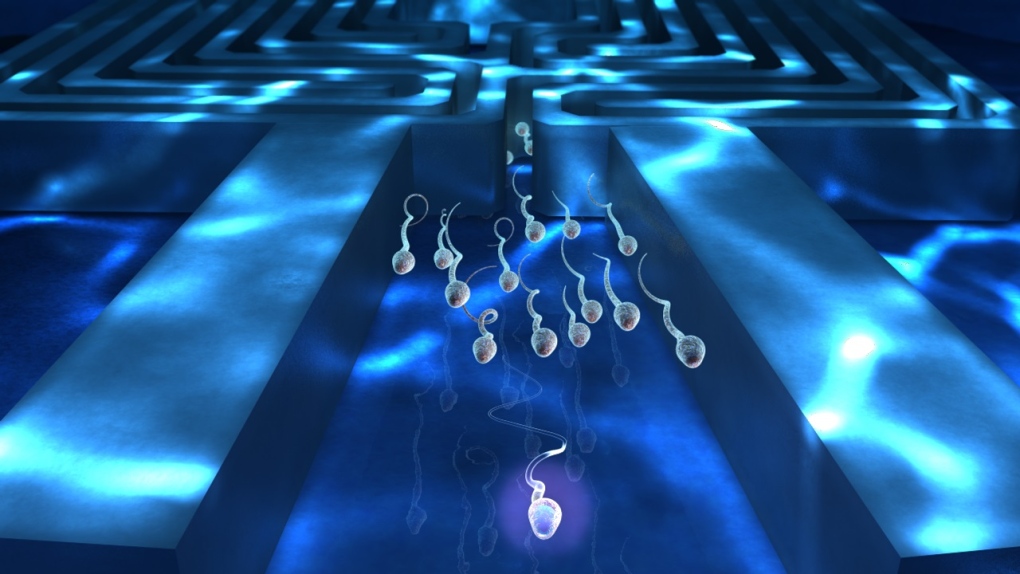

A group of Canadian scientists are perfecting a microscopic ‘sperm obstacle course’ to help doctors select the finest specimen for in-vitro fertilization.

At a recent conference, David Sinton and his team at the University of Toronto’s Sinton Lab outlined the technology, which could eventually be used to help boost pregnancy rates.

Sinton told CTVNews.ca that the new technology expands a well-established science that “guys that make it up stream are better than guys that don’t.”

The team developed the device that hosts a microscopic competition between 100,000,000 sperm. When inserted into the microchip device, the swimmers go through a kind of “regional qualifiers” obstacle course to narrow the field down to 1,000. Instead of allowing the sperm to swim freely in a “corkscrew” motion without boundaries, the device requires the sperm to navigate a two-dimensional plane.

Sinton likened it to modifying the hallway of a house: “Instead of making it three-feet wide, make it a foot wide. Then we’re all going to have to turn sideways and walk down this hallway,” he said.

But sperm are naturally able to swim in a different way, in a slithering motion instead of the typical corkscrew motion. “Sperm are not swimmers the way we understood them to be,” said Tom Hannam, director of Hannam Fertility Centre in Toronto and a partner in the research at Sinton labs. “They slither. They like to go around corners. That’s what a fallopian tube is.”

Sperm are particularly adept at slithering when they want to power through confinement or an area of thick fluid, much as they do through fallopian tube, he said. The new technology is a solution that mimics nature more closely.

The stronger the sperm, the more likely they are to make it to the finals of the microchip competition. The results have been promising, said Sinton. “The device seems to be collecting a few really good ones from samples that, on average, are not great,” he said.

That’s the key to the research as fertility has been dropping among men since the early 20th century, according to recent studies that showed a 50 per cent global reduction in sperm quality over the last 80 years. A new study out of the U.K., published Tuesday in Scientific Reports, suggests that environmental contaminants found in the home and diet may be affecting the quality of sperm in men. As a result, more couples are seeking IVF procedures to help conceive a child.

Sperm selection is typically done with the eye. Doctors look for the fastest, most agile of the sperm. Often these methods involve “spinning tests” to assess the agility of the sperm. But those tests can damage the DNA in the head of the sperm, which could lead to a less viable embryo.

“For all the successes we’ve enjoyed (in fertility science), we haven’t actually advanced things on the sperm side,” said Hannam.

Advancements to select the best of a bad bunch have been few until research like that from Sinton’s team. But there is still more work to be done. After the initial “regional qualifiers” round, Sinton’s team hopes to develop technology that will use image-based analysis to further assist in identifying the best sperm for IVF.