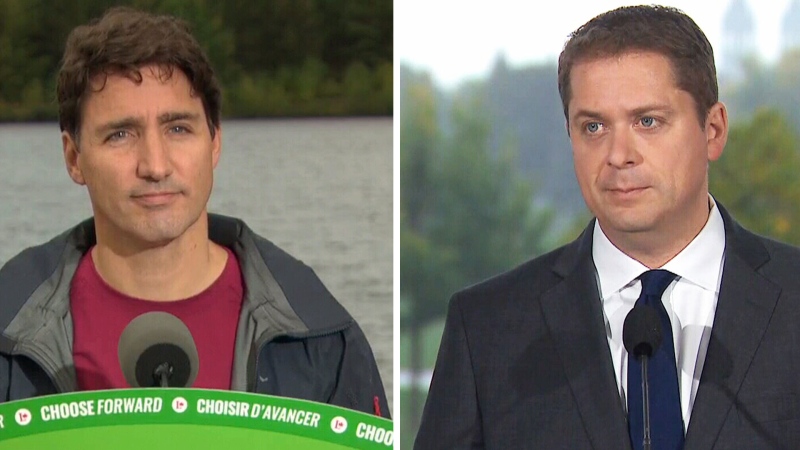

TORONTO -- Drowned out by the cross-talk of Monday’s leaders’ debate was an accusation that Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau seemed to have no response to.

Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer hit him with it twice.

“[Trudeau] has granted a massive exemption to the country's largest emitters,” Scheer said about 30 minutes into the debate.

“You have given a massive exemption to the country’s largest polluters,” he later said again to the Liberal leader.

NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh also repeated the claim that Trudeau’s Liberals are currently granting a carbon tax exemption to the country’s big polluters.

While Trudeau seemed to have no counterpoint, some climate policy experts are taking issue with the claim. They say no, there is no “exemption” for big polluters — but explaining the system is more complicated.

How does the carbon tax work?

“The important thing about the Trudeau carbon pricing plan is that there are two separate systems: one for regular consumers of fuels and one for big polluters,” says George Hoberg, who specializes in environmental and natural resource policy at the University of British Columbia.

To simplify the first system, regular consumers and small businesses pay a carbon tax on fuels, and households get money back in the form of a rebate based on their income. But the carbon tax is applied differently for industry.

“The system for big polluters is actually quite complex,” Hoberg says. “It taxes big polluters at the same rate as regular consumers but then returns to them an ‘output-based subsidy’ that is either 80 per cent or 90 per cent of the amount that they pay.”

To determine how much carbon tax a business will pay, the government first looks at the average emissions intensity across the industry. In general, the business will be given emissions credits equal to 80 per cent of whatever that average rate is (for a few specific industries, that rate is 90 per cent).

Jennifer Winter, the director of energy and environmental policy at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, lays out an example.

Let’s say a business produces widgets, and that across the sector, the average carbon emissions intensity is 420 tonnes per widget. That business will receive a credit for 80 per cent of 420 tonnes for every widget it produces, regardless of how many emissions it actually puts out per widget.

So if the business produces 10 widgets per year, it will receive a credit for 0.8 x 420 x 10 = 3,360 tonnes of emissions.

If it’s an average business that does indeed emit 420 tonnes per widget, it’ll pay a tax on the 4,200 tonnes it emits, and get a credit back on the 3,360 tonnes it’s allowed.

In total, at the current carbon tax rate of $20 per tonne, that would amount to a cost of $16,800 for this particular business.

Ultimately, a company that produces above that emissions intensity rate will pay more in carbon taxes than it receives in subsidies -- but a business that can get below that rate would actually receive more in subsidies than it pays out.

So while no businesses are “exempt” from the carbon tax rules, no business would ever end up paying 100 per cent of the tax after rebates – and the relatively efficient businesses receive rebates that cover the cost of those taxes entirely, meaning they would effectively pay no carbon tax.

Some “big polluters” will end up with no net cost, or even profit from the carbon tax — but that’s by design, says Winter.

“The assumption is, the large emitters that are trade exposed, they export a lot or compete with other firms that import into Canada,” she says. “They don’t have any ability to adjust their prices.”

If local businesses are subjected to a flat-rate carbon tax, in theory they could just raise prices accordingly, passing some or all of that cost on to consumers. Since their local competitors face the same tax, they would have to raise their prices as well.

But a Canadian business competing on the global market can’t simply raise prices, says Winter, because international competitors might not be subject to those same taxes.

And the worry is that taxing those specific industries without rebates wouldn’t encourage a reduction in emissions – it would encourage businesses to relocate to another country. That’s referred to as “carbon leakage,” and it means a loss for Canada without a gain for the environment, says Winter.

“There’s unlikely to be a reduction in emissions globally that corresponds with the decrease in economic activity in Canada,” says Winter. “So that means we’ve penalized ourselves.

How do the Conservatives and NDP compare?

The NDP platform says the party will keep the Liberal carbon tax in place, but “roll back” the subsidy to polluters – though it’s unclear to what extent.

“I’m assuming that means they want to reduce or eliminate altogether the rebates returned to big polluters,” Hoberg says. “What they don’t say is how they will keep those industries in Canada, which the Trudeau government instrument is designed to do.”

Andrew Scheer’s Conservatives say they’ll get rid of the carbon tax but still force businesses that exceed unspecified limits to pay into a green technology fund.

“That I would characterize as actually giving firms an exemption,” Winter says. “Firms would be able to emit up to a certain amount at no charge, and then above that amount they would face that levy or investment requirement at whatever dollar per ton amount.”

Read More

Read more about the output-based pricing system here and here.

Read more about the Liberal carbon tax here.

Find the Conservative climate plan here.

Find the NDP climate plan here.