Hospitals in Toronto are experiencing a surge in premature babies, leaving many hospitals to scramble to find beds for these sick infants.

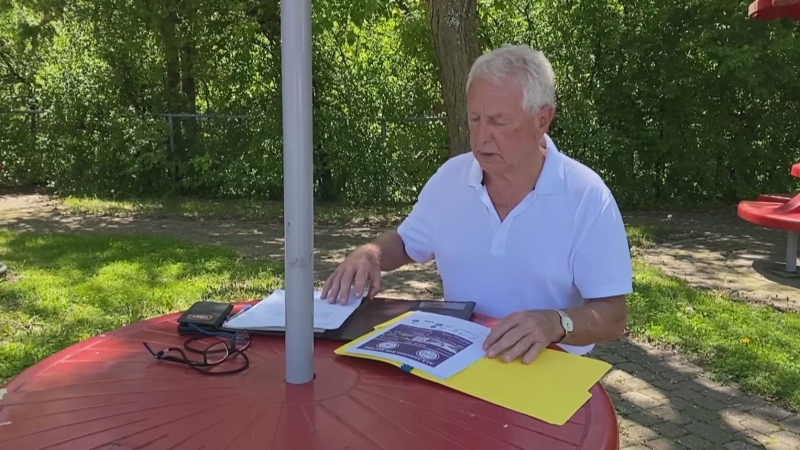

While the surge is likely an unusual blip, it’s a problem that Dr. Shawn Whatley, president of the Ontario Medical Association, says could have been foreseen and prevented.

Ontario has eight Level 3 neonatal intensive care units, or NICUs, and most of them have been struggling with a surge in demand since early August. In the last few weeks, more than half the NICUs in the province have reported being full and closed to new patients.

SickKids Hospital in Toronto, along with Mount Sinai and Sunnybrook, have been particularly hard-hit.

It’s not clear why there have been a surge in premature babies being born in recent weeks, but Dr. Whatley says the real problem is that the hospital system is run in such a way that it just can’t handle unexpected patient surges.

“Overall, the issue is that we run our hospitals so tight and so near 100 per cent capacity all the time, that it’s inevitable that we’re going to end up with a day now and then where there aren’t enough beds for our sick babies,” Dr. Whatley told CTV’s Your Morning Thursday.

Dr. Whatley says hospitals have been forced to scramble to find “creative solutions” to the problem. Some have transferred babies to other NICUs around the province, even when it has meant splitting up newborn twins to ensure they get the care they need.

Others have had to send the babies who really need Level 3 NICU care to Level 2 centres instead. In some cases, hospitals have simply brought in more bassinets, leaving staff to care for many more sick infants than they are trained to handle.

While no babies are being denied care, Dr. Whatley says the system cannot continue the way it is. Longer-term solutions need to be found, he says. As it is, front-line workers are over-stressed and at risk of burnout, and parents are forced to endure more stress than the birth of a premature infant already brings.

“I don’t think this needs to be this way,” Dr. Whatley said.

He says Ontario hospitals have been facing funding cuts for years and that’s what’s leading to the crises we’re witnessing now. In 1990, for example, the province had 33,000 acute care beds. Today, it has 18,400, he says.

“So you can’t keep cutting beds without getting to the point you don’t have enough beds for the sick people who need them,” he said.

Lots of research has been done on how to run hospitals efficiently through “patient flow” and “queuing theory,” but Dr. Whatley says the bottom line is that when hospitals are forced to operate at capacities greater than 85 per cent, “efficiency drops and wait times go up.”

Canada as a whole could be doing better, he adds. The country has one of the lowest number of beds per 1,000 population of any OECD countries – 2.7 beds per 1,000, compared to 8 per 1,000 in Germany, and 13 per 1,000 in Japan.

“So we need to start funding hospitals a little better than we’ve been doing,” he said.

“That’s a start. But ultimately, we need a conversation. We need everybody together to work this out. We can do better.”