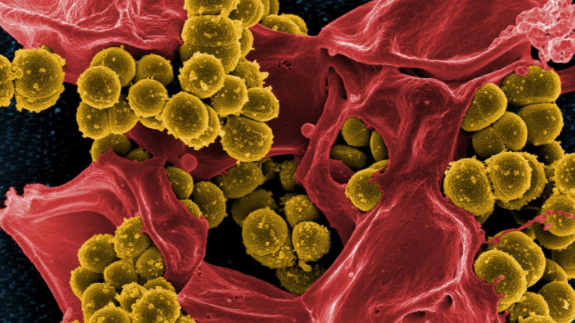

TORONTO -- A new study from an international team at the German Center for Infection Research has determined how the bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis goes from a harmless microbe commonly found on skin -- and morph into dangerous strains that cause what are colloquially known as “staph infections.”

Staph infections can be life-threatening and are difficult to treat as the bacteria are often resistant to antibiotics like methicillin. This makes them highly feared in hospital settings where things like catheters, artificial joints and heart valves can be infection sites.

The study, published Monday in the journal Nature Microbiology, details the research team’s discovery of what distinguishes regular, harmless Staphylococcus Epidermidis (S. epidermidis) and the more dangerous strains.

Researchers identified a new gene cluster than enables the more aggressive Staphylococci bacteria to produce additional structures in their cell walls, which allows the dangerous strains to attach more easily to human cells that make up blood vessels.

In the 2020 Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System Report released by the Public Health Agency of Canada, the data showed that potentially fatal bloodstream infections caused by antimicrobial-resistant organisms (AROs) had increased from 2014 to 2018.

The rate of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, also known as MRSA) blood stream infections increased by 140 per cent -- nearly half of which were associated with injection drug use.

The report said that approximately 20 per cent of patients diagnosed with the ARO blood stream infections died within 30 days of diagnosis.

Between 2015 and 2018, more than 62 Canadian hospitals reported 2,913 cases of MRSA blood stream infections resulting in 555 deaths.

The health organization summarizes the situation in Canada as “getting worse.”

CELL STRUCTURE PLAYS KEY ROLE

The cell walls of Staphylococci bacteria, like other kinds of microbes, are made of teichoic acids, which are chain-like polymers that cover the surface of the bacteria. The chemical makeup of the structures varies from species to species.

In the study, researchers found that the infectious strains of S. epidermidis’ additional gene clusters contained the chemical information to create teichoic acids that are normally found in a more dangerous strain of the bacterium S. aureus.

The study found that if S. epidermidis contained the extra gene clusters with S. aureus information, the microbes were more successful in penetrating the tissues of the human host and therefore became dangerous pathogens.

Researchers also discovered how the bacteria were able to share genetic material despite being different species – a process normally done within the same species with similar structures by bacteriophages, or viruses that infect bacteria.

"Differing cell wall structures normally prevent gene transfer between S. epidermidis and S. aureus,” said researcher Andreas Peschel in a release. “But in S. epidermidis strains that can also produce the wall teichoic acids of S. aureus, that type of gene transfer suddenly becomes possible between different species.”

Peschel and the research believe this information explains how bacteria “pass along” the resistance to antibiotics which makes them so dangerous. The study hopes to continue studying the extra genetic material to better develop vaccinations and treatments against dangerous Staphylococci pathogens.