A chemistry student in Newfoundland may have discovered an alternative to plastic using fish guts.

In a St. John’s lab, Memorial University master’s student Courtney Laprise works with oils extracted from waste products such as fish heads and intestines.

Yes, it smells, she told CTV’s Your Morning on Friday -- but not once she’s done with it. The end product is what matters anyway, she said. Laprise hopes her findings could one day become a pivotal alternative to the plastics that pollute the environment.

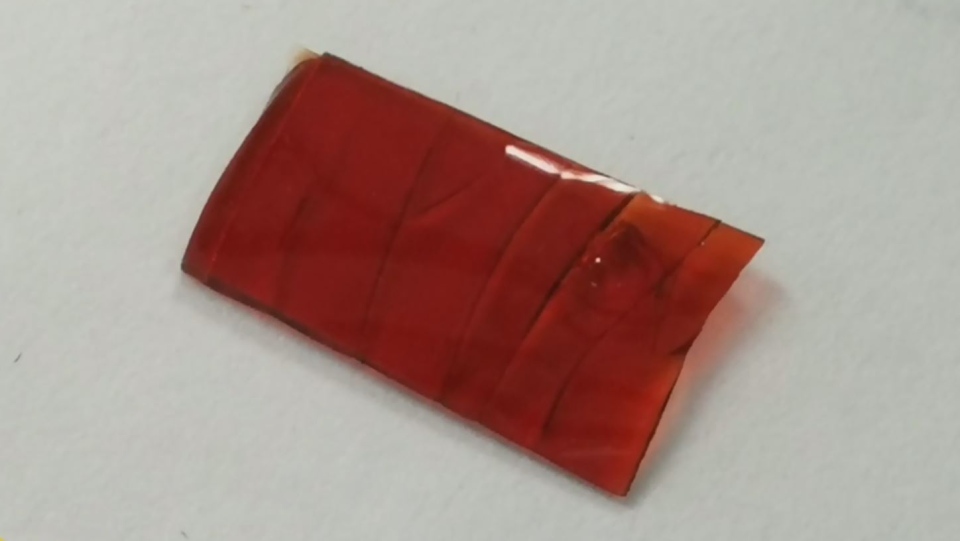

Though the exact chemical recipe is a proprietary secret, the process involves performing several reactions with the fish oil and transferring it to a petri dish. Then the dish is put into an oven to be cured. After some time the substance becomes a “nice plastic,” said Laprise.

“It can be used as different plastics. Maybe a film or adhesive. With some other modifications there are some potential routes it could be used for,” she said Friday.

It took several months of failed attempts producing only liquid substances before she eventually produced her first solid product.

A number of companies have already expressed interest in Laprise’s research. She’s particularly excited that the fish-produced alternative to plastic could mean big business for small fishing communities from her native Newfoundland.

Other sustainable efforts using fish waste are popping up around the world, including in the leather fashion industry. An Icelandic company called Atlantic Leather produces thousands of skins of fish leather every month from salmon, perch, cod and wolffish sourced from fishing fleets in Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands. They use geothermal energy for eco-friendly production, according to the BBC, unlike other forms of leather, which are associated with methane emissions. Like Laprise’s plastic alternatives, there are hopes that fish leather could boost fishing communities.

There’s still some research to be done before Laprise’s plastic becomes a viable product in the market. She’s currently studying how long it takes for the fish oil-produced product to biodegrade. Traditional plastic takes hundreds of years to decompose in the natural environment. There are a number of important tests being done now.

“Whether it degrades into toxic materials,” she said. “If it just gets thrown in the landfill, will it degrade?”

It’s important to Laprise that she use clean and “green” methods during all her research. “I’m trying to use things that are good for the environment, safe for human health,” she told Your Morning. To use less energy, for example, she uses lower temperatures in the curing process.

“If we can replace plastics that are polluting the environment, in my opinion, it is still better,” she said.