Multiple provinces are investing in a form of T-cell therapy that could offer hope for cancer patients who are running out of treatment options, according to an Ontario physician.

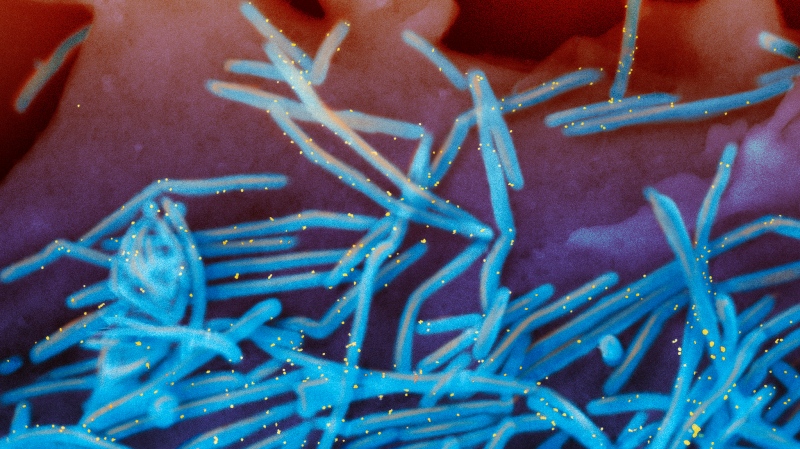

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is a new treatment that targets certain types of blood cancers, specifically forms of leukemia and lymphoma. T-cells are a type of white blood cell that play a role in immune response to illness.

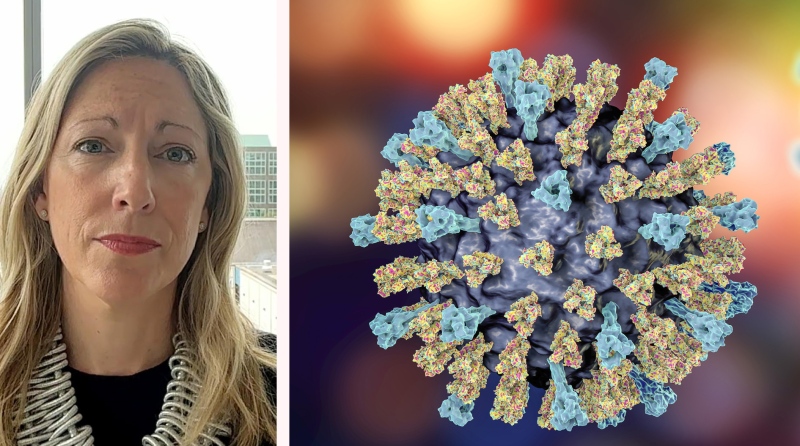

Dr. Natasha Kekre, a hematologist at The Ottawa Hospital, told CTV’s Your Morning Friday that this treatment is the “next wave” of cancer therapies where doctors can take a patient’s immune system, and target it to a specific cancer protein.

“When we take those T-cells out from a patient’s own immune system, we take it to the lab, we re-engineer it, and then we re-infuse it into a patient to really target their own cancer,” she said.

Kekre led the first clinical trial of Canadian-made CAR T-cells in 2019in conjunction with the Ottawa Hospital and BC Cancer and will help lead a national trial starting this year run by the National Research Council, a federal government agency that leads research and development.

The trial was announced Feb. 3 and will begin later in 2023 in Toronto, Vancouver and Ottawa.

In other parts of the country, Manitoba announced in January that it will invest $6.6 million into its own CAR T-cell program, with the aim of launching in the spring. Manitoba physicians described the therapy as “high-quality evidence-based treatment” that can be life-saving, in a press release about the funding published online.

“It really allows for a much more targeted therapy toward their cancer, which is very different than chemotherapy and radiation which is very toxic and a general therapy. This is much more specific to their cancer,” she said.

This type of therapy can target other forms of cancer outside of leukemia and lymphoma, she said. “Hopefully it will target lots of cancers that are difficult to treat.”

From Kekre’s trial that began in 2019, 30 patients have been treated so far and 13 have had “complete responses,” meaning that no more cancer can be detected in their blood. Two others have had partial responses, five have had their cancer progress and nine have died from cancer.

It’s important that the infrastructure for clinical trials continues to be built, she said.

“I hate to see this amazing technology in other countries going into clinical trials, taking five to 10 years to reach market access, and then coming to Canada— that’s just so unfair for our patients,” she said.

She said the National Research Council trial allows physicians to bring new science to patients more quickly.

For more information on the trials and treatment, watch the full interview with Dr. Kekre above.