin Trudeau, thousands of people crossed the border illegally. This system is unjust for the families that follow the rules and wait their turn.” The caption of the video says that, if elected, his government would “close the border at Roxham Road once and for all.”

“I’m proposing a welcoming country that respects its borders,” O’Toole goes on to say in the video, which was posted in French only. “All immigrants can settle in Quebec, in Canada, to work, to study, or to start a family, but in a legal way that respects the laws of the country they want to immigrate to.”

In his platform, O'Toole is also promising to create a "joint border patrol" with the U.S. at and near high-traffic points on the border to stop asylum-seekers from entering Canada.

ANALYSIS

In recent years, Roxham Road has been a popular entry point for asylum-seekers, where southern Quebec meets the state of New York at a dead-end road. Because the site is between an official port of entry, it is considered an informal crossing point.

And while you would not be allowed to cross the border at Roxham Road for tourism purposes, advocates say asylum-seekers who cross the border through informal crossing points have legal protection under Canadian law to have their refugee claims heard by immigration authorities.

“There is nothing in the immigration law that indicates it's unlawful to arrive at the border between a port of entry for the purpose of seeking refugee protection,” refugee and immigration lawyer Maureen Silcoff told CTVNews.ca by phone Thursday.

“Canada has certain international legal obligations, based on the 1951 Refugee Convention, to allow someone who arrives at the border to present their protection needs. And then Canada must assess whether somebody meets the criteria to be a refugee.”

These legal protections were established in 1985, after the Supreme Court ruled that asylum seekers should have the protection of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the federal government should hear their claims.

Silcoff added that O’Toole’s statement appears to suggest there is only one line for people seeking to enter Canada for immigration purposes.

“Historically, our laws and policies have distinguished between immigrants and refugees,” she explained, noting that an immigrant is someone who comes to Canada for the purpose of family reunification, to work in a particular field, or to be an international student.

Refugees, on the other hand, arrive at our border claiming protection from things like war or political strife in their home country.

“When someone does arrive in Canada immediately they're checked for security issues, for criminality right at the beginning. And in addition, there is a tribunal, the Immigration and Refugee Board, that is mandated to hear someone's refugee claim and determine whether they meet the criteria,” she said.

“That's a robust process that somebody has to go through in order to satisfy a tribunal member that they are in fact a refugee according to Canada's laws.”

In 2019, the RCMP stopped 16,503 people as they came into Canada from the U.S. using informal entry points like Roxham Road, down from 19,419 in 2018, and 20,593 in 2017.

Those numbers have dropped even further over the last year thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, asylum-seekers have been turned around at the border since March 2020 due to public health measures.

But promises to close informal border crossings go beyond the question of legality. Experts say O'Toole's proposal won't solve the issue because of the Safe Third Country Agreement between Canada and the U.S.

“The U.S. has not agreed to take back refugee claimants in between ports of entry – these crossings are not covered by the Safe Third Country Agreement,” Janet Dench, executive director of the Canadian Council for Refugees, told CTVNews.ca by email.

The agreement means that those arriving in Canada from the U.S. through a legal port of entry are not eligible to make asylum claims because they must seek refugee status in the first "safe country" they pass through.

However, the agreement does not apply to irregular border crossings, which means Canada cannot deport refugee claimants before hearing their claim.

“Canada cannot unilaterally extend the Safe Third Country Agreement, and there is no indication that the U.S. government is willing to extend the agreement,” Dench said, presuming O'Toole means he wants to extend the Safe Third Country Agreement so it applies between ports of entry.

The Liberals have also fought to “modernize” the agreement.

In July 2020, the Federal Court declared the Safe Third Country Agreement unconstitutional, saying it violated “the right to life, liberty and security of the person,” as guaranteed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Trudeau government appealed that decision and won in April. Refugee claimants and their advocates are now asking the Supreme Court of Canada to review the decision.

CONCLUSION

Advocates like Silcoff and Dench say its misleading to say migrants crossing at Roxham Road are doing so illegally.

O’Toole’s promise to close irregular border crossings requires much more context, thanks to the fine print surrounding the Safe Third Country Agreement.

Edited by Ryan Flanagan

- With files from The Canadian Press