Warning: This story deals with themes that some might find upsetting

The end of January was an anniversary of sorts for Kimberly Polman. Time counted in despair, sickness, fear, suicide attempts, searing desert heat in the summer, howling wind and swirling dust in the winter. Hepatitis, broken teeth and tent fires.

It is three years since she was arrested by Kurdish fighters in northeastern Syria and sent to a detention camp for her alleged association with ISIS.

Polman insists she was neither an activist nor supporter. That she was lured into the violent ISIS underworld by a man who promised marriage, and an opportunity to help the suffering people of Syria.

She went -- stupidly, she admits -- and is now paying for it with a loss of her freedom. And the real prospect of dying there.

“Mentally, I’ve gone downhill, especially the last year,” she told me. “I attempted to take my life several times and I can see serious signs of depression in some of the other Canadian women as well.”

A dozen or so Canadian women and their children have been held in the Kurdish camps since 2019, along with many other foreign families. Kept under armed guard, housed in flimsy tents, in conditions often described with a single word—dire. Kimberly Polman, age 49, is the oldest Canadian.

“Almost everyone’s got breaking teeth,” she told me. “And they’re not just breaking, like cracking. It’s almost like they’re tearing off because they’re soft.”

A team of human rights experts from the United Nations recently became involved directly in Polman’s case and warned Canada that her life is in jeopardy.

“The dire conditions in which she is detained are life-threatening,” said the UN report, “and may amount to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Under Canadian government guidelines, that have not been publicized and are very restrictive, she is the only Canadian detainee who meets the criteria for possible repatriation. The others, it seems, have little hope of leaving.

In its description of Polman’s condition, the UN document says she has lost more than half her body weight; has been detained without charge, without trial and without access to a lawyer.

“Her family is aware that Ms. Polman has been suicidal.”

Peter Galbraith, a former U.S. diplomat, recently offered to escort Polman out of the camp, but Canada withheld its co-operation. Galbraith, who has been involved in rescuing other Canadians, left empty-handed.

He had also offered to rescue a 9-year-old Canadian boy who is seriously asthmatic.

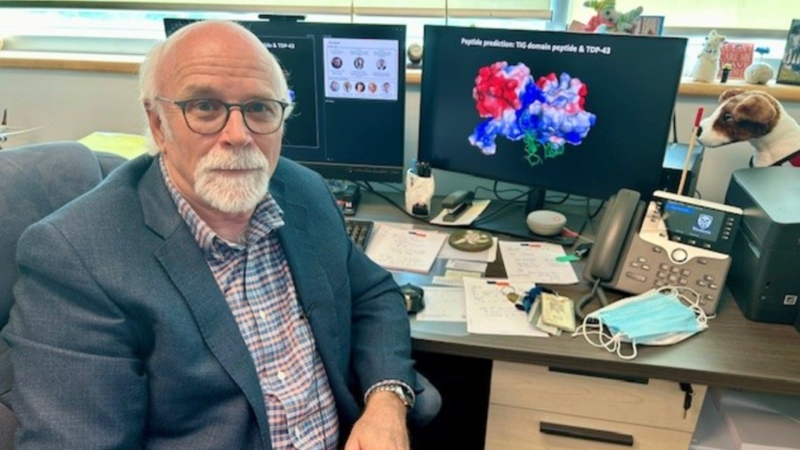

Dr. Alexandra Bain, the founder and director of a family support group, pleaded with Global Affairs Canada to approve Polman’s release. Without urgent action, she warned, the next step might involve arranging for the return of her body.

“All Canada needed to do was send an email to the Kurdish authorities, and a very sick woman could have been on her way to Canada. They wouldn’t even do that.”

Global Affairs did not respond directly to questions about the failed rescue, though government officials have been confirmed they are aware some detainees may be struggling with deteriorating physical and mental health.

As Ambassador Galbraith was waiting for an answer from Canada, members of Polman’s family in British Columbia were preparing to fly to Iraq and bring her home. It was a futile effort. There was a plan, but no rescue.

As February settles in, the Canadian women and children are now entering their fourth year of detention. Everyone’s sick, Polman told me, and tent fires are common. They’ve been supplied with open flame heaters.

“In one month we had 17 tents burn down.”

When I first met her, she was dressed in full hijab, but now wears western clothes, as do most of the Canadian women. They stand out from others who continue to support ISIS.

“You just have to wait for your government to rescue you,” said Polman in one of her voice messages, interrupted by a deep-sounding chest cough.

“To give you your rights as a human being.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, here are some resources that are available.

- Canada Suicide Prevention Helpline (1-833-456-4566)

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (1 800 463-2338)

- Crisis Services Canada (1-833-456-4566 or text 45645)

- Kids Help Phone (1-800-668-6868)

- If you need immediate assistance call 911 or go to the nearest hospital.