Scientists may have pinpointed a massive, oddly shaped volcano taller than Mount Everest on the surface of Mars — and it has been hiding in plain sight for decades, according to new research.

The possible identification of a previously unknown Martian volcano has made waves across the planetary sciences community since Mars Institute Chairman Dr. Pascal Lee, lead author of an abstract about the formation, presented the findings on March 13 at the 55th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

The research has drummed up excitement — and attracted some skeptics.

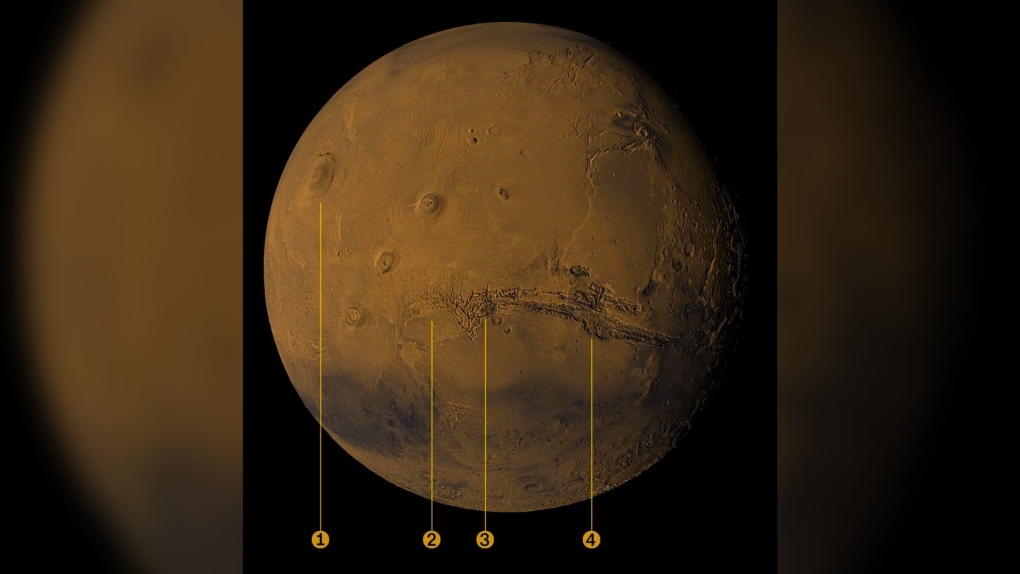

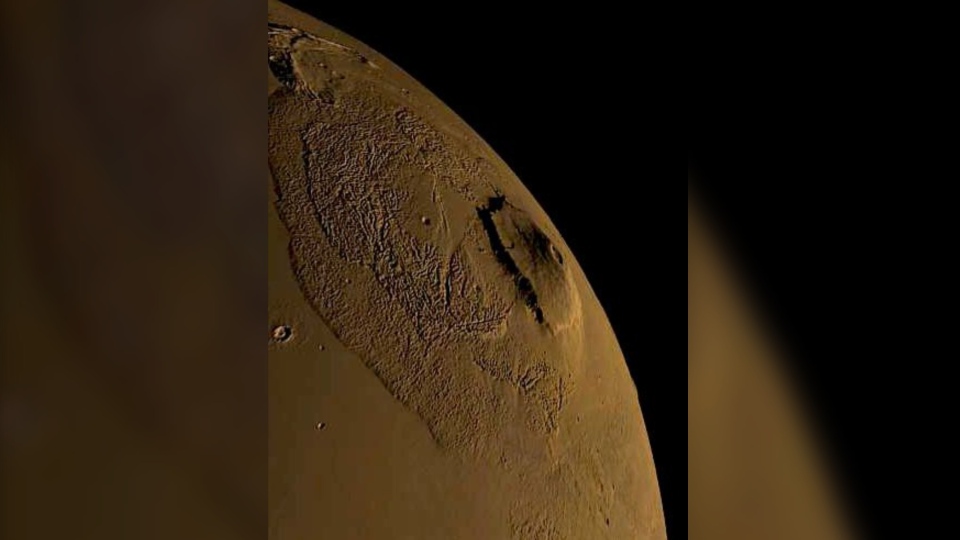

Lee said he and Sourabh Shubham, a doctoral student of geology at the University of Maryland, College Park, have identified a volcano within Mars’ Noctis Labyrinthus region — a gnarled patch of terrain near the equator with a web of canyons. The volcano in the “Labyrinth of Night” may have eluded scientists despite years of satellite observation because it does not tower over its surrounding landscape, Lee said.

"It’s also deeply eroded, eaten up and collapsed by erosion to the point that unless you’re really looking for a volcano, you would be really hard-pressed to spot it very quickly," he told CNN.

If the team is correct, the revelation could have broad implications for scientists’ understanding of Martian geology. And, Lee said, he hopes the discovery could help lure future exploratory missions to the area to search for water ice or even signs of life.

The smoking gun

Initially, the research team’s efforts led to a study presented in March 2023 that suggested the Noctis Labyrinthus region may be home to a massive glacier covered in salt deposits.

Since then, Lee and Shubham have pored through data collected by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, trying to determine whether water might still be frozen beneath the salt.

The hunt for water ice is key — it’s a resource that could be used to sustain human exploration on Mars or even converted into rocket fuel. While scouring the landscape, however, Lee said he was struck by “this little lava flow next to the glacier.”

The lava hadn’t yet been fully oxidized, a process that would turn it the same muddy orange hue as the surrounding surface, Lee said.

That indicated the lava might be relatively fresh — the first hint that an undetected volcano might be lurking nearby.

“We started looking at the landscape carefully,” Lee said. “And sure enough, when we examined the high points of this region, we noticed that they formed an arc.”

That arc is reminiscent of a shield volcano, Lee added, a type of volcano that also exists on Earth. Shield volcanoes are characterized by their broad, gently sloping sides — appearing wider than they are tall.

That finding led Lee and Shubham to gather more evidence, eventually determining that a 29,600-foot (9,022-metre) peak was actually the tip of a Martian volcano.

That’s a few hundred feet taller than Mount Everest, which rises 29,029 feet (8,848 metres) above sea level.

Mapping Mars

Scientists have already cataloged and named more than a dozen volcanoes on Mars, including Olympus Mons, the tallest known volcano in our solar system.

Lee said he and Shubham are working to spell out the findings in a peer-reviewed paper, a more detailed work that could lend more credence to the idea across the scientific community.

But the hypothesis of the volcano’s existence is already attracting attention.

“It’s a big thing,” said Dr. Adrien Broquet, a Humboldt Research Fellow at the German Aerospace Center who has studied Martian volcanoes. “It’s as tall as the tallest mountain we have on the Earth. So, it’s not a small feature on Mars for which we’ve had a question mark. And we have plenty of question marks (about the surface of Mars.)”

A search for life in the Labyrinth of Night

The journey to identifying this volcano — which the team has provisionally named “Noctis volcano” — began in 2015, Lee said, when NASA asked the planetary science community to propose intriguing locations on Mars where the US space agency might land future human exploration missions.

Lee proposed a site just east of Noctis Labyrinthus, which was dubbed “Noctis landing.”

The location could be an ideal place to search for alien life on Mars, said Lee, who is also a planetary scientist at the SETI Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to searching for evidence of extraterrestrial life.

“Of course, we’re not looking for a little green man with antennae,” Lee said. “But we’re looking for microbes that would not fit into the tree of life on Earth.”

Noctis Labyrinthus could be ideally situated for this hunt, according to Lee.

“If you want to look for ancient life, you drive east (from Noctis Labyrinthus) into the canyons,” Lee said, referring to Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in our solar system.

There, explorers could “sift through the rock layers” to scour for fossils, he said.

Or, Lee suggested, a mission could venture west to a volcanic region called the Tharsis plateau, where warm caves may harbor living microbes.

With such tantalizing potential, Lee has committed to studying Noctis Labyrinthus to build a case for sending exploratory missions there.

A volcano, a glacier and the history of Mars

The existence of a volcano in Noctis Labyrinthus could also help explain the creation of this bizarre landscape.

Scientists suspect magma bubbling up from Mars’ interior formed the labyrinthian valleys, but the details are up for debate.

One theory is that when the magma pushed up on the Martian crust, it cracked and splintered, leaving behind a maze of branching canyons.

Lee favours an alternative theory: This model suggests that the Martian crust in Noctis Labyrinthus is full of ice. And when magma seeped in, it melted or vaporized ice and rock beneath the surface, causing swaths of the terrain to cave in.

The existence of a volcano in the region, Lee said, might offer more support for the latter theory.

The science of certainty

Three scientists who were not involved in the research told CNN that they would not be surprised if a volcano were hidden near Noctis Labyrinthus.

Volcanoes of all shapes and sizes riddle the surface of the broader region, including the Tharsis plateau to the west of Noctis Labyrinthus.

However, Dr. Ernst Hauber, a staff scientist at the German Aerospace Center’s Institute of Planetary Research, is one geologist in the community who would like to see a peer-reviewed paper before he accepts Lee and Shubham’s version of events.

“They are very vague about chronology, about the timing of events,” Hauber told CNN, referring to the brief abstract Lee and Shubham published.

Among Hauber’s questions: If the volcano could still be active, as Lee suggests, why hasn’t it poured lava into the surrounding canyons? Why aren’t there more visible signs of lava near the peak? Could this actually be an impact crater Lee is looking at?

“I’m a bit skeptical for several reasons,” Hauber said.

Broquet of the German Aerospace Center and Dr. David Horvath — a research scientist at the nonprofit Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona — both said in separate interviews they would like to see additional data supporting the ideas Lee and Shubham presented.

But Broquet and Horvath said they find the abstract intriguing.

“This does look like a really good candidate (for a volcano),” Horvath said.

Lee said he is welcoming input from other scientists, anxious for additional evidence to support his research. But he also expresses confidence.

“In this case, my sense is that there’s really no room for plausible alternate hypotheses,” Lee said, adding that he’s 85% to 90% certain he has located a new Martian volcano.

“But extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” Lee added, quoting the late astronomer Carl Sagan, for whom he once worked as a teaching assistant.