OTTAWA -- From do-or-die votes to opposition-dominated committees, the 43rd Parliament is going to work differently under a minority government. But, given the ideological split between the major opposition parties, the Liberals will have stronger footing, say experts.

To get a sense of what kind of shakeup is coming to the House of Commons, CTVNews.ca spoke with procedural experts and people who have been part of House leadership teams in hung parliaments.

In general the Liberals will have to consult in a more meaningful way, and constantly find compromises with the other parties. Factoring in where they may be able to find support, or will face pushback, will need to be done on every item of government business they look to advance.

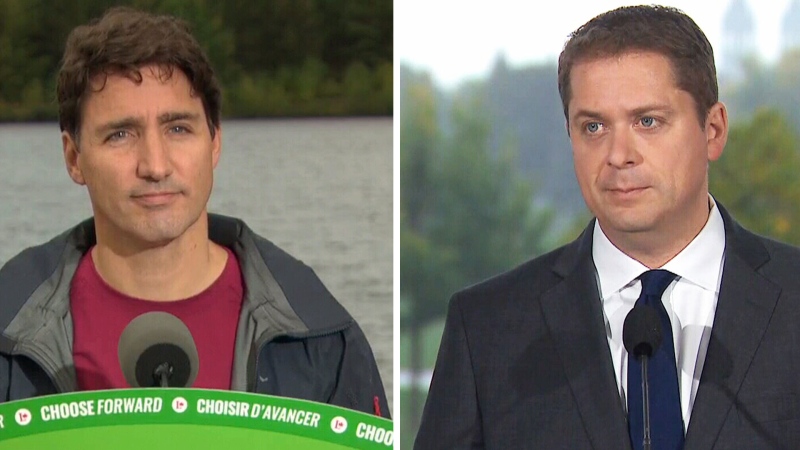

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledged this in his post-election news conference at the National Press Theatre on Wednesday, when he spelled out how the next few weeks and months will look. Trudeau said Canadians sent the Liberals back with a clear mandate but also a “clear requirement” to work with other parties.

And, he squashed speculation that the Liberals would form a coalition -- formal or not -- with other progressive parties. This is not surprising, given the relatively stable minority situation they find themselves in. Just 13 seats shy of a majority, they will have some flexibility in where they find alliances on a vote-by-vote basis. They will also have the flexibility to look to different caucuses on certain issues.

“His opposition is divided in the sense that they're on different parts of the spectrum,” said Peter Van Loan, who held the role as Conservative House leader through both minority and majority parliaments.

“I think because of the divided parliament and the strength that they're in, it has the potential to be one of those four-year minorities,” Van Loan said. While most minority parliaments last on average about two years, a four-year minority government did happen in Ontario, from 1977 to 1981, under Bill Davis.

Say the Liberals want to pass measures for the energy sector as a way to address the rift with the two western provinces they were shut out of electorally, the 121-member Conservative caucus that holds all but one seat in the region may provide enough votes to pass it.

If pharmacare or further climate change targeted measures are taken, the 24 NDP MPs could give enough support to pass those initiatives. And, it’s possible that should calls for more transparency around the SNC-Lavalin scandal resurface, the Bloc Quebecois caucus of 32 might be interested in siding with the Liberals. If they were to do so in the spirit of protecting the Quebec-based company, the Liberals would have enough support to outvote the Conservatives and NDP, which have united against the government in the past on ethical matters.

“It is in the highly stable category,” Paul Thomas, senior research associate at the Samara Centre for Democracy of the Liberal majority, told CTV’s Power Play on Wednesday.

Even with Trudeau saying he intends to sit down with all party leaders to establish on what issues common ground can be found in the coming days, in many ways the opposition will still find themselves in the driver’s seat. While some have sat in minority parliaments in the past, many MPs heading to Ottawa have not, so be sure that members of each caucus are already at work reading up on parliamentary procedure. And, whoever is named to be the House leaders and whips for each caucus will play pivotal roles, as will their staff.

1. Confidence votes and passing bills

Any government stays in power between fixed election dates so long as they can maintain the confidence of the House of Commons. This is what the Liberals will have tested and need to survive in the coming months.

As former House of Commons law clerk Rob Walsh has said, if Trudeau passes a confidence bill, “he does, he carries on as government; if he doesn’t, he’s out.”

In general there are a few bills or motions that are always considered confidence matters: the Throne Speech, budget bills, and any supply bills like the estimates.

But beyond that, those with first-hand experience who CTVNews.ca spoke with said the government has the discretion to determine what wouldn’t, or would be, a confidence vote.

“What you can get away with sometimes depends on public opinion,” said Van Loan.

One thing to expect to see less of: time allocation and closure motions meant to limit the amount of time there is to debate government legislation.

While not confidence votes, with every vote being a negotiation for support with constant backroom bartering, the government will have to pick its battles.

“The mindset is completely different,” said Semhar Tekeste, a senior public affairs consultant at Enterprise Canada, who worked in the whips office through the last two Conservative governments.

“You’ve got to figure out, you know, where are your votes? What is the opposition thinking? There’s a lot more work across the aisle,” she said.

2. House of Commons committees

One of the aspects of Parliament Hill life that will change the most is the dynamics around House of Commons committee tables. Before the new session gets rolling, the experts CTVNews.ca spoke with said to expect all parties to get together and negotiate the makeup of committees, but one big change will be that opposition parties hold the majority of seats.

What does that mean? Think about the studies, calls for documents, or requests for high-profile people to testify that were defeated by the Liberal majority in the last Parliament. In this new Parliament, opposition members have new powers to compel these kinds of things from the government.

“That dynamic means that the opposition gets to set the agenda of the studies of the special inquiries into whatever corruption is going on and so on, where they can create a lot of mischief,” Van Loan said. He speculated that the breakdown of seats around the committee table might look something like: five Liberals, four Conservatives, one Bloc Quebecois MP and one NDP MP. The distribution is intended to be proportional to the number of seats each party has.

“We're in a situation where anything is possible, anything can be negotiated, right? Committees are the masters of their own domain,” said Tekeste.

Because of the newly unpredictable nature of committees, Thomas wonders whether a shift in lobbying similar to that seen in the last Parliament -- away from MPs and towards Senators because of the increasing number of “Independents” -- could mean committee members and opposition critics getting more attention from advocacy groups, lobbyists and others looking to alter government legislation.

As well, yet to be seen is what happens with the role of parliamentary secretaries. The Liberals may have tied their own hands by changing the House of Commons rules in the last Parliament to make it so that parliamentary secretaries are not allowed to be voting members on House committees. Despite this, parliamentary secretaries often do sit in on meetings and report back to their minister on what’s being said.

“I would not be surprised if they reneged on that,” said Van Loan.

3. MPs Housebound, limited travel

Minority parliaments are in many ways a numbers game and the whips will have to keep a close eye on the number of MPs they have on-hand. This will mean a few things for MPs and ministers: less travel and more House time.

“Backbenchers are going to be immensely frustrated with the inability to go home,” said Van Loan, who said there will likely be more discipline for who is able to skip out early in the evenings, or travel home on Fridays for those in faraway constituencies.

And, should MPs or ministers be heading out of town, expect a few more opposition members to accompany them -- it’s called pairing, Tekeste said.

“The parties will work together to ensure that the votes don't get lost. So if the government needs to send them a minister somewhere, they'll get another member of an opposition party to pair with them so that the numbers remain even,” she said.

4. Constant threat of another election

Compounding all this is the reality that the next election could be just around the corner and that puts every party in a constant campaigning mode.

“You’ll see opposition leaders say that they’re willing to go to the wall over almost every issue, but really they need time to rebuild their finances,” said Thomas.

And, on certain big bills, the government will likely look to posture as if they are ready to take the issue to the polls should the vote not go their way.

In the case of the last minority Parliament, Stephen Harper’s Conservatives didn’t have a natural “dancing partner,” as Van Loan put it, so instead they used the public as their prop-up, pushing bills they thought would be popular with Canadians.

“That's what you have to consider, right? When you're bringing forward a bill and you're facing potential defeat, are you willing to have an election where that is the issue?” said Van Loan, offering the 2008 minority government vote on extending the Afghan mission as an example.

Plus with the prospect of leadership shakeups, or at the very least leadership reviews, including for Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer, it’s yet to be seen whether any party really has the appetite to head back out on the hustings right away.

While Scheer has positioned himself as a ready leader of a government-in-waiting, the Conservatives will have to weigh triggering an election against voting in favour of issues their constituents may support. And for NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh it’s likely his party will see any time they’re able to advance progressive policy as a win.

Van Loan also speculated that the Liberals may look to put forward issues that would serve as wedges for the opposition parties. In the case of the Conservatives, that could be issues like the discussed adjustments to the physician-assisted dying law that may put pressure and expose divisions within the caucus. Plus, in the end it could ultimately be the government that orchestrates their own dissolution of Parliament should they be ready to take it to the polls again.