A woman in the United Kingdom is being treated for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), a widespread and potentially fatal tick-borne viral disease, after travelling to central Asia.

The disease has been found in dozens of countries since it was first detected nearly 80 years ago and is endemic in some regions, but there has never been a confirmed case in the Americas.

The U.K. Health Security Agency (UKHSA) confirmed the new diagnosis in a statement issued Friday, saying it is in the process of contacting individuals who had close contact with the woman to "assess them as necessary and provide advice."

"[We] have well established and robust infection control procedures for dealing with cases of imported infectious disease and these will be strictly followed," said UKHSA chief medical adviser Dr. Susan Hopkins in the statement.

Hopkins added that CCHF "does not spread easily between people and the overall risk to the public is very low." Two cases were reported in the U.K. in 2012 and 2014, neither of which spread.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CCHF is primarily transmitted to people from tick bites or through contact with infected livestock animals in countries where the disease is endemic.

The WHO says CCHF is endemic in Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East and Asia.

Besides ticks, CCHF hosts include wild and domestic animals, according to the WHO, such as cattle, sheep and goats. Many birds are resistant to infection, but ostriches are susceptible, the UN health agency says.

While the majority of reported cases have occurred in people involved in the livestock industry, the agency warns that human-to-human transmission can occur from close contact with infected individuals through the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids.

CCHF has been detected in over 30 countries, according to Health Canada, with major outbreaks reported in Southeast Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

The WHO reports the disease was first described in Crimea in 1944 and designated Crimean hemorrhagic fever. In 1969 it was recognized that the pathogen causing this was the same as that of an illness identified in 1956 in the Congo, and the linkage of the two places resulted in the virus' current name.

According to a 2021 study published in peer-reviewed scientific journal Microorganisms, there has been no confirmed evidence of CCHF in North America, South America or Australia.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The CCHF virus causes severe viral hemorrhagic fever outbreaks, with a case fatality rate of 10 to 40 per cent, according to the WHO.

Following infection by a tick bite, the WHO says the incubation period of CCHF is usually one to three days, with a maximum of nine days. Following contact with infected blood or tissues of livestock, the incubation period is usually five to six days, with a maximum of 13 days.

According to the WHO, the onset of CCHF symptoms are sudden and include fever, muscle aches, dizziness, neck pain, backache, headache, sore eyes and a sensitivity to light.

The WHO says those infected may also experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain and sore throat early on, as well as sharp mood swings and confusion. Other signs of infection include increased heart rate and enlarged lymph nodes.

After two to four days, an infected person may start to experience sleepiness, depression and a lack of energy. The haemorrhagic phase of the disease typically begins on day four, according to the WHO, with bleeding most commonly manifesting in the stomach, nasal cavity, gums, and urine. A petechial rash, which is caused by excessive bleeding, may also appear inside the mouth, throat and on the skin.

The WHO says severely ill patients may experience rapid kidney deterioration, sudden liver failure or pulmonary failure after the fifth day of illness.

When death occurs, Health Canada reports that it is usually in the second week of illness and is due to "shock brought on by the loss of blood, or by neurological complications, pulmonary haemorrhages, or incurrent infection."

In patients who recover, improvement generally begins on the ninth or tenth day following the onset of symptoms.

TREATMENT

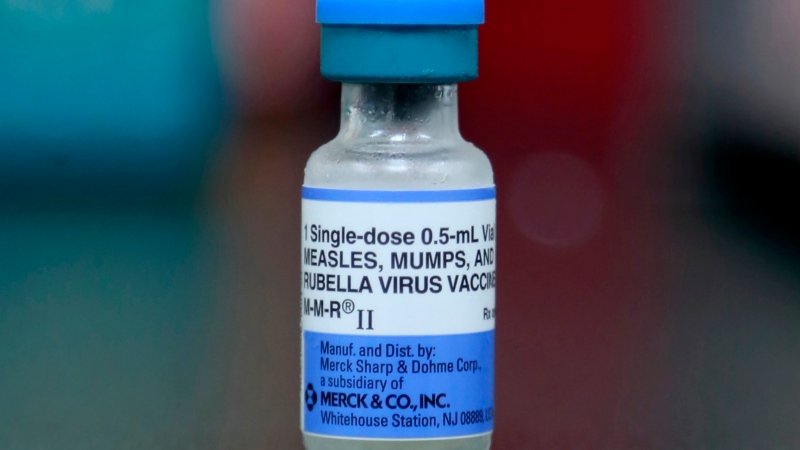

There is currently no vaccine available for CCHF for either people or animals.

According to the WHO, "general supportive care with treatment of symptoms" is the main approach to managing CCHF.

The WHO says the antiviral drug ribavirin has been used to treat CCHF infection to some success, and both oral and intravenous formulations have shown to be effective.

For patients without hemorrhagic complications, Health Canada says treatment with painkillers and fever-reducing medications have proved useful.

PREVENTION

With no vaccine, the WHO says the "only way" to reduce infection of CCHF in people is by raising awareness of the risk factors and provide education on measures they can take to reduce exposure.

If in one of the endemic countries and in an area where ticks may be present, the WHO advises wearing light-coloured protective clothing, such as long sleeve shirts and pants, to help prevent bites and allow easy detection of ticks.

The WHO also recommends using approved acaricides -- chemicals intended to kill ticks -- on clothing and repellent on skin, and avoid areas that have an abundance of ticks, especially during seasons when they are most active.

To reduce CCHF risk via animal transmission, the WHO advises those handling livestock in endemic areas to wear gloves and other protective clothing, especially during slaughtering, butchering and culling procedures.

The WHO also recommends those working in the industry in endemic areas quarantine animals before they enter slaughterhouses or routinely treat them with pesticides two weeks prior to slaughter.