TORONTO -- A new study suggests that exposure to the bubonic plague may have had a long-term effect on human immunity genes.

Scientists examined the remains of 36 bubonic plague victims from a 16th century mass grave in Germany and found evidence that "evolutionary adaptive processes driven by the disease" may have increased immunity for later generations of those in the region.

"We found that innate immune markers increased in frequency in modern people from the town compared to plague victims," the study's senior author and University of Colorado associate professor Paul Norman said in a press release.

"This suggests these markers might have evolved to resist the plague," he added.

The study was conducted by researchers out of the University of Colorado, in conjunction with the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

The findings were published Tuesday in Oxford University Press' peer-reviewed medical journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

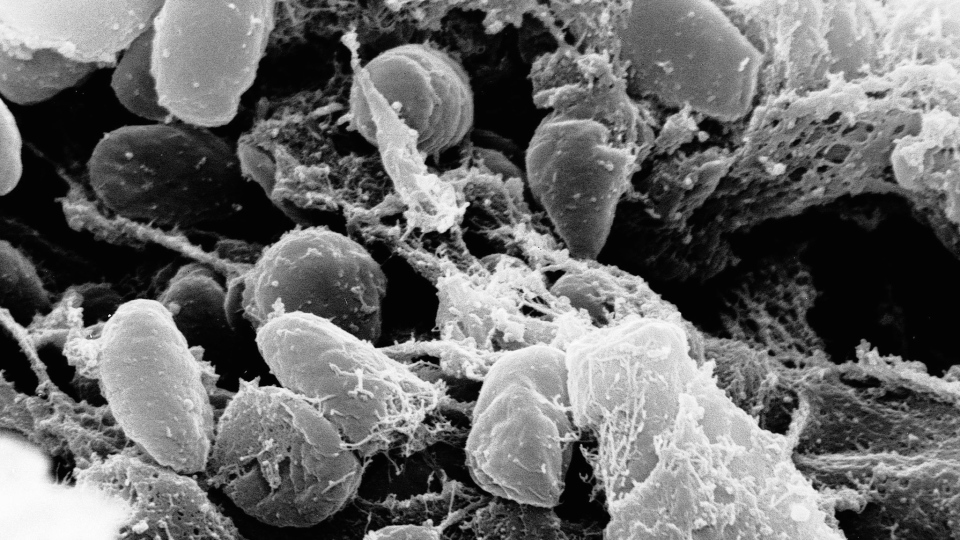

The bubonic plague was one of the deadliest bacterial infections in human history, causing an estimated 50 million deaths in Europe during the Middle Ages when it was known as the Black Death.

The rare disease, which is now treatable with antibiotics, is still around today with cases having been recently reported in China, Mongolia and the U.S.

To understand how immunity develops over time, researchers collected DNA samples from the inner ear bones of plague victims from the southern German city of Ellwangen, which suffered outbreaks in the 16th and 17th centuries.

They also took DNA samples from 50 current residents of the town.

The researchers compared the samples' gene variants to a large panel of immunity-related genes.

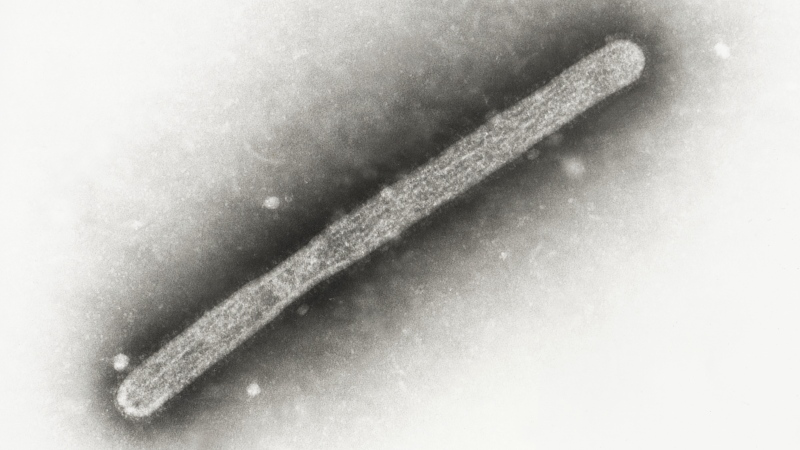

Researchers found that a pathogen, likely the bubonic plague-causing Yersinia pestis, prompted changes in the gene structure of two innate pattern-recognition receptors and four Human Leukocyte Antigen molecules.

According to the study, these receptors and molecules "help initiate and direct immune response to infection."

"We propose that these frequency changes could have resulted from Y.pestis plague exposure during the 16th century," Norman said in the release.

Researchers say the findings are the first evidence that evolutionary processes prompted by the Yersinia pestis bacteria may have "shaped certain human immunity-relevant genes in Ellwangen and possibly throughout Europe for generations."

Since Europe battled the plague for years, the study suggests that these immunity genes may have been "pre-selected in the population long ago," but have recently gained attention because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Although the lethality of the plague is very high without treatment it remains likely that specific individuals are protected from, or more susceptible to, severe disease through polymorphism in the determinants of natural immunity," the study said.

"In this case, any change in allele frequencies that occurred during a given epidemic crisis could be evident as genetic adaptation and detectable in modern day individuals."

Norman noted in the release that natural selection likely drove these gene changes in future generations.

"I think this study shows that we can focus on these same families of genes in looking at immunity in modern pandemics," Norman said. "We know these genes were heavily involved in driving resistance to infections."

He said the new findings also demonstrated that, regardless of how bad a virus outbreak gets, there will "always" be individuals who are less prone to the severity of infections because of their genetic structures.

Despite the Black Death being the most fatal pandemic recorded, the study noted that two-thirds of Europeans survived.

"It sheds light on our own evolution," Norman said. "There will always be people who have some resistance. They just don't get sick and die and the human population bounces back."

However, Norman says individuals should not rely on their body’s own immunity to fight COVID-19, and should get vaccinated when eligible.

"I wouldn't want to discourage anyone from taking a vaccine for the current pandemic. It's a much safer bet than counting on your genes to save you," Norman said.