As Canadian hospitals remain overwhelmed by a surge in patients with respiratory illnesses, experts say mental health-care systems have been struggling with a jump in demand since the COVID-19 pandemic started. Many Canadians looking for mental health services today are faced with long wait times and a limited number of affordable options, they say, both of which can act as barriers to access.

“There’s definitely a sense that we don’t have enough resources to respond to the need,” Margaret Eaton, national CEO of the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), told CTVNews.ca in a telephone interview. “There’s need, and there’s this gap in being able to actually provide the service.”

According to data collected by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), Canadians are waiting weeks in order to access ongoing mental health counselling in their community. Based on data collected from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021, about half of Canadians waited 22 days, on average, for their first scheduled mental health counselling session. About 10 per cent of Canadians waited nearly four months.

It’s important to note that data collected by the CIHI is incomplete. As of Dec. 8, 2022, there was no data available from Ontario, Quebec, Prince Edward Island or Nunavut.

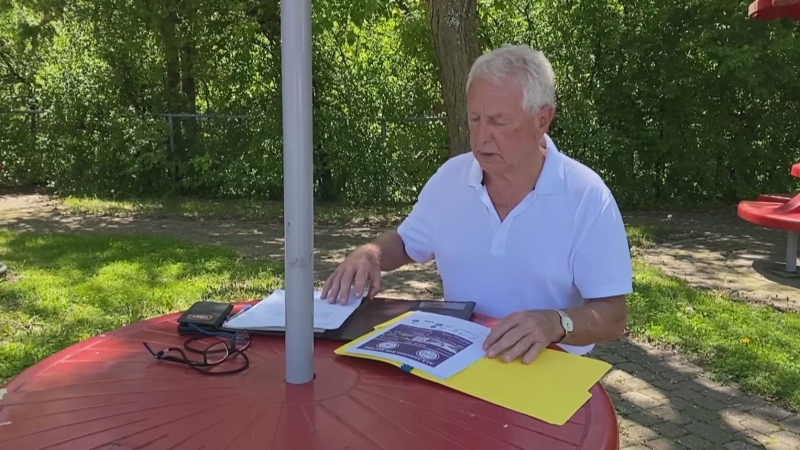

Despite these numbers, some mental health providers have waitlists that are six months to one year long. At the CMHA’s Peel Dufferin branch in Ontario, CEO David Smith says there have been more instances of residents reaching out for mental health support since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The branch, which is partially funded by the provincial government, saw a 30 per cent increase in crisis calls by June 2020 compared to the year before. The branch’s crisis help lines, which are open 24/7, provide an immediate response to those calling in for help, either over the phone or through in-person visits. Since then, the demand for assistance has remained fairly consistent year-over-year, he said.

Prior to 2020, the branch received about 40,000 crisis calls per year but since the pandemic began, that number has increased to nearly 60,000. As of 2022, front-door or non-crisis calls have also risen to about 17,500 to 18,000 per year, compared to about 14,000 calls prior to the pandemic.

“It is alarming,” Smith told CTVNews.ca in a telephone interview. “I would have called [this situation] a crisis for a long period of time.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the branch has made an effort to pivot towards addressing every single call with some level of service upfront, in an attempt to reduce wait times. However, for those in search of ongoing mental health counselling, the wait time is now approximately six months, Smith said.

“It used to be two years for our core case management and multidisciplinary team services,” Smith said.

Just under 100 people remain on the branch’s waitlist for intensive services, Smith said.

‘NO ONE’S ACCEPTING NEW CLIENTS’: B.C. PSYCHOLOGIST

Erika Penner is a Vancouver-based psychologist and co-director of advocacy with the British Columbia Psychological Association. She says it’s “unbelievably difficult” to find a psychologist in the city, particularly one with a private practice, who is able to take on new clients immediately.

“Most psychologists work in the private sector … and I can’t find a psychologist who doesn’t have a six-month to one-year waitlist,” she told CTVNews.ca in a telephone interview. “Everyone has a waitlist, no one’s accepting new clients.”

While the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) says it does not have comprehensive data on this topic, anecdotal reports point to “closed or lengthy wait lists” and “deferred retirement because of the increased demand for psychological care” in Canada.

Penner also points to concerns around the affordability of these services, especially for those with limited coverage through employee health benefit plans.

According to a survey commissioned by the CPA and conducted in 2020, 78 per cent of respondents said the high cost of psychological services in Canada is a very or somewhat significant barrier to access. Additionally, 66 per cent of those polled said another very or somewhat significant hurdle to accessing psychological services is the lack of coverage through their employer’s health benefit plan.

Not being able to afford services was one of the most frequently reported barriers to meeting mental health-care needs among Canadians, based on a Statistics Canada survey released in 2019. Since then, it appears as though self-reported mental health challenges have only increased among Canadians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A report commissioned by the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) and published by Deloitte in November 2021 shows the percentage of Canadians who reported high levels of anxiety peaked at 27 per cent in May 2021, from 20 per cent in April 2020.

Meanwhile, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, high levels of depression self-reported among Canadians peaked at 17 per cent in February 2021. Although data collected in June 2021 shows a decrease in these trends, it remains to be seen whether anxiety and depression levels will go back to what was reported prior to the pandemic.

LACK OF STAFFING A SIGNIFICANT CONCERN

High levels of demand continue to exacerbate the exhaustion felt by therapists and other health-care workers in Canada, Eaton said. A recent survey also highlights the mental health struggles faced by health-care providers themselves.

“A lot of our health-care workers are exhausted, they're burned out from that period during the [beginning of the] pandemic, when they were working overtime to try to meet needs,” Eaton said. “[There are] chronic issues we seem to have in maintaining staff and recruiting staff.”

According to data compiled by CMHA Ontario, the largest issue facing branches across the province is a lack of capacity among its workforce as a result of staff members leaving their jobs. Health and human resources data collected from January to February 2022 shows most resignations among CMHA Ontario branches were associated with stress, burnout and low pay compared to other jobs in the health sector.

“We’re not able to pay people competitive wages so they move on more quickly,” Smith said.

Part of the issue stems from a lack of funding, he said. CMHA’s Peel Dufferin branch has had 142 employees resign since the pandemic began in March 2020.

Experts in provinces such as Newfoundland and Labrador have previously pointed to a shortage of psychologists in the public system, citing many who have entered private practice instead. But according to the Canadian Psychological Association, more comprehensive data is needed to determine whether there is actually a shortage of psychologists in Canada. Little data currently exists on the number of psychologists and psychotherapists in Canada.

STRUGGLES WITH CONNECTING TO OTHERS

A recent study suggests one in eight older Canadian adults experienced depression for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“People who’ve made it to old age and never been depressed before were triggered enough by the pandemic that they developed depression,” co-author Esme Fuller-Thomson, a professor at the University of Toronto, told CTVNews.ca in a telephone interview.

“I knew there was a problem just by observing the whole community [but] I didn’t know the magnitude.”

Shortly after the pandemic began, Eaton said Canadians of all age groups who had never called the CMHA before began reaching out for help. The pandemic has been so harmful to Canadians’ mental health due to its impact on the ability to connect with others, Smith said.

“Our mental health is protected by our relationships with other people,” she said. “We’re social creatures.”

Although COVID-19 physical distancing and isolation measures have largely been lifted throughout Canada, Eaton said she remains concerned about the pandemic’s long-term impacts.

Following the wildfires in Fort McMurray, Alta., in 2016, the CMHA continued to receive calls from residents looking for mental health support years after the event, Eaton said.

“Up to two years after the incidents, people were still experiencing mental health challenges from those extreme events,” Eaton said. “So we expect that there will be the same kind of thing [with COVID-19].”

These concerns are compounded by anxiety many Canadians may be experiencing as a result of high inflation and a rising cost of living, said Smith.

“Many of the folks that use our services are already marginalized and maybe they're on fixed incomes,” he said. “Seeing seven per cent inflation against that [means] they're able to buy less and enjoy it less.”

REPAIRING THE ‘PATCHWORK QUILT’ OF MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

Eaton is calling for the creation of a universal mental health-care system in Canada, as well as greater investment in mental health services by the federal government.

“We’ve got this very broken mental health system … it’s kind of a patchwork quilt where some people can access care, others can’t. Some can afford it, others can't,” she said.

As part of its 2019 platform, the Liberal government announced it would establish a Canada Mental Health Transfer, a new federal transfer involving payments to provinces and territories to fund mental health services. Eaton said the CMHA would like to see this transfer established sooner rather than later.

The CMHA is also calling for a federal mental health act, as well as further investments in housing and income supports as a holistic approach to addressing mental health needs of Canadians, she said.

Penner is also advocating for a more organized mental health-care system within the province of B.C. She hopes to see more co-operation between family doctors and mental health experts such as psychologists as part of collaborative primary care model.

“When we're not sure what's going on, people will go to a family doctor, so let's meet them there,” she said. “People deserve to receive treatment with they need it.”