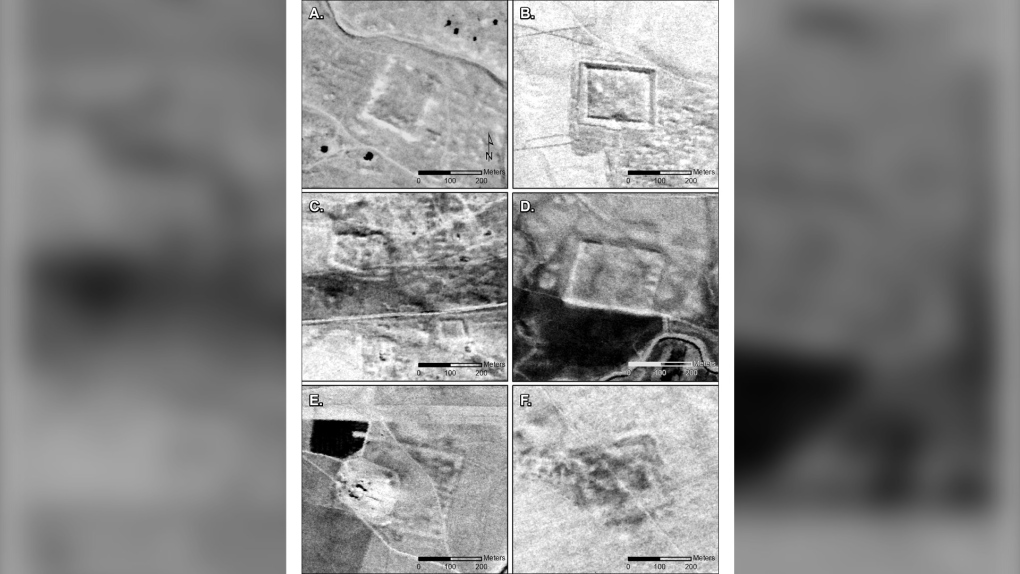

Researchers have discovered hundreds of Roman forts in modern-day Syria and Iraq using declassified spy satellite images taken during the Cold War.

A new study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Antiquity, says the work of archeologists has uncovered 396 previously undiscovered forts spread across the Syrian steppe.

While experts believed the Romans used these forts as a line of defence along their eastern border, the latest discovery points to another theory.

"The researchers hypothesize that the forts were actually constructed to support interregional trade, protecting caravans travelling between the eastern provinces and non-Roman territories and facilitating communication between east and west," the archeologists say in a news release.

The study is based on an initial survey of the area published in 1934 by Antoine Poidebard, a Jesuit missionary and explorer known for his work in aerial archeology.

His survey identified a line of 116 forts along the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire, the researchers say, which led to the belief that they were used to protect against Arab and Persian incursions.

"Since the 1930s, historians and archeologists have debated the strategic or political purpose of this system of fortifications," Jesse Casana, an archeologist from Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and lead author of the study, said.

"But few scholars have questioned Poidebard's basic observation that there was a line of forts defining the eastern Roman frontier."

Using Poidebard's forts as a reference, as well as declassified images from the U.S. government's CORONA and HEXAGON spy satellites from the 1960s and '70s, Casana and investigators from Dartmouth were able to find the additional forts.

They say the wide distribution of the forts, from east to west, does not support the argument that they formed a north-south border wall, as Poidebard and others had believed.

Instead, the researchers say this suggests the eastern border was not as rigidly defined and "likely not a place of constant violent conflict."

Rather, they suspect the Romans used these frontiers as places of cultural exchange.

In their study, the archeologists say Poidebard's initial discovery could be the result of "discovery bias," considering he flew over areas where he believed the forts would most likely be located.

"None of this is intended to diminish Poidebard's achievements as a pioneer of aerial archaeological survey, nor the important discoveries he made. His research was conducted before the first formal archaeological surveys in the Near East, and long before there had been any theoretical or methodological consideration of survey design within archaeology," the study says.

"Nonetheless, our results offer a completely new perspective on the distribution of forts across the region and reopen discussions regarding their military, political and economic functions."

The researchers say many of the likely Roman forts they documented have been destroyed by recent urban or agricultural development, with "countless others … under extreme threat," making large-scale recording of archeological landscapes "especially vital to heritage preservation."

The further declassification of satellite imagery, they add, could help with future discoveries.

"As recent scholarship reimagines Roman frontiers as sites of cultural exchange rather than barriers, we can similarly view the forts of the Syrian steppe as enabling safe and secure transit across the landscape, offering water to camels and livestock, and providing a place for weary travellers to eat, drink and sleep, thereby playing a critical role in bringing east and west together," the study says.