Economic uncertainty, big-ticket promises and few details about where the money's going to come from has the Conservatives, the Liberals and the NDP all flirting -- for the moment -- with the prospect of a budget deficit during their first year in power, a Canadian Press analysis of campaign commitments suggests.

At this early stage of the federal campaign for the Oct. 19 vote, all three parties combined have made billions of dollars worth of promises so far, but have been far less forthcoming about how they intend to pay for all those investments, benefits and tax breaks.

Moreover, renewed economic worries have raised questions about whether the parties will be able to afford all of their promises, and which of the three main parties could actually balance the books -- or even if they should.

"I don't think there is a really strong argument, or any real argument, to be made that the budget must be in balanced no matter what the state of the economy is," said Allan Maslove, an expert on government budgeting at Carleton University in Ottawa.

"Spending and taxation are instruments of government policy that should be used to regulate the economy and promote growth and sometimes that means running a deficit and sometimes that might mean running a surplus, but that's a function of where the economy is going at any point in time."

To determine how close the parties were to running a deficit based on their promises to date, The Canadian Press tabulated the cost of those promises, as well as key planks that were unveiled prior to the official start of the campaign, such as the NDP's proposed national child care plan.

In some cases, the parties have put specific timelines on how much their promises will cost in each of the next four fiscal years, while in others they have made broad promises for multi-year spending without saying how much of the money would be spent up front and how much would be spent in later years. In those instances, The Canadian Press evenly divided the full cost of multi-year promises.

Promises without cost estimates were not included.

Each of the parties were given a spreadsheet containing their spending promises and asked to provide additional details where possible.

What's clear is this: the space in the budget in the next two fiscal years has contracted, along with the economy.

Revised estimates from the parliamentary budget office last month pegged the federal surplus at $600 million next fiscal year, and $2.2 billion the year after -- a result of lower interest rates and plunging oil prices, among other issues, that affect the government's bottom line.

Based on those projections, the analysis suggests the Conservatives would have a surplus of $727 million next fiscal year, an amount that includes using part of a contingency fund set aside for emergencies. Conservative Leader Stephen Harper has vowed to balance the books, even though the PBO projections have cast doubt on a balanced budget this year.

The NDP are tracking to have a surplus of $1.19 billion in their first year, based on much of their spending promises being ramped up over a four-year period, or -- in the case of the child care program -- an eight-year climb to $5 billion in annual spending. NDP Leader Tom Mulcair has been adamant his party wouldn't run a deficit in their first fiscal year if elected this fall.

The party has yet to unveil some spending details, as well as its plan to raise corporate taxes. A one per cent increase in the federal corporate tax rate could raise upwards of $1.3 billion in revenue per year, based on various estimates. But eliminating income-splitting and the doubling of limits on tax-free savings accounts should save about $2 billion and $160 million, respectively, next fiscal year.

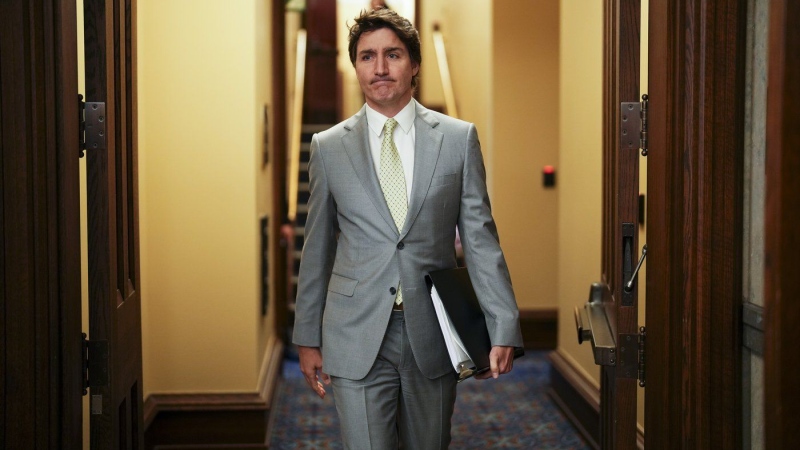

The Liberals appear to be $2.38 billion in the red next year, based on their promises in the absence of any new revenue streams or cuts in spending. Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau has indicated his party may run a deficit and hinted it could take years to return to balance.

In the 2017-2018 fiscal year, all three parties are tracking to run a surplus: the Conservatives at $2.72 billion, the NDP at $3.56 billion, and the Liberals at $1.39 billion.

All of the estimates rely on the PBO's projections holding steady with no additional economic shocks.

All the promises combined have led to heated campaign rhetoric about which party would raise taxes, although the subject doesn't have to be taboo, said Aaron Wudrick, federal director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation.

The issue, Wudrick said, is whether Canadians are getting good value for their money.

"If they truly felt that they would get much better value with a tax hike, most of them would probably be okay with a tax hike," he said.

"The fact that they aren't suggests that they are not convinced that the tax hike will give them good value for their money."

Wudrick said his group would rather see parties vow to cut subsidies to businesses that cost the government about $1 billion per year. "To us it's a no-brainer, these are successful businesses. They do well in the market. Why the government feels the need to give them additional money out of the public purse just makes no sense."