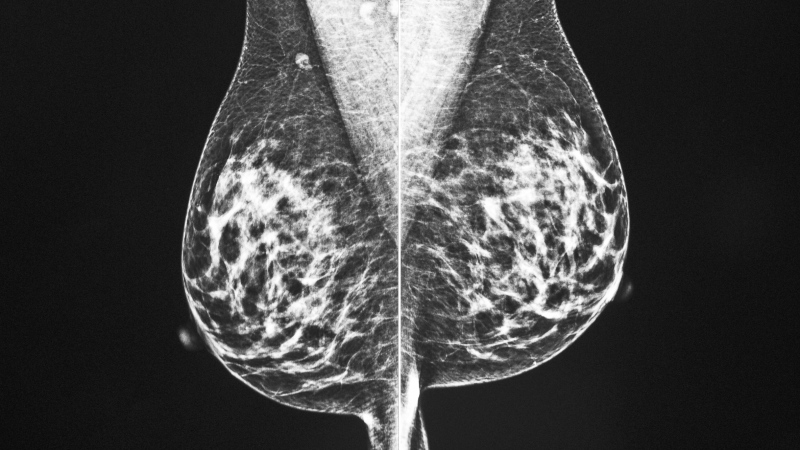

For years, doctors and researchers studying organ donations have noted a trend consistent around the world: women are more likely to donate a kidney than to receive one.

The reasons behind that gender imbalance are not always easy to pinpoint, but experts say kidney donations from women are often tied to economic and cultural factors.

To mark World Kidney Day on Thursday, which coincides with International Women’s Day, the International Society of Nephrology and the International Federation of Kidney Foundations is highlighting the unique challenges women face when it comes to kidney disease and transplants.

According to data provided by World Kidney Day organizers, 62 per cent of kidney transplant recipients in Canada are male, while only 38 per cent of recipients are female.

Women make up 58 per cent of living kidney donors, while 42 per cent are male. In the U.S., that gap is even wider, where living kidney donors are 63 per cent female and 37 per cent male.

Several studies have also noted gender imbalances among living kidney donors in some European countries.

“Women are much more likely to be living donors for kidney transplant than men and that is a statistic that we have known for quite a while,” said Dr. Adeera Levin, professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia and the executive director of the BC Provincial Renal Agency.

“This seems to hold no matter where we look … so it is a worldwide phenomenon,” she told CTV News.

Dr. Levin said there a number of reasons why women might be more likely to donate a kidney than men.

She said that in some cultures, women are expected to help family members in need and that includes donating a kidney to their ailing husbands or children. In societies where men are typically the breadwinners and women don’t have full-time jobs, women are seen as being in a better position to give a kidney to their husband.

Dr. Levin said women are also often in better health than men as they age, which makes them better candidates for organ donation.

Some researchers have also suggested that women might be “more vulnerable to subtle pressures” to donate a kidney to a family member.

Dr. Kathryn Tinckam, a transplant nephrologist at the University Health Network in Toronto and the chair of the kidney transplant advisory committee for Canadian Blood Services, said some people may interpret the data on kidney donation as an indication that women are more altruistic or caring. But she said that’s not necessarily true.

“I think we have to be very careful in avoiding those stereotypes and recognize that we still have a lot of living donors who come forward that are men,” Dr. Tinckam told CTV News.

She said there are often biological reasons for the gender disparity among living kidney donors.

Men are more likely to be kidney recipients because they are more likely to be on dialysis and require a transplant, she said. And conditions that can exclude someone from being a living kidney donor, such as hypertension and cardiovascular disease, can occur more often in men.

One study published in the Lancet a decade ago suggested that transplantation of male donor kidneys into female recipients was more prone to failure.

Dr. Tinckam said that women face additional barriers while waiting to be matched with a kidney donor.

“Because of pregnancy, women have a greater chance of having their immune system make antibodies that could make it more difficult to match a donor,” she said.

Whatever the reasons, the gender imbalance means that ailing women often wait longer for a kidney transplant. Georgina Kinney, a 62-year-old patient in Vancouver, is among them.

She currently undergoes dialysis four times a day and has been waiting for a kidney transplant since 2004.

“It nearly caused my death. Without dialysis, I wouldn’t be here,” she told CTV News.

No donor match has been found for Kinney yet.

“I keep hoping every day that somebody comes up,” she said. “My biggest fear is not being able to get the transplant and dying. I don’t think I’m that old – I’d like to live a little longer and I’d like to see my grandchildren grow up.”

Chronic kidney disease

World Kidney Day organizers are also highlighting the fact that women are more likely to suffer from advanced stages of chronic kidney disease or CKD. That’s because women with serious CKD tend to live longer than men and it takes them longer to reach the critical stage of disease where a transplant is required.

An estimated 12 per cent of the general population worldwide has chronic kidney disease. While there are more men than women on dialysis for reasons that “are not fully understood,” data from different countries, including Canada, U.S. and the U.K. show that higher proportions of women live with advanced CKD.

Researchers also note that women with CKD who want to have a baby face increased health risks, including preterm delivery and preeclampsia (high blood pressure complications during pregnancy).

Women with CKD often require daily dialysis during pregnancy, but that’s not always possible for those living in developing countries, researchers say.

With a report from CTV’s medical affairs specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip