Despite declining poverty figures, many lower-income Canadians still feel overlooked as the leaders of the main political parties pledge to do more for the middle class.

For those who may be homeless and relying on free meal programs, their faith in politicians has faded.

Kevin Jones suffers from a shoulder injury and says his disability cheque doesn’t cover monthly expenses.

“Trickle-down economics never trickle down this far,” he told CTV News.

According to Statistics Canada, poverty levels are going down. In 2017, 3.4 million Canadians, or 9.5 per cent of the population lived below the poverty line, down from 10.6 per cent in 2016.

StatCan measures poverty by the cost of clothing, transport, food and housing – but the latest numbers use baseline costs from 2008, when the average one-bedroom apartment in Vancouver was $880 and not the $1,300 it was last year.

And according to Leila Sarangi, a director of anti-poverty group Campaign 2000, those measures are not adjusted for areas where "we see really high levels of poverty," such as First Nations reserves.

While StatCan is updating its formula for 2020, in the meantime there are plenty of Canadians who feel politicians are not talking about them.

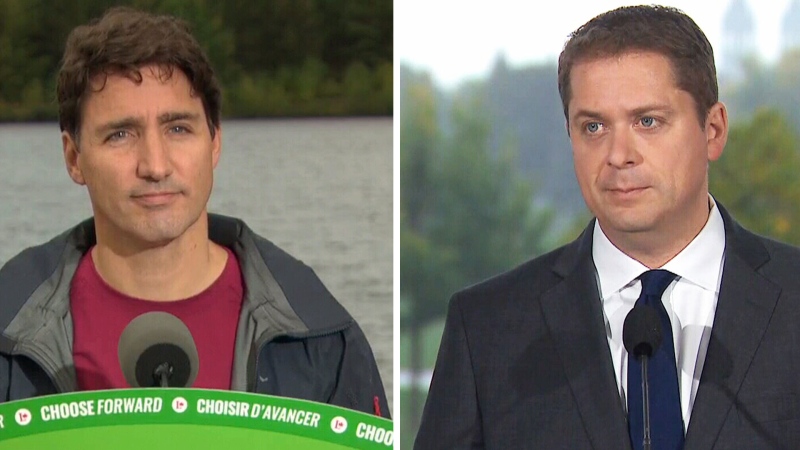

The Liberals claim to be committed to boosting the Canada Child Benefit, which they said pulled 900,000 Canadians out of poverty. But low-income housing is only promised for homeless veterans.

The Conservatives have not made a housing announcement aimed at impoverished Canadians, but they have promised to introduce a universal tax cut that they say will help struggling families.

The NDP wants to create 500,000 affordable homes and has pledged to cover dental costs for families earning less than $70,000 a year.

Rabaya Klein, who was previously homeless, now arranges group rides to polling stations and encourages others to exercise their vote.

“There’s nobody around here that’s going to be buying a house anytime soon,” Klein told CTV News.

“And so you feel like you’re not listened to.”

Meanwhile in Iqaluit, Nunavut, rent can run to more than $2,600 dollars a month and the cost of owning a home is out of reach for many in a region where numerous Inuit live on income assistance.

Some residents have been waiting more than two decades for a home and others living in cramped conditions housing as many as 17.

“We are hidden homeless people because we are not sleeping on park benches,” one resident told CTV News.

In this territory where a basic bungalow can cost more than half a million dollars, there are nearly 5,000 people waiting for public housing.

In 2017, the federal government committed $240 million to build more homes in Nunavut over the next decade, which translates to about 83 units per year.

“We estimate about 1,000 units are needed in Iqaluit right now, both private and public,” the resident added.

“And that’s growing all the time.”

Canada’s first national poverty reduction strategy was introduced last year with the goal of cutting poverty rates in half by 2030. But advocates claim that’s a bare minimum global target that a wealthy country should be far beyond already.