TORONTO -- Advocates for Canadians suffering from sickle cell disease — a serious condition that can cause crippling pain and frequent hospitalization — are on an uphill battle to create a national registry, something they say could revolutionize the research and care for this oft-neglected disease.

“We would like to have Canadian-based data that we can use in Canada,” Biba Tinga, president of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of Canada (SCDAC), told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

“We need the national registry also to show what better care can look like, to have access to more treatment options.”

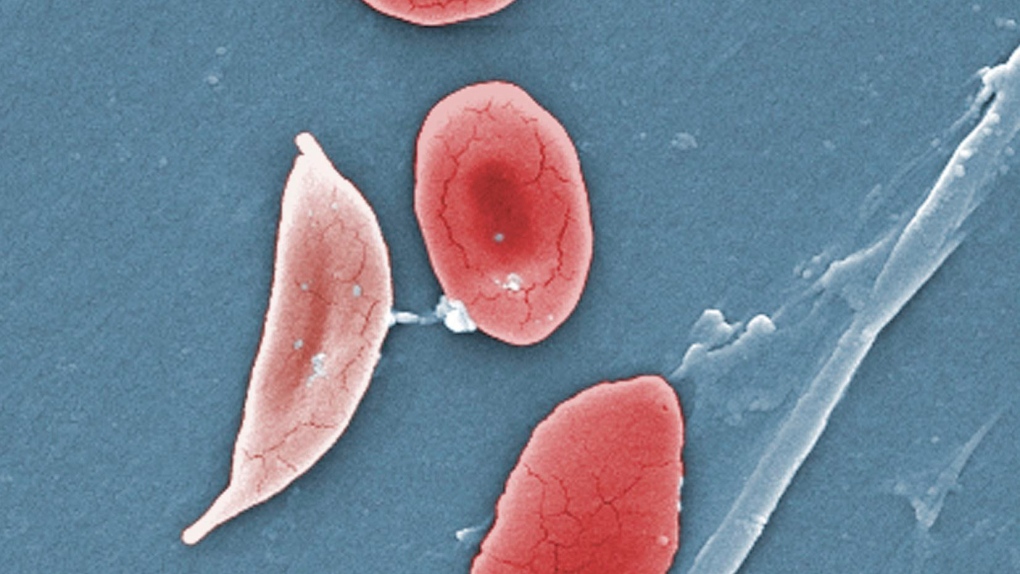

Sickle cell disease refers to a group of blood disorders that are genetically inherited, caused by a person’s blood cells breaking down, or “sickling” into a distorted, crescent shape. These sickled blood cells can cause episodes, or crises, of incredible pain, as well as deprive organs of oxygen, causing organ damage. While some patients may only experience mild symptoms, the disease can send many to the emergency room with pain and risky complications, including stroke, chest pain, high blood pressure, pulmonary hypertension and even heart failure.

It’s a condition that affects thousands of Canadians, but despite the severity of the disease, research and medical support has been scarce, advocates say. Because it is a genetic condition that is found more commonly among those of African, Arabic, and Indian descent, this lack of medical support means a higher burden for these communities.

SCDAC is an umbrella for provincial sickle cell groups in Canada, and they have been pushing for a national registry, which many other serious diseases have, since 2015.

“We need to allocate funds. We need them to just give us the same attention that is given to other disorders,” Tinga said.

The benefits of collecting this kind of data could be huge.

The first advantage would be to have accurate data on just how many Canadians suffer from sickle cell. The numbers that we currently have — around 5,000 Canadians are thought to have the disease — are an estimate based on asking physicians what their patient base is, Tinga said.

But some people may not have gone to a specialist and may have only spoken to their family doctor, leaving those people out of the count.

“Recently, when the COVID-19 vaccine [rollout] started, a young lady called me,” Tinga said. “She said to me […] she has not been to a doctor in years because she hasn't had any crises, but she has this tendency of developing blood clots.”

The woman wanted to know if it was safe for her, as a sickle cell patient, to have the vaccine. Tinga told her that she should get vaccinated, but should ensure she receives the vaccine in a medical setting as opposed to a pop-up so she can receive care if she needs it.

“I took her number and connected her with a provincial [sickle cell] group, but we never knew she was around [before].”

If there was a better count of how many Canadians suffer from sickle cell, and where they are in the country, provincial governments can plan for them, Tinga explained.

“They can be counted and they can be considered in the budget, because at the end of the day, they need to be in the budget to be allocated some resources for their care,” Tinga said. “But if they don't even know how many of them there are then we are left out, right?”

THE PATH TO A REGISTRY

So what could this registry look like? Tinga said they want something that goes beyond a database of information that could be discovered through surveys.

“We want something that can also have a medical component to it,” she said.

“That's why we need to collaborate with the physicians treating these people. And we need to collaborate with the hospitals where they're receiving care.”

The ideal registry, Tinga said, would allow patients — or caregivers and parents, depending on the situation — to log in and provide the registry with information about their medical history and location and demographics in order to have that data. But the registry should also be accessible to physicians, who could log in to add clinical data about patients — what medication is working, what treatments they have been using, etc.

Working with hospitals would also ensure that patients’ personal data was secure and confidential.

“It's not about having access to the data, it's about actually having it there so that physicians, researchers, if they need information — Canadian information — about the patient, about the people in Canada, it's going to be available,” Tinga said. “That's the goal.”

Tinga and the SCDAC aren’t alone in their fight. With the help of a physician at the Ottawa Hospital, they are taking some steps towards what could be the start of a national registry.

Dr. Smita Pakhale is a respirologist and clinician scientist at the Ottawa Hospital, where around 300 people regularly receive treatment for their sickle cell disease.

Her direct specialty is not sickle cell, but because a high number of people with sickle cell have lung issues as well, Pakhale has worked with many of the patients who come to the Ottawa Hospital.

“Because I’m interested in inequity, and sickle cell disease is a disease effecting low-income, racialized minorities predominantly, it’s also my interest,” she told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

Pakhale is attempting to set up a multi-disciplinary clinic for sickle cell at the Ottawa Hospital — a place where a registry could get its footing.

“To create a registry and maintain the registry in a proper way, you need personnel, you need personnel, you need a team, so that data is gathered and data is inputted,” she said. “The registry is as good as the data that is put in it, right? And so we are trying to garner some funding and support from the Ottawa hospital.”

The Ottawa Hospital is currently considering their business proposal to create a mutli-disciplinary clinic for sickle cell at the hospital, she said. They pitched the idea last month, and hope to hear back soon.

If the hospital agrees to create a clinic, it would be the perfect place to launch a registry that could then be expanded nationally.

Tinga pointed out that they would need funding from the government to make the registry a success, not just from individual hospitals.

“Canada needs to put some resources towards that,” she said. “To say, ‘OK, we’re going to set a budget, we’ll have a national registry for sickle cell disease, because this disease affects many Canadians living with it.

“It’s costing the government more money not to do so.”

Many patients delay going to the hospital during a sickle cell crisis because it is a long, expensive trip to the nearest clinic, and by the time they do end up going in, they’re in a worse state than before and may end up hospitalized for a month, Tinga said. If a registry showed where there were a lot of patients, and thus a lot of need, clinics could be built closer to these patients, and hopefully help them receive care faster.

ADDRESSING MEDICAL INEQUITIES

Pakhale pointed out that if we want to learn from COVID-19 and start taking action to undo inequities in society, actively helping a marginalized community such as those going through sickle cell with actual funds and concrete support would be a good step.

“We keep saying Black Lives Matter. We keep saying COVID-19 has uncovered a lot of inequities in our society,” she said. “And we have shown that sickle cell disease affects racialized minorities. But in Ontario, we actually looked at the data and most of our sickle cell patients fall into the lowest quarter [income bracket] so [this] not just affects racialized minorities, it affects low-income racialized minorities.”

She said there is a disproportionately low amount of funding and research into sickle cell in the U.S. as well as Canada.

“We have not received a lot of funding, even though it is a multi-system disease, it is an inherited disease, it's a life-limiting disease and it's a progressive disease,” she said. “And those same characteristics apply to cystic fibrosis, for example, […] and we do have a lot of funding [for that from] the government, but not for the sickle cell.”

More people are thought to be affected by sickle cell in Canada than cystic fibrosis, which affects more than 4,300 Canadians, making the disparity in research and funding more stark.

There has been a national registry for cystic fibrosis since the 1970s.

Sickle cell patients also face stigmatization and racism when they come to the emergency room with pain issues, Pakhale said, often getting labelled as drug seekers and having their pain dismissed.

“This is action that we need to do,” Pakhale said of the registry. “This should have been done many months ago. And this is the right thing to do. So I hope we get the support and funding from the ministry and the hospitals and we can establish the multidisciplinary clinic as well as the national effort on the registry.”

THE GOOD THAT COULD BE DONE

There’s more revealing data that can be discovered from a national registry than just stark numbers about how many sickle cell patients there truly are in Canada.

“From simple demographics to severity of the disease, severity of organ damage, and what kind of treatment they are getting, how they're responding to the treatment — we can learn this all from the registry, if we have proper personnel and ongoing support for the registry,” Pakhale said.

Tinga pointed out that people with sickle cell disease do live longer now than they used to, with many people making it to their 50s or even 60s. But we don’t know much about the quality of life these people have throughout those years.

“Nobody knows that somebody with sickle cell disease can spend months in the hospital and get back [to their] normal life and then lose their job,” she said.

“Most of them are facing the stigmatization of the opioid use. And that is keeping them out of work.”

With a registry that could collect data on quality of life, the data would exist to show where patients need more support, and advocates could present this data to policy makers.

Tinga said this could demonstrate if patients need more psychological support, or provide help for them to get registered as having a disability.

A registry could also provide a quick resource for finding patients to ask if they would like to participate in clinical trials that could bring more drugs to Canada, as there are limited medications for the disease.

“We need to have our own clinical trials here on Canadian patients,” Tinga said.

If patients are aware of clinical trials occurring, they can ask to be part of them, but many people are not aware of new developments in research in order to volunteer. A registry would supply that patient base to run more clinical trials, and it could also be used to compare the effectiveness of various drugs and treatments.

Tinga knows firsthand how helpful a registry like this could be. Her son has sickle cell disease, and when he wanted to go to college, he chose one in Ontario, 10 hours away from where the family lived in Quebec.

At the time Tinga’s son was taking a medication to help with the disease which required him to have monthly visits with a doctor to monitor his progress and check his blood levels. But no physician in the area he was planning to go to school was able to treat him.

“None of them had ever heard about sickle cell,” Tinga said.

Finally, they found a clinic in Sudbury that agreed to run his blood tests every month, and then send the results back to his physician in Quebec for analysis.

“All this could have been done so easy for that physician to log into a registry, see data and be reassured that ‘I can care for these patients,’” Tinga said. “Because they don't have the training, because sickle cell is maybe a chapter in the curriculum in Canada.”

With a registry, a doctor could also locate the nearest clinic that specialized in sickle cell and be reassured that if there were any serious complications, they would know where to send the patient.

The registry could also include information about family members so that people would know if they were carriers and what the chances of having a child with sickle cell might be, Tinga said.

Advocates are hoping that the multi-disciplinary clinic will be approved at the Ottawa Hospital, but even it is, it would still be a while before a registry could get started.

And the journey doesn’t end with one clinic. In order for a national registry to be successful, other regions would need to follow the example set by this first clinic — if it gets off the ground. If other provinces and hospitals have clinics, where dedicated staff can input data into the registry,

“Just creating a national registry at the Ottawa Hospital will not mean anything, unless there are multi-disciplinary centers across the country, which would be feeding data into that registry,” Pakhale said.

“There needs to be ongoing data supplied to that registry, good quality, real-life, real-time data from the clinics who are funded and supported by multi-disciplinary experts, who would then enter data, who would then feed that registry [on] an ongoing basis to create a rich tool for research purposes.”

Tinga said that her message to patients is to “keep fighting.”

But what she wants the government to know is that sickle cell patients in Canada deserve funding and care.

“People who are suffering from sickle cell disease are Canadians,” she said. “They only want a chance [for] a better life, they only want to be able to come and be part of this society and be productive, so let’s work as a community to do that. That’s what we do as Canadians, right?”