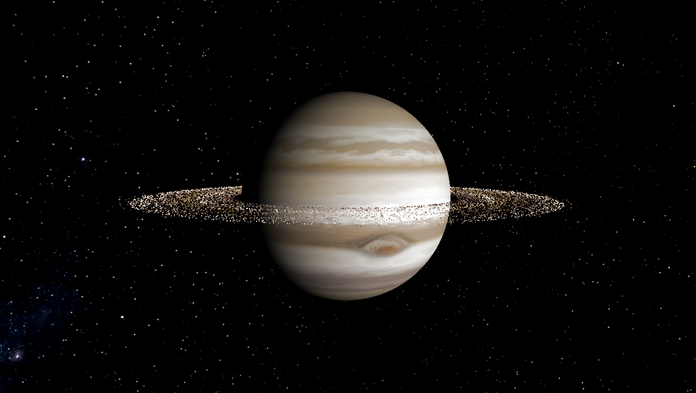

The biggest planets in our solar system have a ring orbiting around them, with Saturn’s stunning, massive disc being the most well-known example.

But if rings are common around larger planets, why doesn’t Jupiter have an impressive ring to rival Saturn’s?

The answer, according to a new study delving into this question, is that Jupiter’s moons would tear apart a large ring system before it even developed.

“It’s long bothered me why Jupiter doesn’t have even more amazing rings that would put Saturn’s to shame,” Stephen Kane, an astrophysicist with the University of California, Riverside, said in a press release. “If Jupiter did have them, they’d appear even brighter to us, because the planet is so much closer than Saturn.”

Planetary rings are made up of a swirling collection of pieces of rock, ice and dust. They can feed the formation of moons, or moons can feed more material into the ring systems, with these dynamics depending on a careful balance of orbital configurations.

The four largest planets in our solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus — actually do all have rings, but Jupiter and Neptune’s are so faint that they weren’t discovered for years. Jupiter’s thin ring of dust was only spotted in 1979.

“We didn’t know these ephemeral rings existed until the Voyager spacecraft went past because we couldn’t see them,” Kane said.

Invisible in almost all photos we have of Jupiter, its rings are mostly just a suggestion, showing up as a faint line only when viewed from behind Jupiter and lit by the Sun. But considering Jupiter’s majestic size, why not bigger rings?

Kane, along with graduate student Zhexing Lin, sought to answer that question through computer modelling that looked at Jupiter’s lifespan, its orbit and the orbit of its moons.

What they found, described in a paper available online ahead of publication in the Planetary Science Journal, was that Jupiter’s largest moons were responsible for disrupting the formation of any significant rings.

Jupiter actually has 79 moons, while Saturn has 82. But four of Jupiter’s moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — make up 99.997 per cent of all of the mass orbiting Jupiter.

They are so massive that the astronomer Galileo Galilei was able to spot them in the early 1600s. They were the first moons to be identified outside of our own.

While some of Saturn’s smaller moons exist within its ring, providing it with new material and also “shepherding” it around the planet, Jupiter’s four Galilean moons discourage ring formation through their sheer mass as well as the distances they are to each other and to Jupiter.

“We found that the Galilean moons of Jupiter, one of which is the largest moon in our solar system, would very quickly destroy any large rings that might form,” Kane said.

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, which is similar in size to Jupiter’s Galilean moons, orbits closer to Saturn than the ring does, and only affects it slightly.

“Titan is relatively far from the main ring structure, but its presence does result in a ringlet within the inner C ring through the effect of orbital resonance,” the study noted.

Meanwhile, the moon Io orbits Jupiter at the same distance from Jupiter as Saturn’s ring from Saturn.

The orbital configuration of Io, Europa and Ganymede indicate that Jupiter’s moons may have closed in on the planet either during their formation or shortly afterward, a time period in which their gravity may have halted the formation of a massive ring in its tracks, the study suggests.

In the study, researchers ran a computer simulation where they introduced particles that could have formed a ring to Jupiter’s orbit, only to watch around half of them be thrown out or absorbed by the moons over a period of 10 million years — a short time span when it comes to space.

The study stated that this shows the “Galilean moons carve a substantial area of instability into the region around Jupiter that may only allow relatively short-lived ring systems to co-exist with the orbital architectures.”

They added in their conclusions that this could mean that even the current ring around Jupiter may be relatively young, and that it is unlikely that Jupiter ever had massive rings, even in the past.

As a result, it is unlikely that Jupiter had large rings at any point in its past.

“Massive planets form massive moons, which prevents them from having substantial rings,” Kane said.

So why does it matter? Scientists believe that learning more about the formation of rings and moons close to home could help us understand more about planet formation far beyond our own solar system.

A planet’s rings can reveal its past, such as providing evidence of previous collision events.

“For us astronomers, they are the blood spatter on the walls of a crime scene,” Kane said. “When we look at the rings of giant planets, it’s evidence something catastrophic happened to put that material there.”

For instance, one theory regarding Saturn’s rings themselves is that a massive moon was torn apart by tidal forces while plummeting towards the planet, with that debris joining other space rocks and ice to spiral endlessly around the planet.

Kane hopes to study the formation of Uranus’ rings next, which are the second brightest in our solar system after Saturn’s, and are actually more substantial despite being smaller.