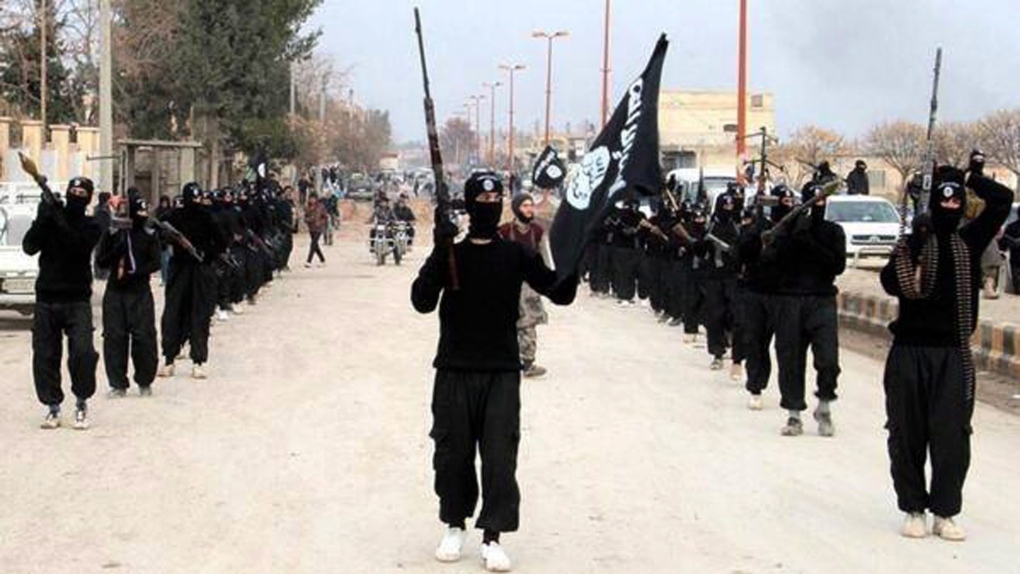

Five months after Shayma Senouci left Quebec to join Islamic State fighters (ISIS) in Syria, she wrote a long email to her friends back home. She told them that she felt she didn’t belong in the West and that she had an obligation to emigrate to a Muslim country.

“I left because I felt imprisoned in this country, I felt dirty and deadly, an accomplice for the killings and the humiliations of Muslims worldwide,” the young woman wrote.

Senouci also shared that the debate surrounding the Quebec government’s proposed Charter of Values, which sought to ban public sector employees from wearing religious symbols such as the hijab, solidified her feelings of being marginalized and being unwelcome in her own society.

And she wasn’t the only one.

According to a four-year study of foreign fighters who travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight with various jihadist groups since Syria’s slide into civil war following the Arab Spring in 2011, Senouci’s story is far from unique. The young woman experienced similar identity struggles, ideological aspirations, and susceptibility to outside influence as the 29 other foreign fighters interviewed for the study.

The study was conducted by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue and led by Canadians Amarnath Amarasingam, a senior research fellow at the institute, and Lorne Dawson, a professor at the University of Waterloo. The researchers compiled data collected from open-ended interviews with 30 men and women who travelled abroad to fight. They also conducted interviews with 43 of their parents, siblings and friends.

Of the 30 interview subjects featured in the study, 11 are Canadian. Twenty-seven of the foreign fighters were men and three were women. More than half (57 per cent) were born to Muslim families while the other 43 per cent were converts to Islam.

The researchers say their study focused on two key issues - the motivations of thousands of foreign fighters who leave home to fight in Syria and Iraq, as well as the difficulties their families and friends experience as a result - seeking some insight to prevent future radicalizations.

“They [the families] should be seen by the police and authorities as a resource to get through to these people because they’re still in communication with them,” Dawson told CTVNews.ca on Friday.

Radicalization in Quebec

According to the researchers, approximately 100 men and women have travelled to Syria and Iraq from Canada to fight with jihadist groups. Of the 11 Canadians included in the study, approximately one-third departed from Quebec.

Although the study stops short of providing a clear reason for this occurrence, the authors note that the young Quebec Muslims they interviewed expressed a “deep sense of uneasiness” about belonging in the province.

“They were born and go to school there, but as visible Muslims they do not feel included in the fabric of the province, one that is often openly hostile to their religious identity,” the report states.

Along with Senouci’s story of radicalization, the report shares the case studies of two other young men who left Quebec for Syria after they felt disillusioned with their society at home.

One of those men, Mohamed Rifaat, 20, became a religious leader among his friends in high school. A friend of his told the researchers that he was a “self-proclaimed imam” whose religious views became more conservative and radical in late 2012 and 2013. It was around this time that Pauline Marois led the Parti Quebecois, the party that introduced the Quebec Charter of Values, to victory in the provincial election.

“Every community led by a female will eventually become unsuccessful,” Rifaat wrote on his Facebook page at the time, according to his friend.

Rifaat’s Facebook posts eventually became more radicalized, even calling on the death of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and his supporters.

Dawson said, although it’s not the only contributing factor, the proposed Quebec Charter of Values bill and the debate it sparked made young Muslims question their place in society.

“It wasn’t prominent, but it was definitely a contributing factor. I think anyone would be lying if they didn’t admit that the social tensions in Quebec created by the Charter caused a certain amount of alienation to Muslim youth in Quebec that exceeded anything else being experienced in the rest of Canada,” he said.

Impact on families

Interestingly, the study found that nearly three-quarters (73 per cent) of foreign fighters continued to communicate with their family and friends back home. The report notes that, while many parents initially argued with their children about the decision to leave, they later opted to drop the arguments rather than lose contact altogether.

The researchers point out that this ongoing communication between families and foreign fighters could provide important opportunities to encourage them to return home or at least move to a safer area.

“If the young people start to become disillusioned, the parents will have to play a key role in cajoling them to leave and come back and surrender,” Dawson said.

Dawson stressed that the study highlights how difficult it is for parents and families to detect the process of radicalization. He said the majority of the subjects they interviewed were described as “good kids” who did well in school, weren’t involved in drugs or other criminal activities, and their families weren’t worried about them.

“It supports what we found and other people have found elsewhere that this stereotype of the troubled kid who then radicalizes, probably doesn’t hold true in most cases,” Dawson said.

The study identifies several common factors that contributed to the radicalization of their interview subjects.

- They experience an acute emerging adult identity struggle

- They have a moralistic problem-solving mindset

- They are conditioned by an inordinate quest for significance (to make a difference in the world)

- They believe in a religious ideology and participating in a fantasy (literally) of world change

- They are susceptible to the psychological impact of intense small group dynamics and influence of charismatic leaders

- They allow a fusion of their personal identity with a new group identity and cause

The report suggests that authorities need to provide more emotional and psychological support to the families of those foreign fighters who have left in order to learn more about these cases.

“The parents need more help,” Dawson said. “They need to be not seen as part of the problem, but seen as part of the victims. They need to be given more education and help going into these situations.”

The researchers said more public education for families on what they should look out for and what they should do if they suspect someone is becoming radicalized.

“Families are likely to be the first to detect something is happening to their child, yet the parents we interviewed, while being responsible and caring, had little sense of what they could do in the situation,” the report states. “A significant opportunity is being missed to detect radicalizing youth sooner.”