Public health experts are sounding the alarm as Canada contends with a record-breaking wave of dangerous, and sometimes deadly, invasive group A streptococcus (strep) infections.

As of Jan. 9, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has received more than 4,600 invasive group A strep samples from 2023, which is the highest annual total ever recorded in Canada and an increase of more than 40 per cent over the previous peak of 3,236 samples in 2019.

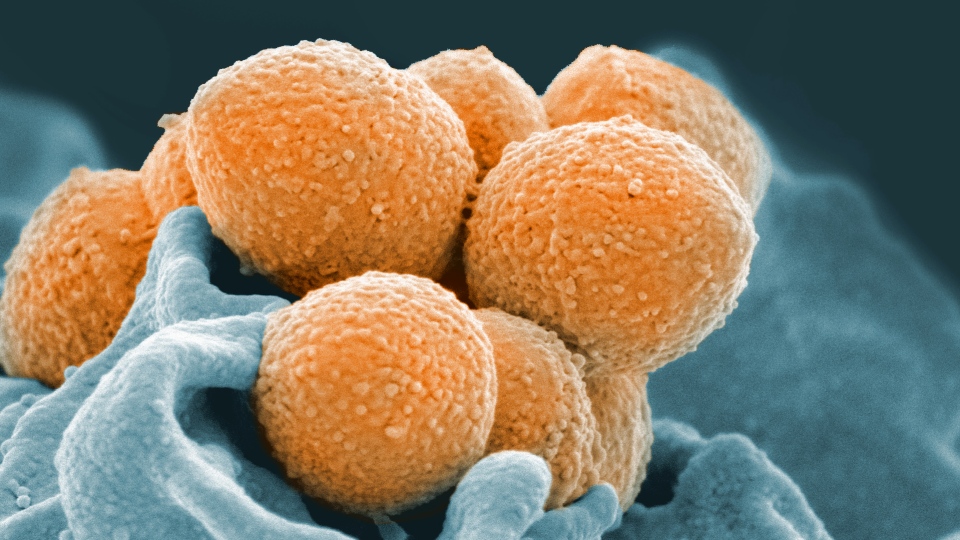

Invasive group A strep, also known as iGAS, is a potentially life-threatening infection involving the normally harmless group A strep bacteria. While a typical group A strep infection often causes mild illnesses such as tonsillitis, strep throat, scarlet fever and a skin infection called cellulitis, the invasive form can cause severe illness and, in rare cases, death within days.

From October 2023 to the end of December, 540 infections were reported in Ontario alone. Around eight per cent of all pediatric cases had a fatal outcome. B.C., Manitoba and New Brunswick have also reported an uptick in cases recently.

Dr. David Fisman, a physician epidemiologist and professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, says cases of invasive group A strep are rare, but often serious.

"This is an uncommon infection but when it does happen it can be devastating," Fisman told CTVNews.ca in an email last year. "We have seen a surge in iGAS in surveillance data, and also many of us who work clinically have seen weirdly severe iGAS."

WHAT IS INVASIVE GROUP A STREP?

Group A strep is a common bacteria that can only survive on and inside humans, explains John McCormick, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Western Ontario.

"It's the same bacteria that lots of kids carry around in their throats asymptomatically without showing any signs of disease," McCormick told CTVNews.ca last year.

Some people who carry group A strep experience no symptoms, while others will become sick with symptoms such as sore throat, fever, headache and abdominal pain, but will recover on their own or with help from an antibiotic. Those types of symptoms occur when the bacteria is present in a part of the body that isn't considered sterile, like the throat or the surface of the skin. It's common for these parts of the body to be exposed to bacteria.

"So once you find (bacteria) in a location that should be sterile, then that's when they call it invasive. And this particular one, when it does that, can get to be very dangerous," McCormick said.

"If it gets into your blood, for example, or if it gets into the soft tissue, or even your muscle – that's necrotizing fasciitis or necrotising myositis – that's very rare but it does happen and it can be very dangerous."

Necrotizing fasciitis is also known as flesh-eating bacteria.

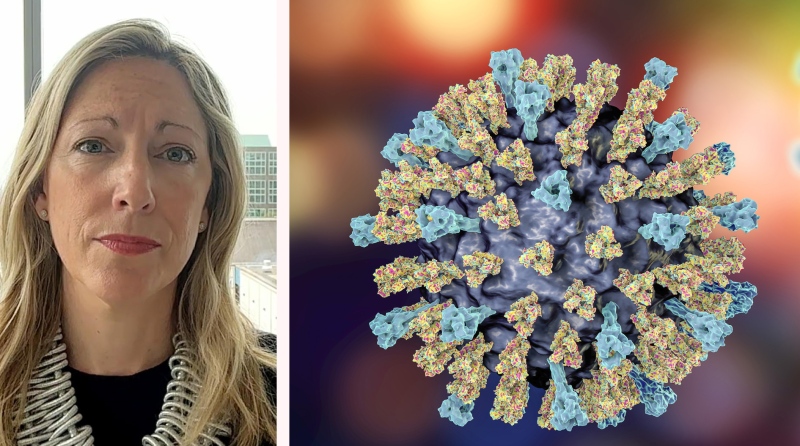

According to Dr. Anna Banerji, a pediatric infectious disease, tropical disease and global health specialist at the University of Toronto, a patient who survives invasive group A strep could also face long-term health issues.

"There can be…post-strep complications that can affect the kidney and affect the heart," Banerji told CTVNews.ca last year.

WHY ARE NUMBERS SPIKING?

According to Banerji, it's probably not a coincidence invasive group A strep infections spiked – along with respiratory viruses like RSV – after many countries lifted the public health restrictions put in place for COVID-19.

"This past year has been a very bad respiratory season, so strep A can be carried in the throat and not have a lot of symptoms, but when you have a cold, that allows the strep to invade," she said.

Like RSV, Banerji explained, many children avoided exposure to strep during the height of the pandemic and wouldn't have the antibodies needed to fight an infection now.

McCormick said there's another popular theory involving a handful of mutant strep A strains, including one named M1UK.

M1UK was first discovered in the U.K. in 2019 and has been linked with spikes in scarlet fever and invasive strep.

"It's got a mutation in it that means it makes a lot of a toxin…and that toxin, we know, could be involved in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, which is a really dangerous form of the invasive disease."

McCormick doesn't know if M1UK or any other mutant strain of group A strep has been linked to any of the cases of invasive strep reported in Canada this year, but he knows some of the strains have made their way here. He's got samples in his lab.

"We know they're in Canada and the United States and other parts of Europe, and so that's probably contributing to the increase," he said.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR CANADIANS?

The rate of invasive group A strep infections in Canada has been creeping upward since 2000, but infections remain uncommon, generally affecting fewer than 10 people per 100,000.

"iGAS does go up and down," Fisman said in an email to CTVNews.ca on Thursday, "but this seems like an unusually big surge, and it's now happened for at least two years in a row.”

Because group A strep is so common and many carriers are asymptomatic, McCormick said it's difficult to avoid exposure.

"I don't think people should be super worried, but I do think they should be aware of some of the symptoms," McCormick said.

Aside from the usual public health best practices – such as practicing good hand hygiene, covering coughs and sneezes and staying home when you're sick – Canadians should know to intervene early when signs of a strep infection appear.

"If they have a child with a severe sore throat or a fever and maybe a rash, then they should go to their family physician and they'll likely be prescribed an antibiotic," he said.

If you’re a parent whose child has recently experienced a bad case of strep, CTVNews.ca wants to hear from you.

Did your child require extra medical attention or did the experience leave you with heightened anxiety? Have you suffered from a case yourself and felt nervous about symptoms getting worse? How did you deal with the experience?

Share your story by emailing us at dotcom@bellmedia.ca with your name, general location and phone number in case we want to follow up. Your comments may be used in a CTVNews.ca story.

With files from CTVNews.ca writer Alexandra Mae Jones and CTVNews.ca writer Daniel Otis

This story was originally published on April 20, 2023 but was updated with new information on Jan. 19, 2024.