Canadians value our public health system and want to preserve free, universal care that will always be available, no matter how wealthy you are and no matter where you live in the country.

It’s good for patients needing care and it’s also good economically as it enhances interprovincial mobility. It also reduces the burden that falls on individuals and employers in countries, like the U.S., where it’s everyone for themselves.

It’s a defining element of our national identity and reflects Canada’s history and our values.

Our health-care system has been stretched to the limit by the pandemic. The provinces have, justifiably, been calling upon Ottawa to pay a bigger share. The original deal, two generations ago, was a 50-50 split of costs between the feds and the provinces. There’s some debate around the exact figure, but the current share is closer to 70-30, with the lion’s share coming from the provinces.

One of the first things that has to be developed is a common definition of what’s included. You can’t honestly claim to know who’s contributing what percentage if you don’t have agreement on that.

FINDING THE BEST PATH FORWARD

It was a source of both hope and concern to see the provinces get together this week to discuss the issue in New Brunswick. Hope, because the provinces arrived with a far more constructive tone than the “send the cheque” approach they’ve taken in the recent past. Concern, because some of the “solutions” could undermine the very foundations of our health-care system.

Finding the best path forward is going to require good faith on all sides. It’s just too easy for the feds, and it produces zero results, when the provinces can be sloughed off as a bunch of perpetual whiners. It’s too easy for the provinces, and it produces zero results, when they just point fingers at Ottawa and provide no concrete solutions.

The situation is urgent and the last thing we need is another lengthy study with a massive report that will gather dust beside the other massive reports generated every decade or so. We know the problems: insufficient funding; lack of accountability and disagreement as to how to measure outcomes.

Canada's large cities have also been showing that they have a major role to play in health care. During the pandemic, cities such as Toronto and Montreal had public health services with closer connection to communities that proved essential. They have to be at the table as well.

There are solutions. There are just no easy solutions.

It’s complicated. The complication begins with the simple constitutional fact that health care in Canada is first and foremost provincial jurisdiction. Nothing riles up a provincial healthcare official more than the thought that some bureaucrat in Ottawa wants to evaluate their performance. There are ways to fix that, the most important being the agreed transparent publication of objective information. Don’t want someone else to grade your work? Fine, agree to provide all the information needed to evaluate, publish it and let the voting public assess.

IS PRIVATE HEALTH CARE ON THE WAY IN ONTARIO?

The feds don’t run the hospitals in the country, the provinces do. Or, to put it another way, when the only health care you do provide is to the Armed Forces, First Nations and in federal penitentiaries, you should be very modest in claiming to evaluate anyone else’s performance. This type of approach could help avoid that needless quarrel.

When Doug Ford drops a prepared line like "The status quo is not working, folks," at the premiers’ press conference, it’s also easy to know where he’s headed. He’s already been providing hints with his post-election decisions: fewer services for the most vulnerable like poor seniors and, more ominously, more private health care.

The siren song of the “savings” to be made by tasking the private sector to provide more health-care services is an illusion.

It’s bit like the private schools that can boast better outcomes because they get to choose which kids they admit. The public system, of course, is there for everyone.

In health care, our public system is also there for everyone. Hospitals don’t pick and choose and that’s a good thing. A homeless person or someone with serious mental health issues is still going to be admitted and treated the same way as anyone else.

THE MOVE TO PRIVATIZATION

In the private sector, there will be far less access for people at the bottom rung of the ladder. Oh, sure, the private hospitals and clinics will come up with figures showing that they can perform cataract surgery or do a knee or hip replacement cheaper than the public system. The problem is, they’ll be making big profits by skimming off the easiest patients. The comparison isn’t fair but it’s a prejudice that’s increasingly shared. This move to privatization is the Trojan horse in this debate and that’s why establishing and maintaining the founding principles of our system (and enforcing the rules of the Canada Health Act) is so essential.

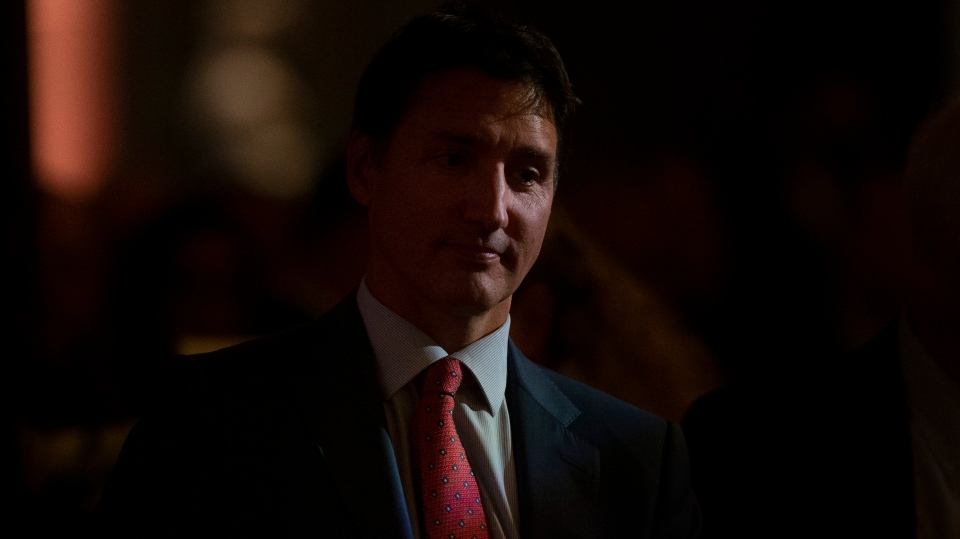

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has had an easy time of it since he and NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh hit their three-year snooze button. He’s been going through the motions. Bureaucrats have been taking up the slack, pushing their pet projects.

The most recent example was technocrats contriving to bring fundamental change to official language rules in the federal government with absolutely no constitutional, Parliamentary or political authority. The same types of bureaucrats that overrode Canada’s policy towards Russia and decided to attend a garden party at the Russian Embassy, celebrating the regime at war with Ukraine. That sort of thing!

Trudeau has a subject that could be a legacy project for himself and his government. Other than legalizing pot, his balance sheet is quite thin when it comes to results. Unfortunately, he seems to lack the drive, vision and will to actually do something to improve health care.

As New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs said: “Urgent action is needed if the federal government wants to ensure the sustainability of health care and services across Canada.” It must rapidly be made a national project that rallies the best minds from across the country.

This is the right moment to act. All the elements are coming together: a strong public desire to protect and improve our system. Provinces that show a more mature willingness to sit down and find solutions; and a health system in dire need of constructive new ideas. What’s missing is any structured, serious response from the feds.

Trudeau has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to address this great national priority and accomplish something fundamental for the future of health care. The problem is, so far, he just doesn’t seem interested.

Tom Mulcair was the leader of the federal New Democratic Party of Canada between 2012 and 2017