The federal government is granting British Columbia’s request to recriminalize hard drugs in public spaces, nearly two weeks after the province asked to end its pilot project early over concerns of public drug use.

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Ya’ara Saks made the announcement Tuesday on Parliament Hill.

“We have said yes, and it is effective immediately,” Saks told reporters.

B.C. is little more than a year into a three-year pilot project to decriminalize the possession of a small amount of certain illicit drugs, including heroin and cocaine.

But citing safety concerns from public consumption of those drugs, the B.C. government asked the federal government on April 26 to make illicit drug use illegal in all public spaces, including in hospitals, on transit and in parks.

Saks said the issue is a “health crisis, not a criminal one,” but that “communities need to be safe.”

According to a statement from Saks’ office, exemptions in the Criminal Code for possession of small amounts of illicit drugs for personal use will still apply in private residences, certain health-care clinics, places where people are lawfully sheltering, and overdose prevention and drug checking sites.

B.C. Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside said at a press conference Tuesday those exemptions will give people using at home the ability to "call for help without fear of being arrested."

"The vast majority of people who die from toxic drug poisoning are dying at home alone," she said.

"The intention of decriminalization was never about providing space for unfettered public drug use. That was not the intention. The intention was to ensure that people felt that people should not be afraid to reach out for help wherever they were using."

When asked by reporters why the federal government took more than a week and a half to make the decision to abandon the pilot program, Saks said it is “the illegal toxic drug supply,” and not decriminalization, that is causing overdose deaths.

“Moving forward to any kind of pilot like the one in B.C., we know that we have to have a balance, public safety and public health,” she said. “That means there needs to be sufficient health services in place, scaled out to meet people where they're at, and also law enforcement to have the tools that they need to ensure that public safety is a priority.”

Saks added that decriminalization is one of the pillars of the Liberals’ policy approach to tackling the opioid crisis, and that while the federal government recognized the “urgency” of B.C.’s request, it didn’t want to make a decision based on “knee-jerk reactions.”

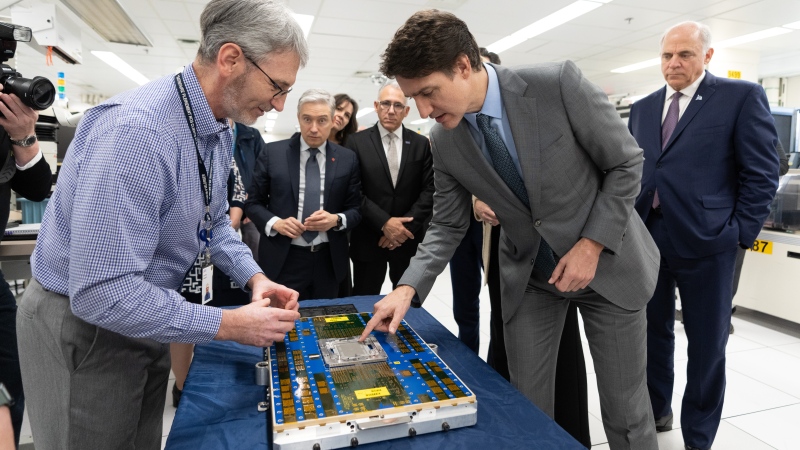

The issue sparked tense debate in the House of Commons last week, when Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre pressed the Liberals to accept B.C.’s request. One fierce exchange saw Poilievre ejected after calling Prime Minister Justin Trudeau "wacko" for his drug decriminalization policy.

Poilievre and Trudeau were back on the topic Tuesday following Saks’ press conference, with the Conservative leader pressing the prime minister over whether he will “try to impose the same radical and extremist policy” in other jurisdictions, paving the way for people to legally

“smoke crack in children’s soccer fields.”

“Obviously no one in this House does,” Trudeau responded.

“That is why we agreed with the British Columbia government to modify their pilot project to better suit their concerns,” he added, before accusing Poilievre of politicizing the issue.

With files from CTVNews.ca’s Senior Digital Parliamentary Reporter Rachel Aiello and CTV News Vancouver’s Robert Buffam