TORONTO -- A study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases journal has identified a new strain of disease-causing bacteria which explains a rise in infections such as scarlet fever in England and Wales.

Scarlet fever, which most often affects young children with symptoms that include high temperatures, sore throats and a rough pink-to-red rash, is caused by the Streptococcus pyogenes bacterium, known as Strep A.

After a surge of thousands of cases of scarlet fever occurred in England from 2014 to 2016, researchers set out to “identify the Strep A strains causing infection…in England and Wales” by studying the “emm” genes present, the Lancet said in a press release.

“Emm” genes refer to the protein that encodes the surface of a cell to designate it as one of the Streptococcus pyogenes bacterium, according to the CDC.

Researchers hoped that by sequencing the “emm” genes, they could figure out the reason behind the biggest rise in scarlet fever cases since the 1960s.

A particular gene known as “emm1” was designated as the “increasingly dominant” gene in the invasive infections recorded in England and Wales.

This discovery caused researchers to sequence all variations of the “emm1” bacterium and they “uncovered a new strain of Streptococcus pyogenes with an increased capacity to produce scarlet fever toxin.”

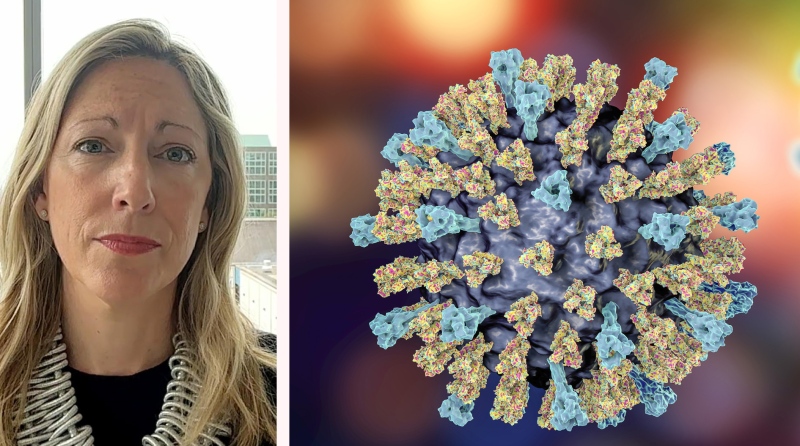

"Given that this strain has an apparently enhanced ability to cause all types of Strep A infection, it is important to monitor the bacterium both here and globally," joint first author Dr. Nicola Lynskey, from Imperial College London, U.K., said in the release.

Researchers found that the new strain of Strep A, dubbed “M1UK” produced “nine times more toxin than other ‘emm1’ strains” and had been present in England as early as 2010.

The study speculates that the recent upswing of Strep A bacterium activity, coinciding with increased cases of scarlet fever “might have provided the conditions required for it to adapt genetically and spread within the U.K.”

Researchers also found strains of M1UK in “emm1” genes in Denmark and the U.S., which they say suggests it has the potential to spread internationally, but say it’s too early to know whether the new strain will be “suited to environments in other countries” due to differences in climate and disease control protocols.