More Canadians are ending their lives with a medically-assisted death, says the third federal annual report on medical assistance in dying (MAID). Data shows that 10,064 people died in 2021 with medical aid, an increase of 32 per cent over 2020.

The report says that 3.3 per cent of all deaths in Canada in 2021 were assisted deaths. On a provincial level, the rate was higher in provinces such as Quebec, at 4.7 per cent, and British Columbia, at 4.8 per cent.

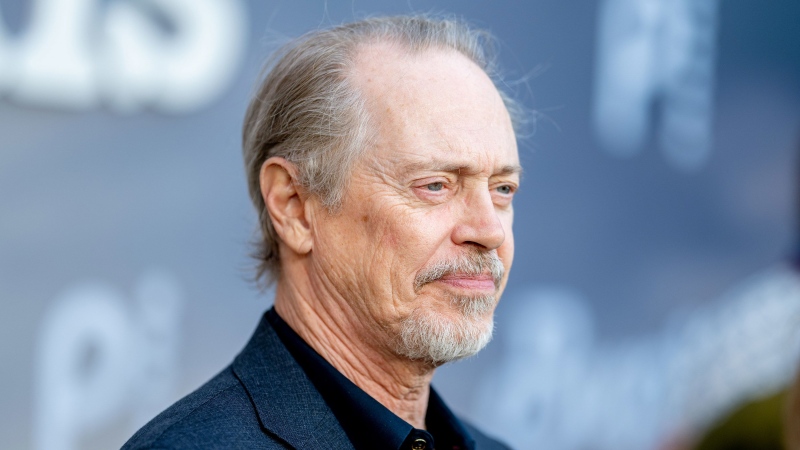

“It is rising remarkably fast," University of Toronto law professor Trudo Lemmens, who was a member of the Council of Canadian Academies Expert Panel on Medical Assistance in Dying, wrote in an email to CTV News. He noted that some regions in the country have quickly matched or surpassed rates in Belgium and the Netherlands, where the practice has been in place for over two decades.

Advocates say it isn't surprising because Canadians are growing more comfortable with MAID and some expect the rising rates may level off.

"The.... expectation has always been it (the rate) will be something around four to five per cent, (as in) Europe. We will probably, in the end, saw off at around the same rate," said Dr. Jean Marmoreo, a family physician and MAID provider in Toronto.

The report uses data collected from files submitted by doctors, nurse practitioners and pharmacists across the country involving written requests for MAID.

Among the findings:

- All provinces saw increases in MAID deaths, ranging from 1.2 per cent (Newfoundland & Labrador) to a high of 4.8 per cent (British Columbia);

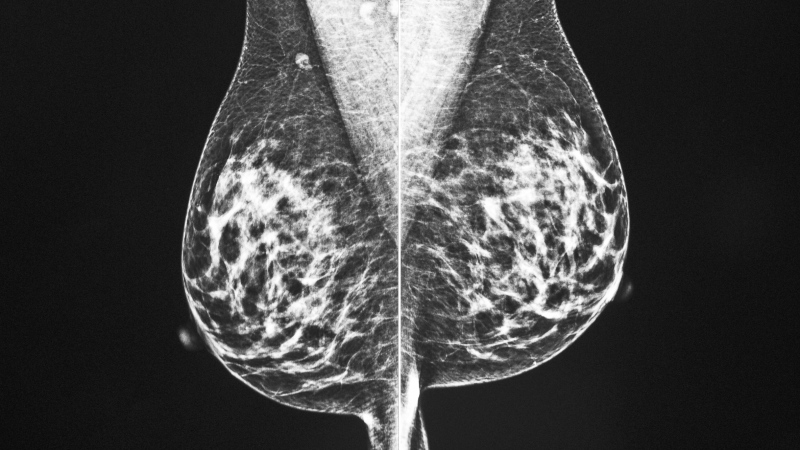

- More men (52.3 per cent) than women (47.7 per cent) received MAID;

- The average age was 76.3 years;

- Sixty-five per cent of those provided with assisted death had cancer. Heart disease or strokes were cited in 19 per cent of cases, followed by chronic lung diseases (12 per cent) and neurological conditions like ALS (12 per cent);

- Just over two per cent of assisted deaths were offered to a newer group of patients: those with chronic illnesses but who were not dying of their condition, with new legislation in 2021 allowing expanded access to MAID.

Documents show that 81 per cent of written applications for MAID were approved.

Thirteen per cent of patients died before MAID could be provided, with almost two per cent withdrawing their application before the procedure was offered.

Four per cent of people who made written applications for medical assistance were rejected. The report says some were deemed ineligible because assessors felt the patient was not voluntarily applying for MAID. The majority of requests were denied because patients were deemed not mentally capable of making the decision.

But other countries with long-established programs reject far more assisted death requests, said Lemmens, citing data that shows 12 to 16 per cent of applicants in the Netherlands are told no.

"It ....may be an indication that restrictions (in my view safeguards) are weaker here than in the most liberal euthanasia regimes,” he wrote in his email to CTV News.

But Marmoreo, who has offered MAID since 2016, sees Canada’s low rejection rate differently.

"It is more like that the right cases are put forward," she said.

"We have a very good screening process right from the get-go. So before people actually even make a formal request to have assisted dying, they have a lot of information that's been given to them by the intake....here's what's involved in seeking an assisted death, you must meet these eligibility criteria."