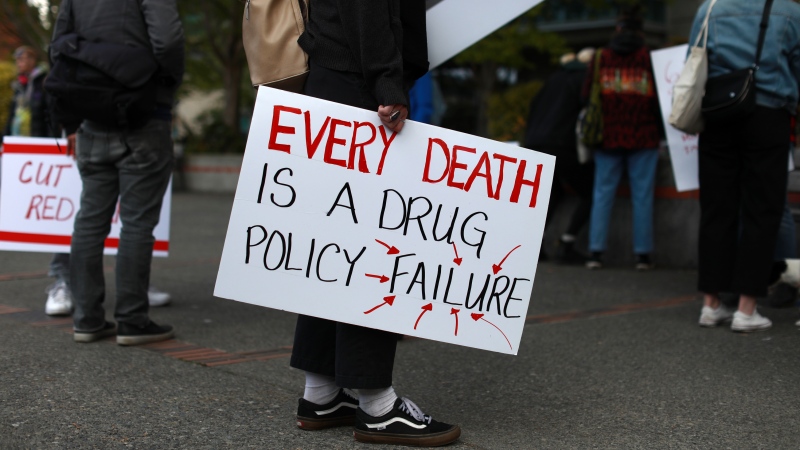

Not all calories are digested equally, and those that come from a simple carbohydrate derived from fruits and vegetables -- called fructose -- could lead to weight gain at a greater rate than calories from other sources, according to a new study.

Fructose has woven its way into the food industry to the point of becoming nearly a staple, and when the research team did a calorie-for-calorie comparison of fructose and the simple sugar glucose, they concluded that the effects of the latter are softer.

"Given the dramatic increase in obesity among young people and the severe negative effects that this can have on health throughout one's life, it is important to consider what foods are providing our calories," says research director Justin Rhodes.

In the study, the researchers worked with two groups of mice for two-and-half months.

One group was fed a diet in which 18 per cent of the calories came from fructose -- for contrast, teenage boys in the US are thought to get 15 to 23 per cent of their daily calories from fructose.

The other group of mice was fed a diet in which 18 per cent of their calories came from glucose.

"The important thing to note is that animals in both experimental groups had the usual intake of calories for a mouse," says lead author Catarina Rendeiro, a postdoctoral research affiliate at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

Calorie-wise, the diets were in the normal range for mice and since both groups ate the same proportion of calories from sugar, the only difference was what kind of sugar they were eating, says Rendeiro.

Researchers observed that the fructose-fed mice got lazy, gained weight and fat mass significantly more than the glucose-fed mice.

"We know that contrary to glucose, fructose bypasses certain metabolic steps that result in an increase in fat formation, especially in adipose tissue and liver," he says.

The paper was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

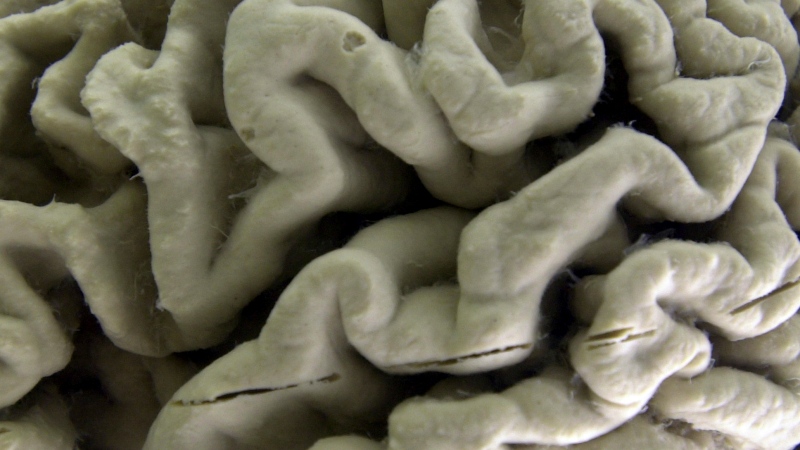

Another recent study suggests that the brain may respond differently to glucose and fructose.

Those researchers, who presented their work at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting in December, found that fructose intensified the feeling of reward that comes from the brain, which eventually makes you want more food.

Eating fructose reduces satiety hormones, preventing you from feeling full after eating, the research indicated.

Working with 24 young men and women from 16 to 25 years of age, the research team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study their reactions to seeing pictures of tempting treats like chocolate cake.

They were tested in this manner after drinking a fructose-sweetened beverage and after drinking a glucose-sweetened beverage and the former produced more hunger and motivation to eat, according to the study.