WINNIPEG - Federal Justice Minister Rob Nicholson ordered a new trial Wednesday for a Manitoba man who spent 14 years in prison for the murder of a teenage girl at a rock concert.

It's the latest reversal of a conviction based on flawed hair analysis once widely used by the RCMP.

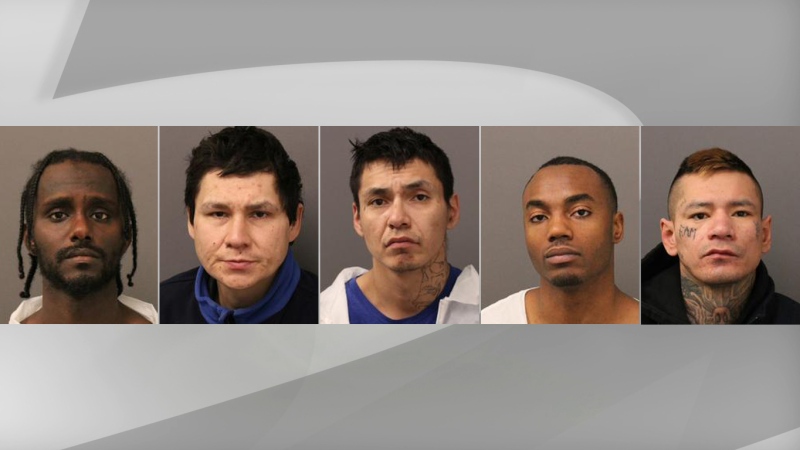

Kyle Unger was convicted of first-degree murder two years after the 1990 slaying of Brigitte Grenier, 16, at a music festival in Roseisle, Man.

"I am satisfied there is a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice likely occurred in Mr. Unger's 1992 conviction," Nicholson said in a written statement.

Unger, released on bail in 2005 while his case was reviewed, was eagerly waiting for the decision, said his lawyer, Alan Libman.

"He looks forward to a new trial, if one is necessary, to clear his name," Libman said. "He's hoping that Manitoba Justice will allow him to enter court and have an acquittal entered."

It is now up to the Manitoba prosecutions service to decide whether to proceed with a new trial. Manitoba Attorney General Dave Chomiak was not immediately available to comment.

Nicholson's decision does not imply guilt or innocence, only that an injustice occurred.

Grenier's body was found in a creek not far from the festival site. She had been mutilated and sexually assaulted.

Unger was convicted partly because an RCMP forensics expert testified that a hair found on the victim's clothing came from him. Years later, DNA testing proved the hair came from someone else.

Similar hair evidence was also used to convict another Manitoba man, James Driskell, in the 1990 death of Perry Dean Harder. An RCMP expert testified three hairs found in Driskell's van belonged to Harder, but DNA tests later revealed they actually came from three different people -- none of whom were Harder. Driskell spent 12 years behind bars before being freed in 2003.

The Manitoba government set up a review committee in 2004 to look at cases where hair analysis was used to secure convictions on murder and other serious charges.

Unger, who was backed by the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, always maintained his innocence.

But his appeal to the Manitoba Court of Appeal was rejected and leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was denied.

He was 19 when he and Timothy Houlahan, 17, were convicted in Grenier's murder.

Houlahan's conviction was ultimately overturned on appeal but he committed suicide in 1994 before a new trial could be convened.

Unger said he interpreted the suicide as a form of confession by Houlahan, and it inspired a renewed effort to dig deeper into the case and prove his innocence.

Unger had confessed to undercover RCMP officers, but the confession was considered as possibly false.

The statement was taken by police after Unger's charges had been originally stayed for lack of evidence. The RCMP officers, posing as members of a criminal organization, offered Unger money and employment if he confessed to the murder.

Libman said the wrongfully convicted association believes Unger lied when he confessed to Grenier's murder to impress the undercover officers.

He said Unger's description of the murder was fraught with significant factual errors -- a hallmark of false confessions.

Gisli Gudjonsson, considered the world's foremost expert in false confessions, accepted a retainer to study case files and Unger's confession.

Gudjonsson, a professor of forensic psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry, in London, England, has said anyone can give a false confession given the right circumstances.