A gay man who was dismissed from the Canadian Armed Forces in 1994 says he has mixed feelings about the federal government’s apology to LGBTQ people who faced discrimination between the 1950s and 1990s.

Simon Thwaites was working on a naval ship when his superiors learned that he was HIV positive. Still reeling from the diagnosis, his security clearance was lowered and he was reassigned to tasks like sweeping and washing dishes.

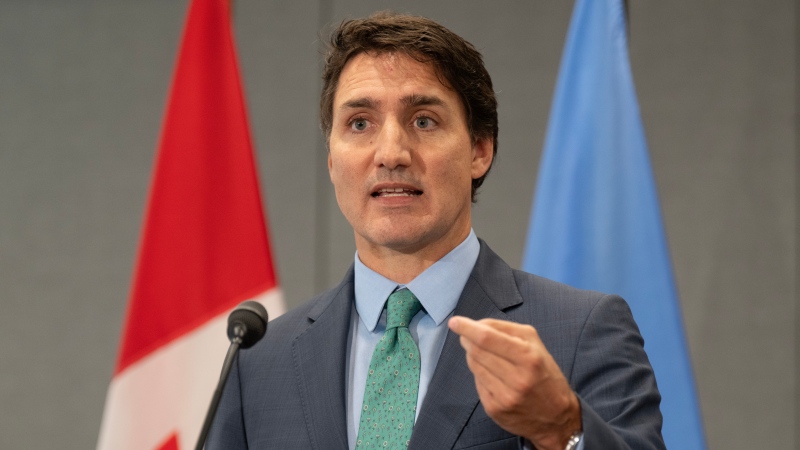

“I just got sort of pushed to the side and isolated from my peers,” he told CTV Power Play on Tuesday, after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized on behalf of the government in the House of Commons.

“My shipmates … I was told not to communicate with them,” he added.

The military issued a guideline in 1994 stating that military personnel exhibiting symptoms of HIV be categorized as medically unfit. Thwaites was honourably discharged.

He lost his medical benefits, making life with a chronic illness more difficult. He’s now part of a class-action lawsuit that the government has agreed in principle to settle for more than $100 million.

Thwaites points out that while he’s around to tell his story, many others didn’t survive -- hence his mixed feelings.

“If you look at the numbers that have applied for the class action … it’s mainly women,” he said. “There’s only a few of us guys, and that’s mainly because my peers, a lot of them, are dead.”

Thwaites says he was happy to hear Tuesday that the federal government intends to expunge criminal records like his. He also wants to know if he’ll get the pension and medical benefits that he missed out on.

Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale told Power Play that while people will need to apply to have their records expunged, there is also a process for relatives of those who have died to have names cleared posthumously.

Svend Robinson, who was Canada’s first openly gay MP, said that he was thinking about the people who died before they could witness the apology delivered by Trudeau.

“I know personally people who took their own lives just because of the shame they felt,” he said.

“It’s very important that this happened,” he added. “Many Canadians don’t have a clue about this.”

Gary Kinsman, a sociologist and activist who pushed for the apology and compensation, says Trudeau’s speech left him wanting to both “celebrate and cry at the same time.”

“This was an important part of Canadian history that most people don’t usually know about it,” he said. “It’s really important that the government has finally acknowledged it and taken responsibility for it.”

Kinsman added, however, that the apology took too long. He says people have been pushing for it since the 1990s.

“Over those decades, lots of the people who needed to be apologized to have died,” he said. “So that’s why I want to cry. This should have happened decades ago.”